By Thomas Serrano

Admit it. Luxury sure is not what it used to be. We blame the Kardashians.

How did this happen? Well, the truth is, it has been a process, and this has been going on for a long time. Let us flash back for a second to 2006 and 2007. Three major cultural moments come to mind:

1. The Devil Wears Prada, the movie based on Lauren Weisberger’s tell-all book about working at Vogue for editor in chief Anna Wintour, is released, starring Anne Hathaway, Meryl Streep and Emily Blunt.

The movie was epic, and though the ending is decidedly un-materialistic, back-to-basics and all about the return from luxury to love, the movie has since become a classic, in huge part due to the glitz and glam of all that high fashion.

2. A year later, the book, “Deluxe: How Luxury Lost its Luster,” by Dana Thomas, was released. It was a book that radically rippled through the industry.

In it, Ms. Thomas — who had at the time been the cultural and fashion writer for Newsweek in Paris for 12 years – wrote a solid social memoir of fashion, which was as entertaining as it was poignant. It was a call to arms: a declaration of the demise of true luxury.

In a nutshell, Ms. Thomas showed what was happening to the luxury industry, calling out “the shift from small family businesses of beautifully handcrafted goods to global corporations selling to the middle market.”

3. In October of that same year, 2007, television channel E! thrusts “Keeping up with the Kardashians” upon the world. Nothing is ever quite the same.

Turns out, Dana Thomas was totally right then, and she is completely right today. Her book, written a decade ago, was about how a business that once catered to the wealthy elite went mass-market.

Mind you, this was written pre-influencers, pre Facebook, pre-Instagram. It could not be more relevant today.

Masses are assets?

Although “Deluxe: How Luxury Lost its Luster” quoted Vogue’s Ms. Wintour saying such changes mean that “more people are going to get better fashion” and “the more people who can have fashion, the better,” back then, Ms. Thomas reached a more jaded conclusion.

The author wrote: “The luxury industry has changed the way people dress. It has realigned our economic class system. It has changed the way we interact with others. It has become part of our social fabric.

“To achieve this,” Ms. Thomas pointed out, “it has sacrificed its integrity, undermined its products, tarnished its history and hoodwinked its consumers. In order to make luxury ‘accessible,’ tycoons have stripped away all that has made it special.”

“Luxury has lost its luster,” indeed. We quite agree.

In fact, in recent months, both Luxury Daily and Luxury Society lamented in op-eds and reports that luxury brand advertising itself has gone “too corporate” and “too mass” in an attempt to hit ever-higher global sales goals in spite of a challenging market.

What the articles referred to was the massification of the luxury message: using sports, influencers and cars to sell watches, jewelry, spirits and fashion.

We can understand a house’s heritage in sailing, in equestrian sports, even in the occasional car race. But basketball? Scott Disick? Car-chase movies? What do any of these have to do with luxury?

This is our battle cry to change this.

We believe it is time for luxury to make a very serious statement by stepping back into that which makes luxury brands luxurious.

That is right – we want to Make Luxury Great Again.

It is not too late for luxury brands to recover their elite status, but it will not be easy.

Here are our top five tips for making luxury great again:

1. Be old

High-profile luxury brands such as Louis Vuitton, Hermès and Cartier were founded in the 18th or 19th centuries by artisans dedicated to creating beautiful, finely made wares for the royal court in France.

It is impossible to replicate legacy, origin and tradition. That, above all, is your story. Here is where we also strongly endorse manufacturing at home. Asian consumers are not the only one who care about origin. We do, too.

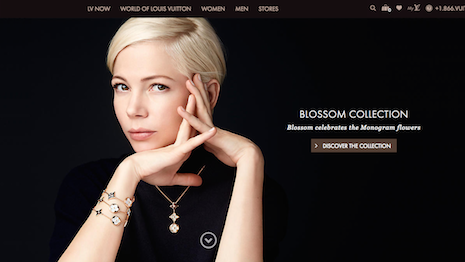

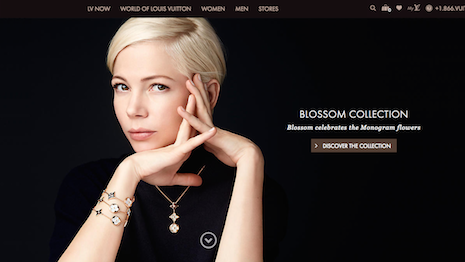

Actress Michelle Williams in the Louis Vuitton campaign for its Blossom jewelry collection. Credits: Louis Vuitton

Actress Michelle Williams in the Louis Vuitton campaign for its Blossom jewelry collection. Credits: Louis Vuitton

2. Be crafty

Traditionally, the notion of craftsmanship is associated with the luxury industry due to the image of quality and sophistication conveyed by that which is made by hand.

In recent years, though, this image has been overused and even diluted by many brands, to a point where there is now the need for a new vision of French luxury.

More luxury companies have the means to pave the way and lead by example, starting with the relocation of their production, which is a crucial step in that direction.

To compensate for the additional costs of a non-outsourced, non-industrialized labor force, luxury brands need to increase the intangible value created by the multiple facets of fabrication – linked to a territory, the people who are part of it, their culture and heritage.

