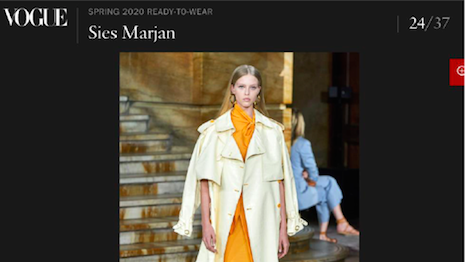

The models suing Vogue and Moda Operandi allege that their images were used to promote sales of expensive, designer wares online, all without their consent and without paying them license fees. Image credit: Vogue

The models suing Vogue and Moda Operandi allege that their images were used to promote sales of expensive, designer wares online, all without their consent and without paying them license fees. Image credit: Vogue

It is a truism that business is constantly evolving. A corollary thereof is that as the business evolves, its legal concerns evolve with it. What once sufficed to insulate a company from legal problems may now steer it into serious trouble.

A long-established fashion magazine and a successful online fashion Web site may soon learn this lesson the hard way.

A recent lawsuit, entitled Champion v. Moda Operandi Inc., Advance Publications and Advance Magazines, and filed in federal court in Manhattan, involves 38 fashion “supermodels,” bringing claims against online designer outlet Modus Operandi and its marketing partner, Vogue, which is owned by Advance's Condé Nast.

The models allege that their images were used to promote sales of expensive, designer wares online, all without their consent and without paying them license fees. This, they assert, violates their rights under federal and state law.

This new case highlights, as a company’s business changes the importance of re-evaluating its legal strategies.

Fashion images can implicate different intellectual property rights, which may be owned by different entities, requiring licenses from – and often license fee payments to – more than one party. Counsel for businesses that use such images are well advised to consider all possible rights that may be implicated.

Moda Operandi’s online business and partnership with Vogue

A former Vogue editor, Lauren Santo Domingo, in 2010 founded Moda Operandi, or Moda. The company operates online, offering high fashion designer items that are viewed on the runway.

Moda enables consumers to shop from online trunk shows, whereby pieces from a fashion designer’s runway show can be pre-ordered, even before the items hit retail stores.

While retailers generally order and offer only selected pieces from a runway show for their stores, Moda offers its customers items from the entire show.

The platform, which serves a global audience in more than 125 countries, has been wildly successful, with Moda having 400-plus employees and a raised capital investment of about $435 million.

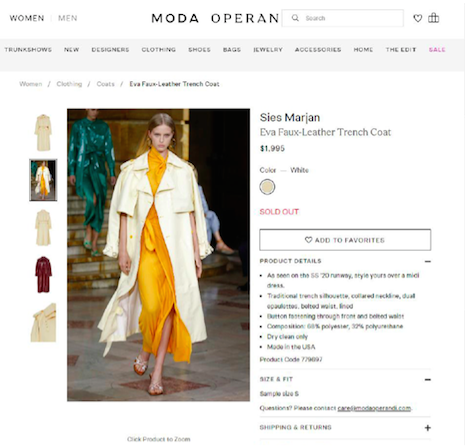

A typical Moda Webpage features a photo of a model wearing the offered item, along with information about the item, and how to order it.

Model Abby Champion shown on Moda Operandi Web site. Image credit: Moda Operandi

Model Abby Champion shown on Moda Operandi Web site. Image credit: Moda Operandi

Vogue, of course, is the world-famous fashion magazine that also operates online at vogue.com.

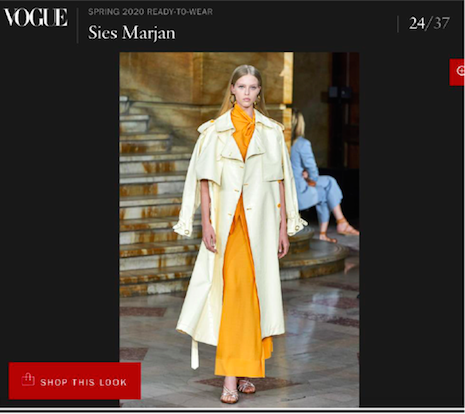

Vogue entered into some kind of partnership with Moda. For selected items shown on the Vogue Web site, the site includes a SHOP THIS LOOK button that allows the user to purchase the shown item through Moda.

Model Abby Champion shown on Vogue Web site. Image credit: Vogue

Model Abby Champion shown on Vogue Web site. Image credit: Vogue

The plaintiff models

Each of the 38 plaintiff models is represented by counsel for Next Management, a New York modeling agency. Although they hail from around the world – from China to Brazil to North America – all of their careers are said to be “centered” in New York.

Each model claims she is “well known in and to (at least) the modeling industry, and her image, identity and persona identity have been exposed and are known to the general public.”

The models appeared at various times on runways around the world, modeling fashion creations. Their images were taken both in video and still photography.

The heart of their complaint is that these images were used by Moda and Vogue to promote these items, which could be ordered from the sites. All of this was done without a license from the models, nor paying them any license fees.

Right of publicity

The models’ primary claim is for violation of what is known as the “right of publicity.”

This right was first recognized in the United States by the Georgia Supreme Court in 1905, in a case involving an individual whose picture was used in a promotion for life insurance. The right is one of state law, and can vary from state to state.

While most states recognize the right as a matter of common law – meaning judge-made law – New York’s highest court refused to do so. The New York legislature then passed a law recognizing the right, although somewhat more limited than other states.

