Tracing the source of organic cotton to the farm and through its journey across the supply chain will enhance Kering's sustainability credentials with end-consumers. Image credit: Kering

By Anna Granskog, Franck Laizet, Miriam Lobis and Corinne Sawers

It is time for the apparel industry to radically reduce its contribution to biodiversity loss, argues McKinsey & Co.

That message is resonating with luxury groups such as LVMH, Kering and Richemont, which now have established protocols for a sustainable future.

However, McKinsey suggests the pace should accelerate across the entire apparel business.

The management consultancy, in a piece authored by Anna Granskog, Franck Laizet, Miriam Lobis and Corinne Sawers, outlined four interventions that can make the biggest impact to turn fashion more sustainable. Here is what they had to say:

Even amid the COVID-19 pandemic, sustainability remains top of mind for consumers, investors, and regulators—in fact, engagement in sustainability has deepened during the crisis. For example, two-thirds of apparel shoppers say that limiting impact on climate change is now more important to them since before COVID-19.

But while much has been written about

the fashion industry’s impact on climate change, less well known and well covered is the industry’s heavy footprint on biodiversity. Broadly defined as the variety of all life forms on earth, biodiversity matters. We rely on it for food and energy, and we depend on its irreplaceable role in sustaining air quality, providing fresh water and soil, and regulating climate. And yet biodiversity is declining at a faster rate than ever before in human history. One million species, between 12 percent and 20 percent of estimated total species, marine and terrestrial alike, are under threat of extinction.

The apparel industry is a significant contributor to biodiversity loss. Apparel supply chains are directly linked to soil degradation, conversion of natural ecosystems and waterway pollution.

This article examines the apparel industry’s largest contributors to biodiversity loss, how companies can strategically mitigate that loss, and what brands can do to boldly lead the industry’s biodiversity efforts.

Apparel’s contribution to biodiversity loss

For several years now, apparel companies have been active in the fight against climate change, launching myriad initiatives to become carbon neutral. Biodiversity is a distinct but related issue. Biodiversity loss and climate change are interdependent and mutually reinforcing—one accelerates the other, and vice versa. For example, protecting forests could help reduce greenhouse-gas emissions. In turn, the rise of global temperatures increases the risk of species extinction.

Because biodiversity is such a complex and multidimensional landscape, and ecosystem degradation is so wide ranging—affecting oceans, freshwater, soil and forests—multiple metrics and indicators are needed to measure impact and progress. Setting targets and accountability for such a complex range is much more challenging than managing for the single metric of greenhouse emissions.

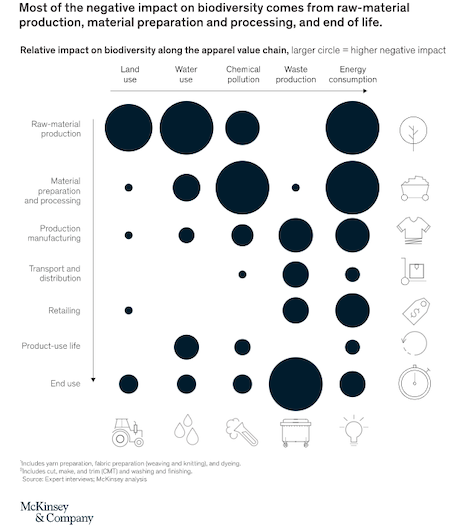

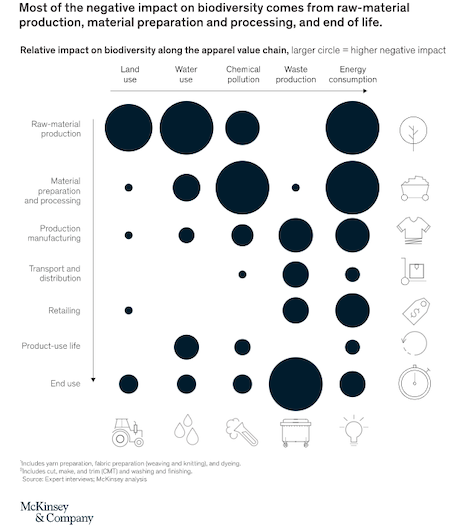

Through our analysis of quantitative impact indicators as well as industry-expert interviews, we have developed a good understanding of how each part of the apparel value chain affects biodiversity. Most of the negative impact comes from three stages in the

value chain: raw-material production, material preparation and processing, and end of life (Exhibit 1).