3. Be elitist

When the grand maisons were founded, they catered to European aristocrats and prominent American families. As a result, luxury remained – per Ms. Thomas, “a domain of the wealthy and the famous” until “the Youthquake of the 1960s” pulled down social barriers and overthrew elitism. It would remain out of style “until a new and financially powerful demographic — the unmarried female executive — emerged in the 1980s.”

We wish to reclaim the domain of the wealthy in the world of luxury. Otherwise, read our lips: it is not luxury. How do you do this? It is simple. Pair the right messaging with high prices.

Premium is not luxury, so first and foremost, reposition your brand.

If a brand is truly luxury and wants to differentiate itself, it should target upper-class audiences across the board — those people who value the brand most and will pay a premium for it.

Cartier's new Love collection of jewelry. Credits: Cartier

Cartier's new Love collection of jewelry. Credits: Cartier

Luxury can be a tricky thing to define, and many consumers equate higher prices with more value.

Post-recession, by lowering prices, designer brands such as Michael Kors and Ralph Lauren were able to keep sales strong.

Since then, we have seen the consequences of this strategy.

For example, in 2015, shares for Michael Kors dropped more than 50 percent. Above all, brand perception was diluted – perhaps irreparably.

4. Be rare

We know this; the cult objects are the desired objects. Create the cult again. You do this by cultivating rarity – limited access, limited editions, exclusivity. This applies not only to product, but to retail, events, public relations and to social media.

Luxury brands that embraced social media are able to inform, engage, address criticism and answer questions. And they can still do so. The key is to maintain very strict voice guidelines – be authoritative, be formal, be luxury.

And here is another key: social platforms have offered luxury brands a huge opportunity to define their images and aesthetics on their own terms, and to convey their personalities via, you guessed it, influencers.

We are here to argue that luxury requires no stars. The celebrities wear and covet you, anyway. Let them be your UGC – they will.

What is our point? It is this: Hermès does not need the endorsement of a Taylor Swift. It is Hermès.

Still from Hermès' humorous video on how to tie a knot. Credits: Hermès

Still from Hermès' humorous video on how to tie a knot. Credits: Hermès

5. Be unique

Luxury is not comparative. It is time to be an individual again.

Follow your own brand, your own vision, your own path. The competition does not matter.

LUXURY: We want you back.

We believe that luxury elevates the soul. It is the stuff of dreams. It is the symbol of success.

With a solid strategy and an effort to understand and reconnect with their core audience, we know that luxury will rise again to its rightful place in all our hearts.

Thomas Serrano is president of Havas Luxe, New York. Reach him at [email protected]. Reproduced with permission from Future Luxe and adapted for style. The opinions expressed are solely the author's.