The right of publicity is the right of an individual to control the commercial use of his or her identity, such as name, image, likeness or other identifiers.

While not limited to celebrities or other famous people, the right can be extremely valuable in those cases. Shaquille O’Neal reportedly gained more than $1 billion through licensing of his name and likeness.

The New York statute provides that “[a]ny person whose name, portrait, picture or voice is used within this state for advertising purposes or for the purposes of trade without the written consent first obtained” can sue for both an injunction and damages, including punitive damages.

The right of publicity does not include all use of another’s photograph. It is limited to commercial exploitation, i.e., in advertising and product promotion. Use of images for news reporting or commentary is not included.

Thus, for example, a traditional fashion magazine article covering the latest fashion offerings and models modeling the fashion items would not violate the right of publicity. But, most significantly, use of the same image by a designer to promote his or her goods would be.

In the United States, as noted, the right of publicity is one of state law, and the right can vary somewhat from state to state.

On the international front, some countries recognize the right, others do not and, again, there can be significant variation.

So whose law controls in this lawsuit?

In 1985, New York’s highest court ruled that because the right of publicity is a personal property right, the choice of law is governed by the residence of the person claiming her rights were violated.

Thus if a California resident claims that her rights were violated by a New York Web site, California law governs that claim. The same is the case if the individual is a resident of a foreign country.

The plaintiffs in the Champion case seem to have overlooked this point.

Although they claim residence in numerous states and countries, all of their claims are asserted under New York law.

For example, one model alleges she is a resident of the United Kingdom. Since that country does not recognize a right of publicity, she may have no claim at all.

Courts can and do award compensatory damages for violation of this right. Often, courts will look to the value of the person’s identity to fix the damages.

If the person has licensed his or her identity before, that can serve as a benchmark for a damages award. This means that highly paid celebrities may be entitled to greater damages, as their identities command greater licensing fees.

The law in New York and many other states allows for punitive damages as well.

One of the factors that often leads to punitive damages is continued use of the person’s image or name even after being put on notice of the violation.

The models in the Champion case make such an allegation. They claim that Moda and Vogue ignored their counsel’s protest letters, continued to display the images, and even added new ones to their Web sites.

If the facts are as alleged, Moda and Vogue face significant damages, since these are highly paid models, and the companies appeared to have completely disregarded the models’ – and their lawyers’ – complaint letters.

False endorsement

The models also allege a false endorsement claim under federal law, specifically the Trademark Act.

Despite its name, the Trademark Act bars and creates liability for other forms of confusing or deceptive activities, such as false advertising.

One of the things that federal law bars is advertising or promotion that falsely implies that a person sponsors or endorses a product, so-called false endorsement claims.

Although often asserted together with right of publicity claims – mainly as a way to get the case into federal court, since this is a federal claim – the focus of this legal theory is different.

As in all trademark and false advertising claims, the main concern is confusion and deception of consumers.

Use of someone’s name or likeness that falsely implies that he or she endorses the product violates the Trademark Act.

The models will likely have a harder time proving this claim.

To prevail, they will have to show that the public, when seeing their images on a runway modeling a fashion item, believes that they are endorsing the product. This is not the typical thought process of consumers – the models will likely have to employ a survey to prove their case.

If they can, the Trademark Act provides not only for damages, but an award of the infringing party’s profits from the infringement. In some cases, where the item has been very profitable, this can lead to very large awards.

Copyright is a distinct right generally owned by different persons

Copyright is another right, but is distinct in several important ways from the right of publicity and false endorsement.

Copyright protects artistic creativity. Photography and videography are included. The copyright would be owned by the photographer, or, if acting as an employee, his or her employer.

This means that the same image of a model modeling an item on a runway implicates distinct rights owned by different people. It appears that this is where Moda and Vogue faltered.

One of their employees may well have taken the photos and videos, in which case they would own the copyright. Or, a freelance photographer may have taken them, and then sold or licensed them to the Web sites.

Either way, the sites would be covered in terms of copyright. But, that would not cover the right of publicity, which is owned by the model, not the photographer. That Vogue or Moda had rights in the photographs or videos would not provide a pass to violating the models’ rights.

This is the reverse of the situation, commonly litigated, where a photographer takes a photo of a celebrity – at an event or restaurant – and then the celebrity obtains it and posts it to their Instagram account without a license.

Obviously, the celebrity has permission from themselves to use their own image, but that does not mean they can violate the photographer’s copyright in the image.

In the Champion case, in contrast, the models are asserting their rights in their likeness. That someone else owns a copyright in the image – and perhaps assigned or licensed it to the Web site – does not excuse violation of the models’ rights.

THE CHAMPION CASE is a good illustration of how what were in the past safe practices may now lead to legal trouble when the business model has evolved.

The traditional use of photographs in a fashion magazine such as Vogue only implicated the copyright right, not the right of publicity.

But when Vogue and its business added commercial offerings, they then implicated a new set of rights, owned by the models, not the photographers, which would require additional licenses.

Companies involved in using photographs and videos need to take care that they have secured all applicable rights from all persons who might have an interest.

Milton Springut is a partner at Springut Law PC

Milton Springut is a partner at Springut Law PC

Milton Springut is a partner at Springut Law PC, New York. Reach him at [email protected]. Mr. Springut's opinions are solely his.