The COVID-19 coronavirus outbreak has shook the underpinnings of the modern aspiration economy

The COVID-19 coronavirus outbreak has shook the underpinnings of the modern aspiration economy

By Ana Andjelic

A few months ago, the second biggest air travel story was Qantas’ first 19-hour direct flight from New York to Sydney. The first story was about the woman who reportedly reclined her seat too far.

Fast forward, and air travel is at standstill.

Getting on any plane, full-reclined seat in front us and all, feels like a fond memory.

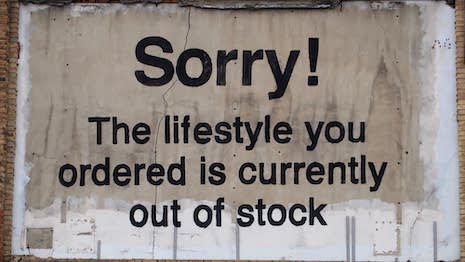

The COVID-19 coronavirus is perhaps a fitting crisis for the modern aspiration economy. With uncanny precision, it targets all its tenets: travel, tourism, dining, experiences, leisure, art and culture, and the luxury business.

In less than two months, it exposed the vulnerabilities of trading in social, cultural and environmental capital.

“Access over ownership” and “experiences over possessions” make great sense if there is access and experiences to be had.

Once New York galleries, theaters, restaurants, fitness centers and nightclubs closed, and all the rich fled to the Hamptons, the city’s social, cultural and environmental capital went to zero.

Having a spacious apartment and a nice furniture counts more in the days of Zoom.

Along with intangibles such as access, experiences and knowledge, the modern aspiration economy also created a cultural class unto its own.

Oriented towards wellness and self-perfecting, this class of self-proclaimed “creatives” – regardless of what they actually do – defies the hierarchy that socially bound previous generations to their economic standing, and lives the lifestyle of the affluent without actually owning the assets to underpin it such as a home or a savings account.

This consumer class also created a signature aesthetic genre, a number of taste regimes and an entire direct-to-consumer economy of lifestyle add-ons.

These aspirational consumers now realize two things: the chances of perfecting oneself are much better when a person is not shut in 700 square feet, and sharing lifestyle add-ons of the rich does not make one rich. Buying a coronavirus test, booking a COVID-19 service in a Switzerland, and having 3M N95 mask does.

The rich belong to the old industrial economy and to the traditional luxury. They own objects that signify stability, security and durability, such as real estate, hard luxury, antiques, high-end wine and collectible art.

The core promise of hard luxury is its permanence – the tag line says it best: “You never really own Patek Philippe. You merely look after it for the next generation” – and its liquid and increasing asset value.

For example, consider a spike in investment in “survival” real estate dating back to 2017.

According to Steve Huffman, cofounder of Reddit, as many as 50 percent of Silicon Valley billionaires bought a luxury bunker or a getaway island.

Peter Thiel allegedly owns a remote part of New Zealand. When a global pandemic hits, having a remote island is handy.

The coronavirus crisis puts in sharp focus the old-school economic inequality. It also exposes the brand strategy that obscured it.

A decade or so ago, brands shifted from increasing the value of their products through utility, competitive comparison and creative advertising to endowing them with aesthetic, sustainability credentials, a story of artisanship and provenance, and a community to give their products identity and singularity.

An entire market emerged around brands that defy mass production of common industrial products by putting forward items that are meant to be perceived as different.

Modern brand strategy focuses on the sociology of things, not people: it asks how to create social markers of differentiation and dominance around products they sell.

The outcome is that products are valued on their story, design and aesthetics: the dreaded millennial pink, environmental creds as a go-to PR pitch and “locally made” as the brand promise.

This strategic approach shifted dynamics of the capitalist system from making products that have been outsourced to China towards enhancing objects with social, cultural and environmental value.

When a global pandemic jeopardizes production of social, cultural and environmental value, it jeopardizes the entire economy organized around it.

Most affected are countries with economies organized around making and exporting high-end goods and services, such as food, craftsmanship, tourism, art foundations and fashion. An economy that revolves around lifestyle add-ons makes an easy target for global crises.