Most of the negative impact on biodiversity comes from raw-material production, material preparation and processing, and end of life. Source: McKinsey & Co.

Most of the negative impact on biodiversity comes from raw-material production, material preparation and processing, and end of life. Source: McKinsey & Co.

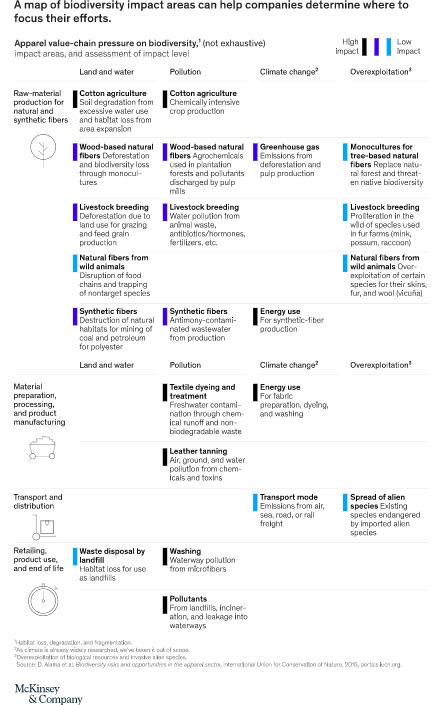

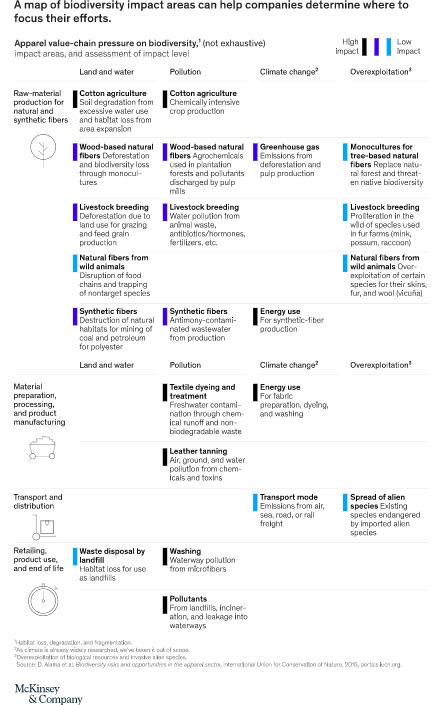

We also have developed a map of biodiversity impact areas to help companies determine where to focus their efforts (Exhibit 2).

A map of biodiversity impact areas can help companies determine where to focus their efforts. Source: McKinsey & Co.

A map of biodiversity impact areas can help companies determine where to focus their efforts. Source: McKinsey & Co.

Based on our analysis, we have identified the apparel sector’s five largest contributors to biodiversity loss. They are presented according to the fashion value chain, not by magnitude of impact:

Cotton agriculture. Cotton is the most used nonsynthetic fiber in the world. Farming it is especially insecticide and pesticide intensive: although cotton grows on only 2.4 percent of global cropland, it accounts for 22.5 percent of the world’s insecticide use—more than any other single crop—and 10 percent of all pesticide use. Cotton is also a water-intensive crop; some estimates suggest that 713 gallons (2,700 liters) of water are needed to produce one T-shirt.