{"ct":"QjPTsIl+1dzxEw605QtZyp7jsRMn78XOco\/mJ7AvzBvFtouf15MtXj\/0dI\/nzdbgD9dVXiwTbSFYAghAUqAI4bqbjQ5MUYpxspoVwrh2FCs2ArDTV270f\/naFipzTeEbJZatDYWB5+kXwPhhYmYy4XaIunkMotmxKtDhXlOxiXi4P283pPtke6BpxvsefW73zb6nBMmfp0yapUK9gphJOn37rmh2Azov4xN8tJsoBm2ugO2GvQ7vFMn158YriQB\/5cLB3dNRpvYW1k3qqScCP2xnpjF8pH3A6Ff9QWo1+pFbQkC+kjrL3c0VCPF+xM\/oj0TctaxryFRltVHmn8f7BwODmXKNC0A3GO7oIn68nU0Kq35LSAt1y3jFCLFnqYr5e4HUMyJpHI0xXJq22m\/sriGh5TAljnV1\/aj0Kof0ZTd3ciPKmv7v8o6Sn6hwamvko\/RAOh2UxgSYIOj45qh+YiteRhMCEiwASqyoDiTZw5NYowCV04CM+fMwgy0j3odtwzIk+osPDuPNZ6inWPlzohwlAtNpJ8nCBeHu5oUyGAu75qlSHj6+j\/bWXFrNthftdEyeWye4z1eZgRuni8hHBuZM8tYVNLbTUI2xMKG+D374cbnzbH+jHtO0TpR04EKYgPVNEJ5rMKLUc9CMfAS4R+VYHw92FLp254nf7Xwj7Fa1quJG+lJ9misX3UIEE+nJ6pHXU\/Pw9EBkwX\/Xjsu5KeEdeo+wrqoSuH3ihTG6ALAwVBI+M4memIdNBZB1c0IWgBMqfVVlWOO2cU7itg6tqYOrKnEAHYICKkypp+dkQf1AMbrd5nJSLuUfDOhaF336yn5U+KLXUu9PYiazeBkyCxV6MgTFMaYuUWVs6Xw2+cQeV66QXfms8kc2ABRLuRK9y\/R+Zs3PFm2GS2xfmPeb3Oi3aRpTMndL3MoScKmRKX67I9+p73xstbsBciUb0VS5iOsp8P3617KSosh6Uxeq3\/JjSw0nokeEY7pWZyeZ8JDAXjUgQoEgiP+oh1FwdMN8DpkG7ndW8zeAb++c17q0wi13is1ENiL01wOqvoyehDpFmHvWUIW6eu7zKxLZJKfZ\/YF9T5EzyORe4KSV6cKkC5V0D\/BuMHuRaRhRCD6S8rtf8WGAJFcf+Tebgj9tgyuWJ52oMvT7fy0DRvXxT9gdU3polyfGxNlM1j7lDyFmgw4zdp3aLgn4l0pJJjMEvXT1dK8l7NRwuQjaq34ikYcRz\/wnkhxM0WlT35T8Htp\/oZR4+WVqx9jVyRXg9028HRvzvuV3H46wbcbRR0G6F0NXOvgypmwYniBZ3Hy9yzo8150kp7PM91c7peqSGXqut44SYasDxy8jYyD8Ttm++oKvwknnO+iE0Eg1lraXVl4P8jkibtZnC9FJskKtFiGt+y1Sz3ZKxhG45TIBl+VFaSYcLTKNguMiAuTMQve36Nx3iI3o1SY08WssTF6mzMv2lgUAA0FUp1MZoGCyqzZMDMcKrz4aWe76B1xNl05UdZpDfOxWo6hoOpoKsNp4BL9wkLaA2TkbvKXckzx0QitC3SZjVpfsSLcwctFTSuQODTszV6k4Wbhi7qNNGP6B3cQ7VhNyXKSm6R7OO\/wNVde6q\/JQlVCO3OizPMKCsG4oexzpwsTm+s6dHoaDu3xNGHu0eFK+b5nWiikXZrMoHJnGZRS5bHWiTiGR47HVssrgMl1QuUatNumYITBKtyoJo3qeFiW\/KNYS+0dkjpuHmkCw6ujM9pTSpkA+iNK3v72qj+9wcxxDmliVFQTI2NFqaue6bQsZdakq0V\/EYKoWuN\/OC1ij2RuQ9aPztDElKoCvXk4PYuxztr\/g113Q1u\/oIZ1buBc0rNtxyw+ar6ZPVykEV49r18+CH3i7vx1dqhD049QokBxzj+O\/TKMOeS7JTlN4xw\/SfgGYw1OMIZ0kumr9YuxKxeLXtQSFzmf93QfsK0ySLVc+gT8CVFGoREyEF2bzgJSwmwPmrE339GBjEmvDdw481NuKFHaMwGIgzmMgzrYjf\/xSfQHt+4C0Lf1WWsVlmzR0RmxVhpF3CYOiWhK+DCBCI6yGL23D8Dy9nvMn++JKU6mSEaMY7bCwII4NxfK7ZXZOm5MiQOkTc2q8rTJ+oEmIb7G1ryKlG3wf72dgp56f4SuCCXWQWpt\/6Iwr\/4rBHlQ5PHw5z0NkEWw04o08QQSPzvjsinLNILd6mMtKcztUvQRXyPoOwN\/rZT7yBXsIPg13Ro0qSTuGu42dnQIVvquppxbYz11P49clHwtV8hhaHx6DjA4MwS1uan9W+BvK\/pRh6xorlwemOAoRqGYtUnatscxNUbqDplFzMuiehyF+MUzM9sOqBsA61TG6SYqUtkvUAwh30SsNnmphJNiNzIQu4+Qr2Bq+cQa5r9ebbcXoiwvCLyutT+FfOK5YL656o8PC2c3