By Edward Hamilton and Chris Mellen

It is not every day that the vocabulary of a soft science such as consumer psychology overlaps so neatly and precisely with that of financial engineering.

But when it comes to placing a value on luxury goods and their producers, it is indeed all about the intangible.

Valued for money

Consider two women’s scarfs. An evaluation that focuses only on their physical attributes—both are 100 percent silk, beautiful seashells print, impeccably finished edges—does little to explain why a shopper will pay five times more for the one that says “Hermès Paris” in tiny letters in one corner.

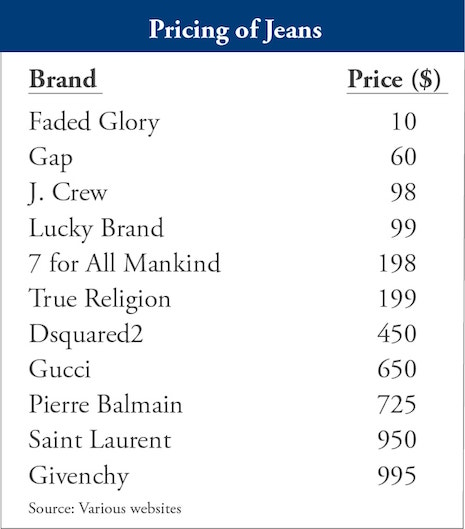

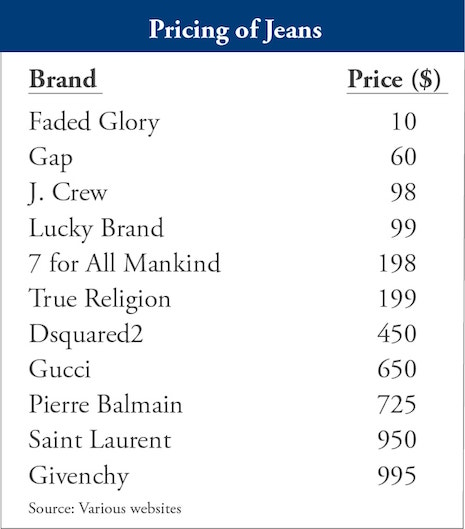

The same principle applies to casual-wear trousers made of heavy cotton—AKA “blue jeans.” In the luxury market, brand is everything.

Pricing of jeans. Source: Various Web sites

Pricing of jeans. Source: Various Web sites

That axiom also extends to valuing luxury brand companies.

Practitioners, of course, consider the intangible value of a brand when assessing virtually all businesses.

In heavily commoditized industries such as basic materials, or in high-tech, where customers are generally buying the technology and not the brand, enterprises will still attach some value to their name.

But in the high-end luxury market, where virtually all of an enterprise’s value derives from its brand or brand portfolio, the ability to accurately assess its value—to quantify and render tangible the intangible—is especially critical.

Luxury landscape

Luxury brands are characterized by providing experiential benefits such as social status and prestige as well as premium quality.

Historically, such brands were smaller, closely held, single-brand companies. Today, however, there are examples of large multinationals that control and, in many cases, cross-market, a suite of luxury brands: LVMH (Veuve Clicquot, Hennessy, Givenchy, Louis Vuitton, Hublot, Tag Heuer), Richemont (Cartier, Jaeger-LeCoultre, Panerai, IWC, Montblanc) and Kering (Gucci, Yves Saint Laurent, Bottega Veneta, Ulysse Nardin).

There are also prominent single-brand companies including Burberry, Chanel, Tiffany & Co. and Hermès.

These luxury companies uniformly realize their brand is highly valuable and fight hard to maintain their image by associating with celebrity personalities and prestigious events and locations, carefully controlling when and where their products are distributed, resisting the ever-present temptation to discount prices, and aggressively protecting their trademark and combatting counterfeiters.

The stakes are high.