Wood-based natural fibers/man-made cellulose fibers (MMCFs). MMCFs are created from cellulose, mainly derived from wood. According to estimates, more than 150 million trees are logged annually for MMCFs. While the majority of MMCFs come from tree plantations that are certified and sustainable, up to 30 percent of MMCFs may come from endangered and primary forests. Furthermore, water and soil pollution from chemicals used in plantation forests and during pulp processing drive habitat loss and endanger species, unless the process is 100 percent closed loop.

Textile dyeing and treatment. Approximately 25 percent of industrial water pollution comes from textile dyeing and treatment. These processes overexploit freshwater resources and contaminate waterways through chemical runoff and nonbiodegradable liquid waste. Of the 1,900 chemicals used in clothing production, the European Union classifies 165 as hazardous to the health or the environment.

Microplastics. An average of 700,000 fibers is released in a standard laundry load, and a half-million tons of microfibers (which are a type of microplastic) end up in oceans every year. An estimated 35 percent of primary microplastics in the world’s oceans originate from the washing of synthetic textiles. Toxic chemicals in synthetic microfibers poison marine wildlife.

Waste. Only 12 percent of textile waste is downcycled (broken down into its component materials), and less than one percent is closed loop recycled. Nearly three-fourths—73 percent—of textile waste is incinerated or ends up in landfills, which release pollutants into their surroundings and contribute to habitat loss. Anywhere from 30 to 300 species per hectare may be lost during the development of just one landfill site.

Apparel supply chains are directly linked to soil degradation, conversion of natural ecosystems, and waterway pollution.

These are sobering statistics. For the apparel sector to slow broader global biodiversity loss, a radical shift from business as usual will be necessary.

Four intervention areas to focus on

The good news is that

apparel companies have started to pay attention to this issue—and have the power to truly move the needle. While apparel companies can take numerous potential actions that could be relevant and synergistic, each action will come with trade-offs. Based on our analysis, apparel companies would do well to prioritize the following high-impact strategic interventions:

- Scale up innovative materials and processes

There is no perfect material. As discussed, each of the most commonly used materials in the apparel industry—cotton, MMCFs and synthetics—has a negative impact on biodiversity. But each of these can be made more sustainable. Furthermore, better alternatives do exist and could dramatically improve with more investment and innovation.

Improve the sustainability of cotton, MMCFs, and synthetics

The agricultural techniques used to produce raw materials have a significant effect on biodiversity.

Multiple technologies that are already available today—precision agriculture, integrated pest management (IPM), and micro-irrigation—reduce water and chemical intensity to a certain extent. A broader shift that includes organic and even regenerative agriculture has the potential to go further. But as we mentioned earlier, there are trade-offs.

Organic cultivation restricts the use of fertilizers and crop-protection chemistries. It’s also, depending on the location, been shown to use up to 90 percent less blue water (the rainfall that enters bodies of water, the main source of water used for irrigation purposes). Regenerative techniques—both organic and nonorganic—have shown the potential to restore soil micronutrients over time.

Organic-cotton production is unlikely to be realizable at scale and achieve the efficiency of conventional systems. Currently, its market share is just one percent of the total cotton market. It typically yields 15 to 25 percent lower harvests and has more volatility during the production cycle. What is more, converting agriculture production systems to organic is challenging, especially for small-scale farms, as the conversion process can take up to three years.

To find a scalable solution, the apparel industry needs to consider how to optimize global cotton production’s environmental footprint. That will require supporting multiple production systems that balance efficiency, environmental stewardship, and farmer needs, which together must also meet the demands of the end customers.

As for MMCFs, many brands are already sourcing them from plantations certified by the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) and Program for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC). And as for synthetics, some brands are reducing their use of fossil-fuel-based synthetics in favor of sustainably sourced natural fibers, recycled PET, or biobased synthetics. These alternatives do, however, have limitations. For one, biobased synthetics break down into acid in water, contributing to ocean acidification. Recycled fibers are technically complex to produce. And because MMCFs and synthetics are by-products of other industries (such as the paper and pulp industry or the oil industry), apparel companies have less influence over how these materials are produced.