The present near-collapse of the modern aspiration economy accelerates its own future.

Value that the creative class puts on perfecting themselves and their own lives shifts only in form. Scroll down Instagram, and even the global pandemic has, in the hands of creatives, become a tool of self-advancement.

Unlike Veganuary, fasting, Marie Kondo or meatless Monday, quarantine is neither self-invented nor self-imposed. This did not prevent it from somehow becoming self-improving. Restraint has become ethically and socially aspirational.

Aspiration is a narrative: it is the stories we buy into and the products and experiences we buy to be part of these stories.

Once upon a time, American culture symbolized individualism, independence and freedom through iconography of wide plains, open roads and windswept hair.

The narrative that is shaping right now is the one of redemption by restraint. Journalists, public intellectuals and Cory Booker claim that a better world will come out of our hardship.

Famed trend forecaster Li Edelkoort even went as far as to insensitively announce that we should be “very grateful for the virus because it might be the reason we survive as a species.”

We have to believe in silver linings because the alternative is dispiriting.

No one wants to come across as self-centered, spoiled and opportunistic – well, almost no one. So we redeem ourselves by swiftly changing how we present ourselves to the world – “Stay at home,” says every Instagram influencer from his or her own palatial digs.

This shift in presentation is not trivial: it changes how we behave, and our new behavior exerts peer pressure in our social networks, creating a ripple effect.

Most importantly, our new behavior changes our self-perception: we start to see ourselves as selfless, responsible and kind.

In this crisis, the creative class, not the billionaires, leads the way. They are ready to socially shame displays of greed, selfishness and irresponsibility.

The same dynamic applies to brands.

Brands feel the same peer pressure to change their behavior. If LEGO donates $50 million to Education Cannot Wait, others will follow.

If notorious Italian winery Santa Margherita gives a dollar for each view of its video campaign, others will copy.

If Four Seasons provides free rooms to New York coronavirus doctors, others will do the same. Of course, there’s always someone who fails to read the room.

Behavioral change leads to a change in the brand self-perception. A crisis accelerates it.

This is a socially responsible equivalent of millennial pink. Mechanisms of social imitation and self-perception that created a recognizable direct-to-consumer aesthetic, everyday taste regimes and differentiation based on product singularity are also able to make obsolete the economic, social and political system that has proved inadequate to deal with our global crisis.

There are three targets:

Economic. De-growth as an economic aspiration has, until now, been limited to the domain of scenario planning and conference agendas.

After the crisis, the wealth of a country may be understood not only in terms of GDP, but in robustness of its health system and its infrastructure to address a global pandemic and other catastrophic events.

The pressure is already mounting on companies to go beyond pure shareholder value. Efficiency was considered a desirable business goal until it collapsed, exposing its fragility.

Social. People are not only individuals, but they also belong to communities and are members of a society. Their behavior is shaped by those around them and by collective symbols and stories.

The new target unit for brands is a community and a society, not an individual.

Modern brand strategy aims to address not just “jobs to be done,” but jobs to be done in a community and jobs to be done in a society.

“Not for you. For Everyone,” says Telfar Clemens. “Beauty for All,” says Rihanna, who also donated safety gear to New York hospitals.

All brands have to add responsibility, generosity, and social improvement to both their products and their actions.

Political. From who gets to be tested and who gets a protective gear, to social distancing becoming a signal of which side one is on, the coronavirus is a political motherlode. It makes inequality, exclusion and unfairness blatantly obvious. It makes equally obvious the need to address and solve these issues.

The future of the modern aspiration has very little to do with luxury, even in its contemporary iteration of conspicuous production and inconspicuous consumption. This is a good thing.

An aspiration that revolves around community, generosity and social improvement makes our economy, society and politics much harder to disrupt by global crises. Crises will be plenty, but we should all aspire to act in ways that quickly contain them.

Ana Andjelic

Ana Andjelic

Named to Forbes CMO Next, Ana Andjelic is a strategy executive and doctor of sociology. She runs a weekly newsletter, The Sociology of Business, and is author of The Business of Aspiration, out from Taylor & Francis in the fall, available for pre-order here. Reach her at [email protected].