+s\/kdcDTEeoBvp1PUM3ywNVIoRAbKSqCc9xfeTuZY5qVmfASz2aCqzSPScCcqGYq3fWZ2kyRN4yz9ZQhbtR0bGNPl56huIg1maJTNudlgqoHKyYfzITKmJm8sIHI0+fcG85VBd19zfXkMQzdSLuBoGwMd\/cNZFGy8qY\/SAO+YkdpyS3J9du4supQaFyFBfvKEYkKyJUGANCYjvEOidB6\/1ZptfkFOaWExR8hCt3bCmE8Jy7lJ1zcMZ9tqWJuCqwJalDj5sRS4SllffB6EXFSj5XY7VYzEtljmyJpDvg6v3j8Y\/qBeGApp8LKVR2sn1KWOLj8d2oTHBA1B\/hf3ci6ADfYMbeaSZWeC1ThCs6JLvRtjn7SLwkMBUFsFQTDRV\/4aHuxhWZun1hZH29GKVpiBwGTnWLFiWb7eYflEta40ehxse0uHdoIuuTcB3oB\/lxGAuN6FHLN3EDqSe989R4MPdBgA\/vNEjjAE6iDV9fskxoJ0nJR+yHrYUxO+k56JdJo0hRliXzL\/QrozuqMLV2yfKI3DediAXAhKdznR9q5Wm\/h28N\/WJ9c\/QruJgMSLfeSprshnPbTQ+96YcBYh9ft8ZkQySPWZYnTIq3XhddBugLQU9JVrS0rZpynJN1Zp6GxRGgL0JNbazoQjtafaXH4vEgdhi1EdFooimefYRIl+ji0OOjGTNJHAi+b0pBjqGN9Tuc+Z731tU5fGgHEsF1lEUOSmogcwHKwQtcNOnuKae3lw827A2RBSggSd8NxQcmU2gfE5UfB\/1UXspcdvt\/kq\/FhXeyZs+HKHQQxk\/2xlGox7RvXdY+\/CY4zu3nu4hZiHV6dN8w8W6EbE2RB6ivsOkMy1ulSOOGxd4R4SaWaD6xkYyNVjW15Ta50EFcy+RTa2ojRVAuV3uPyA4aNukZIXcfJgdB18PbsNkiZGxLJOj3kbTmKom58z2mO5VEl6MR1Etav2gQBQspYNsXYmGCPXY+6UyQEbY7odEvk8g5RSgmfTRIZkMXNu\/uQ8Wf7yO8d3+svlpE7higCTmHTDL1n4IcJz0tv4LBQ4L7EtFx1rMzykx2u3lNtKTAPKKoE7qEa8VBWBohHeGHjAJKlYYfguW7Ygy6OJOf24qQ0L2WHY5RZ06fj6ZH6Qmhp+17yn0rYImiR4SBV\/2BqbhIjGxQui4m4dFVdODMZoRP6jEC\/VmYXR34ea9zPSUJ634F8pDQMMCD+67s09YSx+snsg9cv18RJoozsSOT\/N2nDuVMEHt7b29FAJlSmipv2GWMlRkCTUk0bXU59pqNY+CdUodQWWfViG+x\/H3v5TfE6JkHQqWzq185VporiAzAR4TKQ93c71EAuT4ckLnm3IxGz94K0pC4TBf3XVYv8EOcsOxVfDBw2txevSVMghT3vBM4t9WGcppQDPzmfLbjSYUwQGOX+EXhdVQSSWY5zNeSgBjftW4OQH6iP5AgdJwU6isRgTxUq6WOMu9\/1CicoaIXwGeIk4IbG+bxu52cgVSzldHHLijtgm3\/IG43XS4Sm0gv+R8XSiZoUXHMLKB9\/YO0b9cA3ipRVtVK1wNnQ0zD\/8EmpHHRzIV1Uojl784nydYAtyMv6+Qnc5tbzp48UUn7TiwK4i5P48SJBhK+PkFQfrx31bDNU941OSeI++Tg5Xf49P5rPthA9u0bdVKMqnlSoPr6mhhtfEl+ul5o0H1MrpT2E79zN+RQMfFeXHm+gBQ\/edJ2jTKcmXI5TD0bbVFyTv2ueqf2ok\/nSnKSfEs70NfdU9ozmH02CKKQhVNn70kD4EWU\/1HG5pUN5oEpXEvN10QRWzkZYeqx2kF9ofB5SI53yOvZj+98LHO78b9EWtcChWgp\/yUAYbWhfW2mDSTnkSCxeS9trqfON42vdYil1DwM\/APJ2e1qiDOPyo4\/HVMdHozNNlpUGrljKkhhSPEE7I297o4HIORx7hWrhsF8BVZyxJbGfR47gcV7XAEUhk8Ce+GfNHyhyrqax6eQJRIt4O3+7AqF\/+h0vGE8o+1XOm4DYlURdEMFU1dBSwkx2aXcn9YtKmbJMKcvBpkfkXjtvqXcPFH4GrbJ\/1Lp4WSW8mbt4Tb3ccq8iDO1RV8FNeZ\/QGruL\/punZ2eJ\/zDe\/rXiC0FGCdKVhXey9wXoHw0WbXhX4GbMwobhvt0Ng5kcVHaYmQ\/4U7d252uiMNBitH973l+dqliWSuYzwHvpzsaKgmLJ\/qdZAsI8fA85tHnRwOT\/o\/OGAuXIy5OPyimSyyUHI01pphkyemfokF4SmYD1H9jN5xiHT\/qDd7b3T5DqcmrXatKEJ8QW5FcOlbRLrF6AJ8ItQ7tuEH6IlkvA\/KKkcueOheySzK9Rop6GJOLgEpICtPHsZsYcrlJTrCGE\/o6yQtFfb5ggVidskGHOWv5khqloiqbWDO+cPHUw5URGa3lIshst+1rn0pgBD9z1y791vl3UMHmQWmeLh3EUU8pBIp78B+lN+gLabPFDKNzmdJ5Oj9Tb5kW5ZQOp78M6Y2e0lFCT2nQWw3maDjjJh+Y9trfbx1qw2G9kdWVILFLXFJ\/5\/K9I4eGHEChIqJ6JnpTCV7EV\/uRJ2CLR\/Jy+rp\/uqARsu1Q5nSuUKz9CbdW8ajSVnmKQa78xoUHujADISmhedHGvNNqv0zz0DYLHX\/oQ3iRuwlbj1cIRCTE6Jk6IsA12504qVuDOU8k6zeED0E6nCCF7ElZyhnmTDHCwn6Qh2LxBQH5W5Qzowv+n7Si3VfjVSo0sIfe3oXsLNR4MXNQxTzwgfU4E2P32p6IIVFcPNo53ivLIi4dUZoNCy8EqctTJqeFsjQAQTgn7B5uXvnk6jUFuW21866dzXysUalP\/s4swQDam0ee2N\/n8DmkLjVFY59xBSIw6lSkNxXtZDySsEQ4saLctcHU3WnqFoeNPe0GgAN8ysyJDgu3XhvrYgvqJITKvMPkKO3aGSl1dflUJ7yHbkRKuABcbZmfEi7ckg03fKAHmoaxGemkzny90OHyORxmdd8+vzBf\/PQG9IJpNRA7Fm8pnHdSqm0p\/15WuWSeTiWPiess2xTEZXp6krYTqtrE+q\/Vih3D09HFFOZZpmZFE0X2i29LEeqxsUnA0kvBxHSwWrjCAyBWaRasXiaWTgmQNV60BGVxp\/at1P9ejXYAsh09EYh0zgcIY0k6S35zjSUB7iq4KTa\/jCbPVq63OHSr0CiiKmvrATQmhqdUsuhvKZAVmN+lPPfz5mc65RPdXZsZvgjAaGO0P38J\/9WDcAI16wyRk2a\/ds1K2wHmVEwNoGep\/9ij9V9DP\/rPLhFocD+zWYNrsnRyLcqrPxnKHD\/XQ2tyGrIPkHEgZfPeCPOZyVDf73u+mnnXn6KIAidoQtjxi5kUYyMxSWXs\/xi794\/keNNT\/U6aHySjzI5wkp7CqHi9eLNneWEhfJugE8EP0yVsJn68dOZplYkuZzCNh\/1YnSlVFDoO4nZysfgEgz\/QGrpE8QHZpE4CsK0wI\/MyNRTHGA9HyvTQ8ncvO1hUeQS7GYFi03Y\/1akymjkeLN6UNRoOMf7eXrSWePslCD0WbJmnG3YrHiuSCRTnsZKMtWDrdM8vAoISysDDKp3Lx4HKklOAuCFxWSDIBSnimTUypdxfZ4UDtELgaBUT\/\/RXBs4GWWK3g8nBqZwBVcdHsibtJOQEIZ6WK\/JVEauFHNA6Z4zVmfZxoQz2dGiKJOzeTgggUOmoQWCpJ0BeEsA8DhAgOV+eH711MnTHhLef71XYKnk7Q23Ezq8imLuGLdTj7jJO\/SklyPrKw7ESvqlSTp0oS9jRAfolOddoe+Mfh3N06HPA0WAqDuqY3NQsvyhmi+y2OdZszkrt012hwd8AlIDdTeJh07mJdOO3Sjnp39bIFUGQyUAP1UQzUy3+yrpkQUv6lxqYJOpNQLrUoZYqtR+222VXx2yd1hNAZu7ODfgwuUPQf+MwqBEUl\/uI8xCNYdEHN7XGWxpTggeOjq0NbuVyL+XGysmqK8GqG4JhyYigjRW5V0o7s\/rJ8hj5MdwHItn6ksOIv641pMj8MmnZ60ZMgSPR1xBLqTgYVgAu4ztyKrAhMVYLJ7\/\/7aSF0JEDkoY5pEQP9hHQhRv4mcN2FpY9R8sAKE10aqd2ftDlcoK7IFPz9zqQ26WGEBVHceQLMUOn1MPuI4rT4IXpouBw3LknflCHkZVd8ztYoKuDNk1qhim8iIZztPxrBVYeMT8rRoLLL7UWbpWiqFJ\/iWGrwB8foKZrD6\/XtPbuvAGBbk2KLzXyPaokt+17FbSLL4NTT2Jf3dGYlyhRNIyMwU6bQoUcv0TMzudq323oAPKKtJm3zkCm1u+KHHD\/K0Jwe4HPbFrWJO6tGtGBBjAdHzqHTqaE7W8az04XtW07x42TByYJMFZpehoMr\/sVcImn5eghzuf3zja70MzXEJr0i\/kTv5iMlSQ8ymtP6ad31W\/Jijpdp0qmHKL049aMNAyf9W39uE47bk1IloV72iE6KtwXeDTdh8MKAvO7GuetOW\/Xtg7b5ixV626XUVwXBbmiYsHccfavZQp1JXqqZhBZIXoASY5dDzJOEoLyVllDaiq\/R5Mo+0y409i1vUKRi94WRfMPTtn\/Fp3z5MvOKqL2a4DQCUttxf0bIN4qH+W0lQuijsGM2mVX89NzpeIdYeWO7IN7O2IsO5DLc5RAqyX57hzjsso6Ae55m79YG79OpiJ3O9Aa+PTsI\/Qcgr1ls3VZ30B7Uwlk4Luq4FD0DjyAc4KGfM4lhQBZL3fXTulanRi80tvBP\/xMHwrG8ghmWfqv1Jhbow33hiE8bwKX2+mH4+mppaxRGKDA8IfoFoXfXA3rN17W4EkcMpKfBnNzfplnArtS