Invest in textile innovation

R&D into material innovation has yielded numerous lower-impact alternatives to conventional fibers. Lyocell, a cellulose fiber made from gum trees, and Spinnova, made from wood pulp and agricultural waste, leverage closed-loop or zero-percent-chemical approaches. Biodegradable polyesters and biopolyesters are made from nonsynthetic natural materials like starch or cellulose. Recycled fibers not only repurpose waste but also have a lower biodiversity footprint than virgin fibers.

Scaling up the commercial availability of these innovative fibers will require investment. Economies of scale should help reduce price points, but these newer materials are likely to remain expensive, used only by sustainability-minded designers. As for recycled fibers, scaling will depend on whether they can be made more robust and less prone to shedding so that they don’t contribute to microplastic pollution, and on whether recycling blend textiles becomes viable.

In the absence of effective regulation, waterway pollution from textile dyeing and processing requires a tougher stance from apparel brands.

- Take an aggressive stance against waterway pollution

In the absence of effective regulation, waterway pollution from textile dyeing and processing requires a tougher stance from apparel brands.

Because many suppliers in developing countries lack the resources and knowledge to monitor and track the chemicals they use, brands need to step up and engage with suppliers through education, targeted investment, and stricter accountability to establish basic certification standards at scale. At the very minimum, suppliers should comply with Zero Discharge of Hazardous Chemicals, Manufacturing Restricted Substances List (ZDHC MRSL), and Wastewater Guidelines, which regulate the use of hazardous chemicals and wastewater discharge.

Once standards are in place, brands and suppliers can pursue more high-tech options to reduce nonbiodegradable waste. These include moving from wet processing to waterless dyeing, which uses supercritical carbon dioxide, or to digital printing, which reduces water and chemical dependency. For example, Netherlands-based DyeCoo’s waterless dyeing technology saves 32 million liters of water and 160 tons of processing chemicals a year.17 Advanced wastewater-treatment technologies, such as purifying water through reverse osmosis, are also highly effective, with a recovery rate around 90 percent and the ability to reuse treated wastewater in a closed-loop system.18 In addition, apparel companies can switch to “greener” chemicals (such as plant-based instead of mineral-oil-based lubricants) or natural dyes, which generate less effluent.

Most of these technologies are well established. The key hurdle is higher cost. For example, DyeCoo’s waterless dyeing machine runs from $2.5 million to $4 million. Apparel brands need to consider how to work with suppliers and potentially local governments to finance long-term investments in cleaner technologies.

- Lead the way in education and empowering consumers

Brands can help further educate consumers about what they can do to minimize the impact of their actions on biodiversity loss. Simple behavioral adjustments and consumption choices can have substantive results. For example, just doing laundry differently—specifically, in the following three ways—can make a big impact.

- Washing in cold water. Laundering synthetic garments releases microplastics into the water system; the more water used, the more friction happens between clothes and the more microplastics are shed. Changing washing-machine settings from delicate to cold express cycles can reduce microfiber shedding by 57 percent.

- Filtering microfibers. Consumers can retrofit microfiber filters into their washing machines to prevent microfibers from entering waterways. An even lower-cost solution is to use fiber-collection bags, which are essentially specialized laundry bags that can catch 90 to 99 percent of microfibers before they enter water systems.

- Using water-efficient washing machines.Consumers can also pay attention to water efficiency when purchasing a washing machine. On the commercial side, waterless—and nearly waterless—washing machines can save up to 80 percent of water used by traditional machines, plus they limit microplastics shedding.

Another way consumers can have a disproportionately positive impact on biodiversity is to get more use out of clothes they already own. Using a piece of clothing nine months longer can reduce its associated CO

2 emissions by 27 percent, its water use by 33 percent, and its waste by 22 percent.