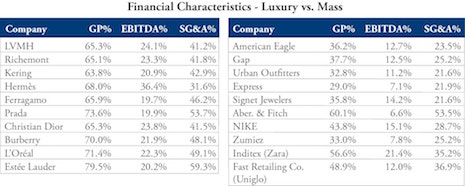

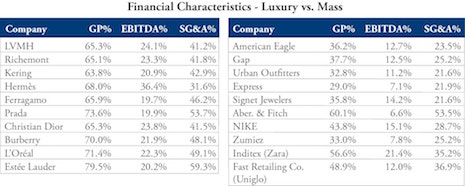

As the figure shows, luxury brands can enjoy substantial advantages over their mass-market counterparts on several important financial metrics, including gross profit and earnings, even as their SG&A (selling, general and administrative expenses) is much higher.

While the margin earned may be higher, the overall size of the market may also be smaller than mass-market brands.

Financial characteristics: Luxury versus mass

Financial characteristics: Luxury versus mass

The luxury market has benefitted immensely from growth in emerging markets.

Another tailwind for the luxury space is, paradoxically, the much-discussed trend whereby the millennial generation eschews material goods in favor of experiences and identity.

After all, the value of that $400 Hermès scarf is more wrapped up in experience and identity than in its utility as a material good.

______________

"It is not enough that a product is well-designed and crafted with the best materials and workmanship. The luxury brands [that consumers] treasure have the rare and intangible quality of truth.” – “The Emotions of Luxury,” Psychology Today, Oct. 12, 2016

______________

Why luxury brands need to be valued

There are multiple scenarios where a brand’s value needs to be calculated.

In the case of an acquisition, IFRS 3 and ASC 805 require tangible assets, identifiable intangible assets, including brands, and goodwill be recognized at fair value.

In an impairment analysis, ASC 350 and IAS 36 may also require the valuation of brands.

Brand valuation can also be important to the tax treatment of company restructurings, in litigation—for example, to calculate damages, in financing that is secured by the brand, and in insolvency/liquidation.

And, finally, knowing the value of a brand is critical when the brand owner considers a licensing arrangement or a joint venture.

ISO 10668: A roadmap for brand valuation

Though not commonly applied in a formal sense, the ISO 10668 standard provides a helpful framework for measuring brand value. It specifies three types of analysis that need to be performed before rendering an opinion on a brand’s value.

A legal analysis defines what is meant by a brand and which intangible assets are to be included in the valuation opinion.

A behavioral analysis entails understanding and forming an opinion on stakeholder behavior in each geographic, product and customer segment in which the brand operates.

Finally, a financial analysis describes the premise or basis of value for the brand and details how the characteristics of the brand dictate which of the three valuation approaches is most appropriate.

Various approaches to financial analysis

There are three broad approaches to brand valuation—the asset, market or income approach.

In current practice, the asset and market approaches are infrequently deployed.

In terms of the asset approach, the cost to develop a luxury brand may not be known and typically has little correlation to its value.

Meanwhile, because brands are rarely transacted as standalone assets, there is little direct market evidence of value.

As a forecast is available in most settings requiring valuation of a brand, an income approach is most common.

Additionally, in one variant of the income approach, the Relief from Royalty Method, some aspects of the market approach are incorporated via the use of royalty rates.

