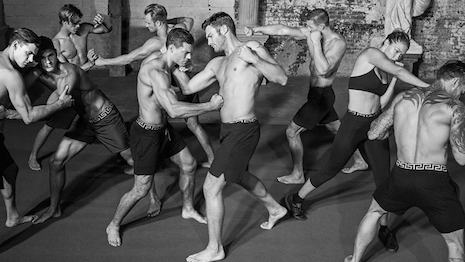

Putting up a good fight: Versace's Dylan Blue Pour Homme. Image credit: Versace

Putting up a good fight: Versace's Dylan Blue Pour Homme. Image credit: Versace

By Pamela N. Danziger When the news broke that Michael Kors Holdings paid $2.12 billion for Italian fashion brand Gianni Versace S.p.A., people were surprised at the price. Calling the offer “a rich one,” The Wall Street Journal reported the brand had generated only $17.5 million in profits last year. Oliver Chen, managing director for consumer research focused on retailing/department stores, specialty softlines and luxury at Cowen, was more bullish about the deal. With estimated sales of $775 million in 2018 and expectations to reach an ambitious $850 million in 2019, Mr. Chen put the enterprise value on Versace at 2.5x and EBITDA around 13.9x, which on both counts are within the luxury sector averages for acquisitions since 2011. Along with the Versace news, Kors also announced it will change its name to Capri Holdings Limited, upon closing the deal in the fourth quarter, after the famed Italian island “long recognized as an iconic, glamorous and luxury destination,” the press release stated. This is the second of Kors major luxury acquisitions, following Jimmy Choo for $1.2 billion last year. At the time, Kors CEO John Idol told CNBC that “this will not be [Michael Kors’] last acquisition.” Mr. Idol said, “Acquiring Jimmy Choo is the beginning of a strategy that we have for building a luxury group that is really focused on international fashion brands.” Now, he is keeping that promise. As a result, obvious comparisons to global luxury-leading conglomerate LVMH come to mind. With Versace’s management team of creative head Donatella Versace and CEO Jonathan Akeroyd continuing to lead, and likewise at Jimmy Choo, the Kors vision of collecting a family of luxury brands was described by Greg Furman, founder and chairman of the Luxury Marketing Council, as “LVMH-izing American luxury.” LVMH does it better In its first two acquisitions, Kors signals outsized ambitions, but can it really go the distance? “There is not even a remote comparison to the dominant powerhouse of LVMH, which has consistently outpaced the market in sales trend, profits and shareholder value,” said Fashion Institute of Technology’s Shelley Kohan. “Three brands a luxury conglomerate does not make,” she said. Pointing to the long track record of LVMH’s success, Ms. Kohan emphasizes its clear, strategic focus across 70 brands and six business segments that gives each business the autonomy to make decisions best suited for the individual brands. Kors does not have that luxury, she said. “Capri will not have the same power of aligning the strategic direction and giving brands carte blanche to run their own divisions as each of the three brands come to the table with significant flaws,” Ms. Kohan said. Regarding Versace, Erich Joachimsthaler, founder/CEO of Vivaldi, a global brand strategy consulting firm, says LVMH and other European conglomerates Richemont and Kering eyed the opportunity and passed. “There is much more value in Versace for Kors than the others, which explains why Kors paid such a premium,” Mr. Joachimsthaler said. “The acquisition logic makes sense, but there are enormous risks,” he said. “Cost efficiencies will be minimal, which is normally how companies justify a price premium in acquisitions, and hence short-term, this deal is difficult to justify.”

Introducing the fall/winter 2018 Jimmy Choo collection

Making over Versace in Michael Kors’ fashion Prominently missing in the Kors acquisition announcement of Versace was any mention of cost-saving synergies that it will realize. Quite the opposite: the company will have to invest significantly to get Versace on track, including expanding its retail presence from 200 stores to 300 stores and building its ecommerce and omnichannel capabilities. While there is hope Versace can piggyback on Kors’ highly effective online and social media strategies, it is way behind Michael Kors on that score. SimilarWeb reports that in the past 12 months michaelkors.com averaged ~890,000 visits from U.S. consumers, compared with only 170,000 monthly visits to versace.com. Further, United States site visitors were nearly twice as engaged on michaelkors.com than versace.com, spending nearly 6 minutes and visiting 9 pages on the former and only about 3 minutes and visiting 5 pages on the latter. SimilarWeb did note that millennials ages 18-24 were Versace’s biggest traffic draw, but then lookers do not make buyers, and in that realm Versace’s existing luxury price points are a big deterrent. Kors hopes to have a fix for that by shifting Versace’s business from clothing-centric to what is generally considered more affordable, fashion accessories, which is Kors’ sweet spot. It plans to grow Versace’s men’s and women’s accessories and footwear from 35 percent of revenues to a whopping 60 percent. This is more in line with what Kors does, with accessories accounting for 65 percent of revenue in 2018 and footwear 14 percent after the addition of Jimmy Choo. This strategy would suggest that Versace will move more down-market playing off its Medusa and Greek key logo icons to accessorize handbags and shoes. But that might jeopardize the alternative view that the Versace acquisition was intended to move Kors more upmarket where LVMH lives. “The Versace acquisition helps Kors anchor at the higher end,” Mr. Joachimsthaler said, “which is important for Kors. As a quintessential American brand, it has moved more toward mass and away from luxury in its accessories line. “Jimmy Choo and, now Versace, if managed correctly, will help move the needle in that perception,” he said. Mr. Joachimsthaler also notes that it is harder for a company such as Kors to scale vertically. “This strategy is highly risky, though the market conditions are favorable now,” he said. “What if the economy turns, which is likely to happen in the next two years?” A lot depends on the ability of the powerful brand leaders that Kors now has in place to synergize its brands’ strengths and develop complementary systems to shore up weaknesses. “Companies in a quest to create global dominance will have varied views on direction that should be taken,” Ms. Kohan said. “Culture and leadership must be considered when brands merge and the people of the businesses can make or break the model, regardless how well it’s built.” That makes me question whether Italian-based luxury royalty such as Donatella Versace will readily take marching orders from American upstarts such as Mr. Kors and Mr. Idol, whose resume includes leadership with Donna Karan and Ralph Lauren prior to joining Kors in 2003. Versace's in the bag. Image credit: Michael Kors

Versace's in the bag. Image credit: Michael Kors

The Clans of Versace: Fall/winter 2018 ad campaign

Time for an American-style new luxury business model As for me, I think Kors is following a more “Traditional Luxury” – dare I say “Old Luxury” – path whose time has passed. LVMH has nailed it, dominates it and will aggressively defend it. There is only so much “Traditional Luxury” to go around and I fear an increasingly shrinking market for traditional luxury goods, as millennials move into their prime and favor spending on experiences. Rather than build a traditional luxury brand conglomerate in LVMH fashion, I think the bigger opportunity is to envision what a family of new luxury brands could bring to the market. Traditional luxury is based upon a history and heritage born in Europe with an inbred aristocracy and a class structure that is diametrically opposed to the American way. THE TIME IS right for innovation in a luxury business model that reflects the vibrancy, dynamism and democratic approaches that a uniquely American perspective could bring. Ironically, Walmart seems to be trying to do just that. “The Europeans understand the importance of craft, sophistication and aesthetic in the luxury market, but Americans have the edge in understanding the new ways luxury consumers want to connect with brands,” Mr. Furman says. “Americans will do it better,” he said. I am afraid that Kors has not figured that out yet. Instead, it is following an old, traditional luxury model that I am skeptical will carry it too far into the future. Pam Danziger is president of Unity Marketing

Pam Danziger is president of Unity Marketing