In addition, consumers can reduce waste through garment repair, recycling, and resale. Prominent campaigns by retailers such as H&M, which accepts any brand’s clothing for recycling, are gaining traction. Brands have extraordinary influence to market such initiatives, ensure they have consumer appeal, and shift consumer mindsets and behaviors.

Besides helping drive consumer awareness, brands can incentivize behavioral change—for example, by offering small vouchers in exchange for used clothing. The industry can further push by providing viable business models for repair and reuse like Patagonia did in 2019, when its Worn Wear Program repaired more than 40,000 pieces of clothing.

- Relentlessly pursue zero waste

One of the most powerful changes the apparel sector can make in the interest of biodiversity is to simply stop making too many clothes. Average overproduction is estimated around 20 percent. Manufacturers recycle roughly 75 percent of preconsumer textile waste. But the remaining 25 percent primarily ends up in landfills or is incinerated—without ever having been worn, though some of it may be donated.

Demonstrate bold leadership

The general steps that apparel companies can take to help

transform sustainability in the industry are well known. But if the industry is to make measurable, significant progress on biodiversity specifically, companies must demonstrate leadership in the following ways:

- Manage for biodiversity like you manage value creation. Factor biodiversity impact into financial reporting—for example, through impact-weighted accounts or environmental profit-and-loss approaches—and manage it like financial performance. Commit to forthcoming biodiversity science-based targets to further channel internal sustainability-related investments.

- Shift the paradigm on supplier engagement. Upstream biodiversity interventions are complex and can often have associated costs. Collaborate with other brands to define joint standards for suppliers. The suppliers will benefit from less operational complexity and economies of scale, while brands can push for more stringent specifications rather than dilute them to the lowest common denominator.

- Invest in the broader ecosystem to accelerate and scale innovation.Team up with other apparel companies to invest in scaling and industrializing emerging, low-impact technologies and substitutes for nonsynthetic fibers. With a multitude of viable options on the market, the priority should be on focusing investments to establish new dominant materials and processes.

- Push for change in adjacent, relevant industries.The apparel sector is closely intertwined with the agricultural, livestock, and chemical industries; all face similar challenges in addressing their biodiversity footprints. Pushing for closer cross-industry collaboration through working groups and roundtables will be mutually beneficial to all participants.

- Engage with policy makers and welcome regulations.Be proactive in engaging on meaningful biodiversity regulation. Existing regulations such as the EU Single-Use Plastics Directive or Extended Producer Responsibility schemes (for product disposal/recycling) have helped make sustainability a shared responsibility.

WE EXPECT BIODIVERSITY to become

an even greater concern for consumers and investors in the coming years. COVID-19, instead of slowing the trend, has accelerated it—perhaps because people now understand more deeply that human and animal ecosystems are interdependent. It is time for the apparel industry, which to date has contributed heavily to biodiversity loss, to now make bold moves in the opposite direction.

Anna Granskog is a partner in McKinsey’s Helsinki office; Franck Laizet is a senior partner in the Paris office; Miriam Lobis is a partner in the Berlin office; and Corinne Sawers is an associate partner in the London office. The authors wish to thank Katharina Buhtz for her contributions to this article. Published with permission from McKinsey & Co.

Tracing the source of organic cotton to the farm and through its journey across the supply chain will enhance Kering's sustainability credentials with end-consumers. Image credit: Kering

Tracing the source of organic cotton to the farm and through its journey across the supply chain will enhance Kering's sustainability credentials with end-consumers. Image credit: Kering

Most of the negative impact on biodiversity comes from raw-material production, material preparation and processing, and end of life. Source: McKinsey & Co.

Most of the negative impact on biodiversity comes from raw-material production, material preparation and processing, and end of life. Source: McKinsey & Co. A map of biodiversity impact areas can help companies determine where to focus their efforts. Source: McKinsey & Co.

A map of biodiversity impact areas can help companies determine where to focus their efforts. Source: McKinsey & Co.