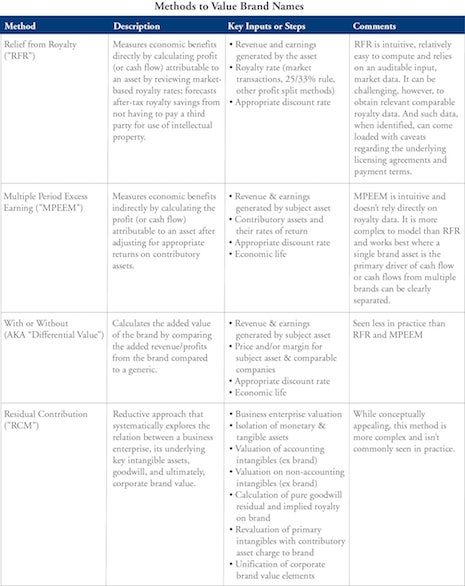

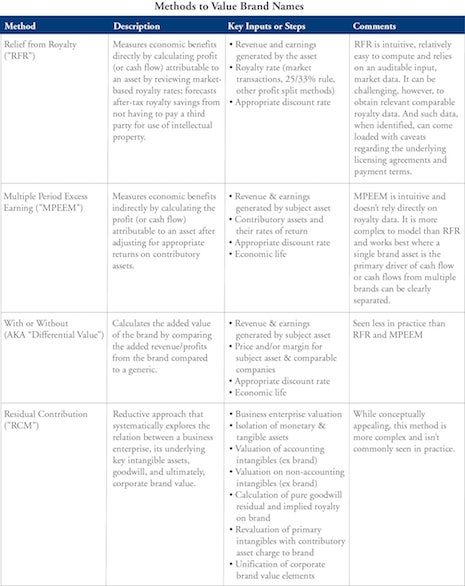

Methods to value brand names

Methods to value brand names

The table above provides a description of the four main methods to value brands, their key inputs and some comments on their respective strengths and weaknesses.

Given their importance to the business and its earnings, use of the MPEEM is quite common when valuing luxury brands.

Alternatively, the With-and-Without Method can provide a meaningful value indication as there are price and margin data for both luxury and non-luxury brands.

A key challenge if the analysis is performed from a price, rather than margin perspective, is attribution of the price differential to the brand versus actual differences in physical quality.

ACCURATELY ASSESSING the value of your brand is important in every industry, but nowhere does the brand contribute more to the value of a business than the luxury space.

Edward Hamilton

Edward Hamilton

Edward Hamilton is Yardley, PA-based senior vice president at valuation firm VRC who specializes in the valuation of businesses and assets and liabilities for financial reporting purposes. He focuses on the valuation of intellectual property/intangible assets such as trademarks, technology, software, customer relationships and IPR&D. He also values business interests for tax purposes. Reach him at [email protected].

Chris Mellen

Chris Mellen

Chris Mellen is Norwood, MA-based managing director at valuation firm VRC with 28 years of experience across a wide range of industries providing valuation services in support of tax planning and compliance, strategic planning, financing, M&A, fairness opinions, post-acquisition purchase price allocation, financial reporting, estate planning, exit planning, buy-sell agreements, marital dissolution, shareholder disputes and appraisal review. Reach him at [email protected].