1eUYpcD7Eb0su0ZzT5j6zHruiKmNPATcnIizpqdTLug+pK6M1uEjB2oLITEJnBUJhljAjuPIfLqw4w8VUAnHER4vwchbTJYK4wVHpaeI9sVTkep6\/yBWpkeLV61fD7W\/+aTM4oHnEOoZ2pRg6xiOP3yAuty8T2A+0mY8Sqlwh6a+YFdbUrO7sgw\/UBwGk34GZOI3OMgtbR2UNbzE\/2nL50nQCCVCQQfu1xRgtHQLVvWnVM\/Q6KR2t1sahK6NW0S4+ZuId7G9zBkk07Q4oJ80nJKOfeFddCqqAjOUIuptVyDcNg0jLiM9aMjFqS2yxi+1fvwemfzqhC0gzmjc7u7q\/TMlEjVluDZ5MsVqE6jC2yzJwj2IdZahangghfQ9oBRKMgIbu8LFCDvwv0ReG8fCInCYrX0evhQMDhc58tBWDx9Iwic5zsPBkcyXJ+7j7S\/\/xikYU3UGt+CwJo0M7n8lR0q1+UCK6kvjL0iSgGPSbPOiedBbOIDNPXaitNRb7F0XznM4cb\/BAQ53zKskIjzbGPPwj5QYO+bVj4d1hNeX46oFScVa+EgL06CY+anEeLOn0F2D2lWCNF6jCUtk85LFM\/Qrt244U2CkDztGQxhBMVAyWCSQ\/kvg66bJI7VZ4ZbHRERSYNsBkasFrit8QSpslNnoUf5KTZJ\/Ujjh8AukYcWA53J4jIfuERbColysztFEABCeeKbYK7p3yatOgVYrci5C2bOX+CMFSG7Wj2n9lRXrGxlught0BsBzCi2kWnedZnZP07YF+xM8oUwp77xQlkrVAlb\/Br5eqfVYXHczHbakAVVHmFrl5ccP+Vd857tjBfGvM8ksKvK+JkosaZiRyEaWdzM7nkZ83fpuvBiG6sCtWHIdAxT6rSBfl\/0BnBejAA3Z2q7K5aiHk8iScRUomYLOcj7mAw\/K00K8xmO7oOJ+d8GoibvMRfcBB96os5Ei3zain\/GMw6u\/kVMdfc+dJN4VUtjbmeETE2NlSUb76xuocWljEZIdGaVBQjpu8Shml+hpBWBbGvd6\/qT684X6U+HjjoTWnBAreC6AuLCA7ySNk9OI2PVVI0XeXbUimtzfm0S9utJVxjACEOGQRVbHTDY2PoSmzEXFZLns62D0S33pUOg0exG5lKJtXcU8tNFbvCwR+2zaNVytoXveBHCfvIIjTCZSXJ1DMkQaqQ13ebh\/WthCS8FXN2OTy5Gzj0EIgwx3GydOU3gye3szcugYpB4Kfnx0AkHQbAhyr8xV3UBBzE\/+LGrapUMH0pzwU4K8QIbBCV5ooLpBct0d71UYwBGc8sG70\/gsnpiKUo4WSSDzCP1rULf1v1Okiys1IGQf9F6Uzv\/0IHqW3o2lE2GwEp0gLE0DALxYYQdtsxgJ7wHEuam6JxvfUG0dRbe3fXGT+Z1XdzhuTEqIHk9SEkh7UfFnLCf5\/MfgV1gN4cnQpxv2YyD\/Y\/mG5QkupenoMLqhVMHIyCMy\/T\/YcS2eYzy4Z7Eism13ajr7M9ts9xHuqZIb0CTLkeeOyEQYQ\/b+rEeBH3gB\/2OXuxg0u4HlEPynOalmZfr5cnlVeoQh\/S0\/Ay6S5U\/KXFZHn+mcK3izciYxWkEHO2+IKVwNeVPHXHjclFNyUpH5p9JD7kASX19jAJzUJrmSZGT2XrTn\/bhkeV1IgkoVHGfwzjMMD4g6Fi2Erg51cn4KgbJhRhK1tdFaQvwhYBTmgOAq+SQyAsVv3\/Ef3ffBNmU8FG2WU+pItJ9Ze9bb3gUW3j3nuRxky\/4A6hMecwNR9GsAamNf8EdYhejitWENqB4P7HOxgduL2GZyNhWcRmLAGEb6E5IClSd4ALzE+hU9AJIXJJ+7otjPg+Db2dZg5M\/TeGtJ6DCVj7CDRDtV0zEHet+6vTcTPi176yawc4XgdbGdW9LVA6vz1ZiWhYVnjVTSzj370O4mvJyBGCXR0YvXu8ZsM14D5YJIq4mE9vYvJ\/IRqm0XbmBDBzNqOTqVH8WiQbY2TrtvaT0HTY9aSRitcCgwo3e4I7TFhvHflYdtcDwjS1aBOgdmpE1BCoGf8yqis6VfAQqqnrkTfcc9YGvD1UTyRkhZ\/EKZDOOIRg\/5DYcHJ2WaN4i9BcE22xDM8xKvOzPFuXNmUJ\/nAPucRA92NyGthNstzZtiAR4R+atD8BvctMEDrzydz9wziQWbaXgZPPhSALQLPzgthGxy7eaAHAlcBu\/qPbMZMAIUG1k304s7RxB9OvDQx7nEB579mj2KC77b96E0YsWCD\/Jwly3s3TqSYPhIPAojVDjK4p7lAeM6lxYy+tDT1C8W1lE8noaLtBwC5P9pzDBnU+0T7u05C8pj8eI9SxUdty3KkZ3gCfMPClGqrZDQ2HitupQIrreOdNoG1dPwzmrcC0+Ox4KA6y5UJR7\/od5xMmYJG7EouWT00BHREBOSVddwkiED+g3coj1FM0L9y0lDiwtGUupMarGE3ZdcCr8E6vxuu69kIrBJtuesFKeFvovIJbacQBSxDynqMfinzFqARKteCjhowp3bXmRV3ocG+OpSHlI+MvPlsbxHuA+M\/wA\/ef+uokqA3b4lT8eXYiG\/\/sA+gdBqq9+P+gh+LbFHdNNcu3QsYmIleDPcO8RhVX6Y7K+6FuiNNs9WrLCOyIEep18PYMXqAJMMUAYh2Rdu5+17p9WUkCX\/drL0TSkDGMGusl3WmpYjnQ5kcDxKqHOEXs8eYDfyikHrnF7dZ8nV0qGYxSSMFpJaS5NIRfCXHnBR5Kj+t7XuiWNaeIEiqVcom60oezUejut1HSp2cQBUR++pW5bhKKbcSDJ+CiPPakDKVM3zJPcDnAKtXKcxs2iKMMUQYwLrYJw71Xv9uNaciCmKrM\/44sMpEuQaWj7WkhJ5rm8HK4l82Z88neRqTP8vNfOo7PHNnUSXoV\/A5FCPz85ls3KEEkJk1rH5MHXAuLDbwj8daIhslYvMa63EEv3INEOxw1drHyoV8gvxNuYTOk2fjicGBnz8sxJHctEyRtnHKDhqYpbL1n8ul\/HEfbOsRVnPJ4v2JJort3LpNKygACqtkF9JDWHcpJ8PNup1knV2RwxxX3xDCu2jqlQ0jlb1CjxRskhIRi8jokjABuxglftcd+I7\/zV5zVswExVDK0SYbeWwQ67bVEBWD\/0IvDvAS6ojo5upGstVNGQ3YdlC317YpJsYvIPKi+r3YvuC8xiE99TiN10Rd\/Boieugwhr\/WOrYfEGek3P8XBXHLoYZ9MWvT+jP6SNImOZW2LENTBuSfF5pxeNQSgWcCetLcayLlB6XoezWLTvOzG5x0A5N0yUQ2adzMRicO2Tpv2vHLtP8pZVIRUAhydEEO0ZxOYQEY\/YKO8j5ipU1r56peXu8+yB1MViJ2Jb92VsEiISU3S++k2fCkBEcdbONC0N0IvnEQEYsR18OOyYNz9bcHG0qtxmGqFtneyLLjQ5fwAwjDkkDZDJpCiVYkOZQMOLyQQO08O42g26bk\/YbceDDKmmJ0y2RwnxqaAEqPHz6dOS762f8D7n7sWvmX8KicJ7SEGwjjkM0hsnKnHLVjVzvsZitGvklTMMIK5Vu+X8UmRzer0i0YUmVtwn3IMD1AkpLFGcynZt7QwMH5ePFfIoV6TpUCiT25vEehk90cnqmSSx+W37H1BneoWjtIjlAl4wQ3JB+VJbUsZ1apAiTk5SgpKSPiY5FI1fyJAhx\/Re+5zHVCHsb1C4tqYQp5hLwH3FZO3LPzgd03XiF3AwMlgQOfbYGUcTdMfPOgoKhbRsIow6qAx11k1xF4dnOP5YmHe1TD0tYY3iU73Kof2hO3FccCkZybgnSX46gTTIMXtXC3dHtA8J\/yVYC3HPRH1E64d8nMr+0jUfhgrgbcrc0F2jqEmeDEi0MTdeB+0Re3J3e\/bu+mCx7z2fsgoN8WQ95sRkY469dvRHPojnlfMxV\/d+zd56TspJvkE6BlQi8uqQxWy7S3ZiPQrYaa6cO6pVa5tbxyKFD2\/dYacpz+qeYDumb7vxgaRMvu7X\/sNteQ8m\/Wj+yDKVRv5SkgXGuBTPZxyP8iJczmOCcamtK67imZA4E46SVrbjyBWMTU4jtamE2aN2dfbHVNtXxU\/dqss05Pd7VhUZaJTFE9HJHTh2ayUh6FqqMK\/JTIKjtCqO9lkygIO0S6W1da\/py40Rqi2vz177evlETAwnTWdmxH3gm8X1FqN6HIn0OwVLN18g5bYbrRDpLVcT08N+LgnW2gShg7Oom03DZiWoVZjuSs25d9f4tIDk9hE58N2iyfJAJwTthJKdb\/ia\/zeYxV82r6G6t03aCV0Y0YSsG+oDlvGNQun1ai4sBQbBAS+FSw4O1ZDIUnLOpu16Gql7JWbht\/M\/8cci5m\/wM9k6Awi25aiyiK+HRyGQPqUMwrVHdxn9Eg4dxbk1b71xfAKXWfoWUgq0sy+AtjHU+bMpjFk7XplDew6rTefs4Bg1ZSgQFUSXUCKwYVA1AmXR1BG3VChvG5Qw7VtJWVjh8MNW+npLOEqZq+6gfxXtaKagbKict+OOb0cT9f3Phax4wGqpZYRoA83RH3fUxu\/q1zClJQiw5VwtbegX\/sz+1gqUZJv5XulNHc6aKKvnqA2KNuFp14ArXwzabZgf7MB+1x3RhyrF7Ev4u2yK0QAPFaPzoRnX\/j5DN13XVRIzcHcfjWdRefqNBNatDr9pz4cYM\/xCh9p0c5SrFs97ex1VD1mjVNHXPMVJ0gQmTAQCWVR3qsJOWkwVwP9wrHH+qx4L14hfKkpL\/qnh83hnoZrqCOjWVG9RSmWdfbjx7elK4cctyQEiqFZsZmd+t795hz3KBNNDX9QFHGnPDj7c4hOtt9OdAMr3iI8gxcZpbOUy6t++EsdP2VGiomkD0fnEroXOU0EH6Z5u5H3WduRSKyg0PceRXpIK5UbKpWqdief8rhiLCtV\/GTaIzNsXEPL\/Ffonk5GfbauqDPAOuEipfNBaWNrIMV\/MCdfie4nh27yysbALZ6R2aWrvgwm7C3wcaZOAqNJu0MUb43bjdt1DQRYA\/5Mc7i43rc7b+Sb2\/eQphT6HCzsbh3LIVnDQ19pcQALwh77de59kTJWQ\/V8hUXaZr+uVKrWjFGMBuWhR7\/kZr6WH5vHdFhtHj5lTR1KD8aXdVjlwC3lv3meyHBALbvDuW6Jni1m2TfU6OIZx45v+\/DyFmCfiPfyvbF4c2foI\/HsNhwZYtGPAiLFWC8Lppr\/3g2gJHJ3immC3hYB+KJE3q9Apb6RNIMb5pc3O8L1F0rgs8PMa6NeVn9IzGfoIK83tuipSyqBNpW1jn1VKqJcnRxc50uJo02MBefel93Pt+XXK2S2ASaTQ340jjfFe64KEAy05G3afW+VVOGiWl4XhNrO3z6bbEqW6u0AVKEN1YFbcBr49wOZImjFicZ\/z9Ufbrw7gGA+b86FoHU6E4TxZp\/bEQ0Ap3Ozj1ylqI4PymTR9hgH2hb1jDk1JP\/n06PtxnuHv4hPMu30pNRy31yRGgH3Fu27ieQi7WqE3lJy7xj8OTcoKj6z0jdVF7k\/ogidPoq1afq2\/\/qJzotacS8937lo5BAqfAklZoOTOLMnpLMiO25o+cd068pWm\/D6\/UqV9c4a5f5fZzhjqJtuR\/my1gIa9GQt9hZNeFMU6g2QqqZNqtwZ2aVxpTnxDBdCkYq2O7qkL3G6SM8LXuK0QF4nCF0mEKEqd2nuCaYMDz9Owsk+dvoYH4Ig+QfEiSuBwXteWmkHjZCxiwGyNIL8NmqtZPKdtmgYtzH7HkXskMollpHKaT5JLkke9U7ymIChFEKZn2FM7X1KyYZCr3pYCCKZBuB91XXtXZYmzIUm6P0qSHhr9nf2+s9XRbA7sNRv0XEj5Kwtd4DwqHLq+CBtxzqOThMSk0LC1OV7efJixm35\/A9\/n6q3QnJqFW\/o+uK0SyAy9G6RzwAfN134yu8\/LpQn\/d94nEPbA2CYrV7rOEFOwkZp7fMfykYrUBmtNH6bZral6MeREje+IkriagW8E63Iz6JPniNaCRhwQrtILmrAMd+f0Sre6sRYoP8mIx896ldw0IZPuHMDgk3KY5d+a\/QhVe\/62xotcg+VcmLf50e2qQZpiSqW73o8hkXPrYRdfat8IYYBu7hL2FmzoEJh7H6955gif5SsYsUAiJdaB372m3oBRQHzxRYq6EmW13SZ2DE2QgPsBB2KgKmoD4\/0zOQCQTpmFiBJXG0+1RYiQvj0yM6M3mV09qnhSWl5DxCCLVd6DgXjnAaJiZIQOBYHn8JnNMYCC431SFF6q9rWam3E9oMHzgGUTB4EaygiA3uE6UT4DDdepUAYPgbg6uo1KKxa+Kan1EPo6qpekIP0AB4NCQ\/rQvn3JAbR325zz\/yskz+W\/TgPseTUAR0KsNzRKGM7T7is8HMaCvUdCZPVN6SN5QjL0kTk9cOCmHACZ8EPzljwISlrCB\/MrLMNqX7rnsiYY0UCVhaOpBW1vRzXzNfLP2UktrRBr1mx6fcoZZfk6weC9M1J3cw=","iv":"3a2c9f0e7f796b869f26db1c37e37283","s":"e724b8575a904eb4"}

Louis Vuitton's new collection, accenting heritage Monogram canvas with colorful leather details. Credits: Louis Vuitton

Louis Vuitton's new collection, accenting heritage Monogram canvas with colorful leather details. Credits: Louis Vuitton

Actress Michelle Williams in the Louis Vuitton campaign for its Blossom jewelry collection. Credits: Louis Vuitton

Actress Michelle Williams in the Louis Vuitton campaign for its Blossom jewelry collection. Credits: Louis Vuitton Cartier's new Love collection of jewelry. Credits: Cartier

Cartier's new Love collection of jewelry. Credits: Cartier Still from Hermès' humorous video on how to tie a knot. Credits: Hermès

Still from Hermès' humorous video on how to tie a knot. Credits: Hermès