{"ct":"pNtbAm9mYSFrCPNrpUE\/rUzBwquRlABim1RdF4LUx8ZJQpSut1RbvCjHr\/wnHMbNYOmlPTLS+3Q7kWDmHQLoTdlHBFafefyGNmiY5+5ftRYmTLlvOqIzlCFEK4UXbNl+7p71SEVJbzAuBTb5YhgMZt5qgwYXFUhNUeQPXQrG1tYnaKIxyeoiGSpx5moFbWVDJ6w\/4zTA7QduV5oj3vY9OqZROZUI+4csns9+P5JqS5\/HQ7dqkXGRMzmCH68IRPyE6uOgtvxxkSarB+JELGyJAcytQbfiR9BEtDvZSrNacR36+JLe1r6sm\/8fc\/NMbP\/tNCzcK3cdqupolO7vjuSamNwR3mSTb0Pft72jjr7PgSn5edwnTNbS26VFxq28qGvmypiXBtm24T+tK34JTXB6ewNB6aWroKW2au26+QLzGcFuZkbbKClzBbrccrwVIA7lVwDRn4JOU39bbRzFos1Wonur75wxg6PKqdKquD1sgYPukVJWSvpILvfnAKdV7PaD2tkILkkyRmiSM5NtLqPCfuzvtY8AZJBUQyeAtw8gQH6jztDxu5vfvhOfINHFpkOYddsCdukfwQvSd3nMBFbQJ+5\/lel\/U8NI4XIeDxcvp8Omn50iU3Z0eVInG46A5KjVcHPFpA1YUsC+37ZU1VFsK9tQ2bClFRWvuI6BkKGW1mu+5+b0VkGErC31HkeiI3eB5xUEXJh3vBWFWmkMt\/bvhOuUknuhD2gCvjarA0sIeBhg00QyBJstmJ4pO566iviw2KaHFDG0EA\/CTmOa80t9KCfHydaEH\/lGg2XNG6RQaI9lkOFLPu1Hc+G8knNEqerK\/2SZWI8N3ddBXNPmqD641TtMIOa6W6RRraXRQQMf+x6TIlgXBsYk41N\/ZJlOcc2XSEm+7jTXKgWDJT6ns9qrJKipymxv6WHVDCQTLOImJJbnNcQFJYUwnpjAe8wVbUQZw6lIMsk5NDF4sPclc6gRkquD2MuSgGviJ4hwJH8E4MoYR6dp8L97OWI\/oDTsFtT1fJmlqMqBZzjP43ZVaebkp2\/WGZgazj9DqsKDE57T6oLFAXqQQBGH4cc0kKlhoJJk3R8G9dI\/7xnvXDfgJQI4ZuSL4RMW4oZw30iVuq0aQxIaNBmc3Kk7kt\/zHZr+s9kppE2mbsiopVHurO1Fby1uAapUutHwgSm+Ljsybrw6doWwqvOry7Y\/0l9vmeP\/5Dqp7aHvILVeMzCxEoJlior8w131HHKSrWleUFiSPSSDwdzHY9KIZjPEf0seGY25LeMq8gW53ubfs\/\/Txt5Rk0nqVFseVjCQukLkagcNi2\/bzE7BuNuCk7K2gMoHxGeXywL36uq3INdB7rBpPWFxGpykPI+exarGbPLfnDDCCZ7V3KNfn\/MATnQZd\/vABrx2Izj+UUEYf7UJeiBHQc1izJ9R4nRfwjMB4MqAGzrGCHf9\/Gmh7r4kpMiQbX+MfvofSxcA2YZ9JRi1mAL\/1UWr6jdaYb2dnJk6H7Chb2VjhGa+ysvmRh2AJOThY5+Oi8BtE90HDv9CjSK6GsdV3pQMYAhsd35HCI8Y49dqgMLrVC6Hi2Nz+tv+kWOgjTI5yyTiN2giuYb8LnZp7YQTrhrk4\/GI7WVq+\/EZEa+c8s0jd68zEJpEmF9S7SLfn\/i3iXK+vCSBuQh0ZLI4tc\/0uEdywfknXTb16znMvkR1MmnTQq9aOM1NP1U75Xer66O1ELKZ9ndXlqK89s3eZSltipcdBEKlpZuMKHXWxX0cyZV02rALvmiKl16l0w+o3U73YTye4uJi8cD2BAOrN3JSof2ttTJtcY7Ap\/8AS1uuiaOgqQ2otJ6NfIsJsqZMKLKHtkaJ9Scf0eUzRPBAF2Zivt69uWyH7SgddsAkrrIi+kRTj7NBnsfdlK1VP47tZf\/37nHrPrHa7VL3NVJ7CIr2QXVYZSztEVegwcsN+pYLgnVC8zj16IgicHoMb3n8I4UzZ7nYnUuzt6UxOtSf3B2DsdbUSAydv8P6aWDqIXw\/BknR8ScMY7TMakkgz4CI4s6Wy+VTinf4aqM4C0jBkEJdSGdp4olP6DfRlrZ4brQnIuVJmgFpkPVNiF1dPRR4LJiN02qhkYmAX5gzv6c30yXP4ujAoSpf46EcZrsa2CtRB+zXf07Kl8o4Jpv0lq+qj4d7Dh751N+H6ubS1Lf+V2J6cWnOHMGpaOyEvyI9ykJroH2ejqFxbuk2QZ2PL7T8eSJ+NxxO3tMhX3Gvt0tzl4wDG3it09BU++3rLEl4obWms4kq0QbI3c+LXF9Ouzo0NKHmj8dz8OGnfQ02CO3lUDzKsTDIdwSVepGGqLp+A9cZZ\/iVynp9\/yTD\/GaySV0GmAWHvwOvMsdJzPURunvj\/KwrwYuElQ\/HHmsBkQH8LhOiHD5849FCTczt6oyn\/mdRya1\/hU\/LismikT+4jb+Tl1GYRb74U6tPNErPliAuflGOHUOd+9JFed2EjKKpRycdAx1mKz0z3nG3HSjHmUKz18ym04HAeOaZstLB54gXIP52zUPn67n8Hv3DDpMnKfvbjR8mEkq5fSJXWiFcLVL25TW3fGWCbOEgL\/zC1xP2iOOMdh+wiqQ17Vx45KESgrpZp+Wu78ccGRm8dwirb2XtkixmHIwbcEfTzCLzRD9rY7jHBouqIfe7jyH9iRaicNTCpcBGclHWXoy8wZfeow3AGUomv9S+RJTljk9G32gnaea4ILTYO6qPqdY9gkY4Rewlz\/U68zk2wJWXXYxm+2z+290aTKW8Ong26gWD7mC06Sn0RKDk9JUXPX57myOlI+guQU8+zu8Kk2RgaA9Gor1F\/xgxBY+n8WPN877xy8fZk2+8U\/OMxfdYu3BGI\/rWN8gl+pTUFapTf4Y9l\/w34HA\/2Izawm6eA6uSaUUqykzjkf1DxMXoXHdPq58y8XwxHVSv5hF+pc3dhLtia5Z8ZPxgRom71sHeeIFKQNwzPwe96fC\/nIBkTAZvcYUC3e\/8mipdyZxvzTaGndKcxSjXN\/pZfUVtYFPZUhWSAnY9wgrSwo\/vLqkK8hlS3C665LHSzbXGrXx+krFUEBlPmAW9fCCr4rMbH8Hc0e+JF7mS6fBqQ5c1onXhRNLPZRcRW4N8NZxl8zL\/siBCN8PgXUNoY1VSRzOhUUtQxEsm9oV7hdVxmma13tput\/qYNFOZSju3Gm3IuwpUxrhRlTIHuG3CE8rvOBh+1oO0DVzfQRiQhGCJuUuy54ACHgjrXtXKg++vc4e\/65+g1qTMNW3pTAobByE37ccyxS\/1UGhV7IRZevX7gmJLvLW60PPFjtWTML9fN9RyvfCzPgE2ubdtXhrLoyDUVnOiajXTUN8NQr\/i2TjM\/r8etnkDKQudsTKhGcUkGwRg\/WE\/CcuxLreopqa+dbrZz8CE2HYsDVd\/ISDOpL6A33u5XeLRZPOt5UkcRQwqHMXMLohvf9urmf\/oDIvf2ZydYe7f8KfNeOkp5iiLxlrc7QKeSCvBRQw9OyG\/L8c4Byou0gcobyYq6TCcLk1Dbynw3CHAzJDB2Wt4NEVY39K+bQO5\/wxR7VcROPbKPsCJypzniX5LZdotk+7PN0pUde+4RI7m63ePRWVLlrREPs12vJWoL89h2AAugD50X3zcC+P2GJcbELAFO3oEkjRq4kNsKhG722XY2HNGhMFc8Zdank+N3hSeEhXjKfyAZnd8P5pTOj+\/ZTTAGK4LRm+QQUpBqzep48jsf7YK4iecZZBkMx3th1jD6wuEz\/RxIDfONC4Mh6U4Q3Y9yJG0vtl3RfPDi9Sw8VTwfa4JzqGrqawpfcXnXbY90b7hI3+mEwFW1D6Z\/OU78SZKdo4gnWps5jrjlVA65WE6ZXJ\/oMGlNutrdLE9yaOLASNsAsDz1r6YyQ8wCBXdFz\/0R0Hwufv76mQwthlHjvfnoIKXBI76ZSobFAeJcaC3XUcQY\/nUbZECe+3i3h63vIEcR5w8xEZr9bf6BmbdSC0ZTQrEG\/DDW1o4RU\/3dDMs0dzHLpver+y1WKKFPvwhBxO7bajoQhYwae7IuzucD9EeYociUSd+PR1rWUhN1pXxhw9zNN\/sNxLTzSYIqQxcD2iwN8LM0ZgvmQvGtjoCMts0tHxhGgxITo7TU9jHUNTm7argzJ58s7l2JpB02bC0zw5gI8vrZR3BDyDnlq5YcqpsHPHN2rl\/RAnu4+zYmvct4tn01X0nlSsWHHvuO13dOg41FGXF28HW8soCp9OXOFMhrmYixniUhA2jvM4kuLdur7x4dvI8ryoLRUGgVo\/j0sGdS+5C88uACQJmEbbh9sYTSwIr3DHypn12zjyOoATtfK+dfHGhdkily4qq3jk0SyhNUlUz7Dg3y7AG+J4rFEeYuV9h18sB4wtulqbVlVxmH12BdaB\/6\/rP6UzY+lti0QyCrsvu3DzFkwvG1FwNZ97EuLCJKkFzZzKV4Zw3p+WW\/O4skLuVIZhQcCc\/FHNWfXrMjugO3MSZDlmMTkt9uGcLcmh7aqXJOeN42Tvinp0L+9EqNyg8IB4mwCt0bov1\/2ergJsNZ4ts560FFpCU6yFucp6hLcjzc3WAgcm9PIEL\/U4nxiAVUHN9VdPFwdsFRBVtqa\/Gk6aiicRdo2wN9tLVEyNvpiO3bnxbOenpukST\/sNR2lkzPVirqQKizvgPtzctJFtqkZ0NXO2ui9zUxxmfXtJ5DUh0eevwQeq6PJdZ2UiNJ7FW3WOwXe73NGdgo+0fsxKQebcK\/cQr56OEoZgO0i+q3xlFEEIwVV57gofs7yaKJUZPxvtedHPibcr6Aa+tjQ2Py3cxfqc+awBKAno\/a0NwVhecnYpQbXr44V5EqiHt9LbSnhdfAe58jpgaeWPn2NEeOyh50HoSogIg84qh8nmpohgZ8GGuTasuqPocHA\/bBogrQPsOfp8IQGrvJ5rs2CiyQLujjioTytzpW0Fpcb0H3I3UrdejadkqzRharK0URsi2U2I51Rm6otb1tnzkesF7K+CHJ+TNYy5NbTwCn7J837zoMD0Er2bM5TtwKnfja\/b\/1bTQokvLdpLRZKNGZMFrB6AeaUltRkhw\/+9iqUl8OzmdgjQjVPGZ9DD9ynC0a2MpE\/Sv2PsbwBbm01RGZ7DP9Ph59dKKGj+t7vNQsjHRIS9pGN70sy3KFJmkWvARADglxb4Y2SynyRxy5jtatlKOMYZTJYk6JV40ses7U9P+DY+PuS5SydE09B1CiyNC\/tWdCp5XvGclNX5sYeiszVf2L4YBmWioOdgUzI1imi3doll2ME2CPMeFE2wVf8NLmyuX6sL4dIlq\/Ss8kMjlGmTTjJev3n0yzVFSjaoSNU7HKBtGsG7rsQrY\/3wHLpihS8NejJRqzGlGfJYQT24qsSaFvIkwxdrygkOe9rqD06KTN4UHSgLnu5Je8K8rVbR27V6LwEnELxSFmOBtLa2yiPNUmMIiFWj\/ZOOjdLqU1INl\/lsfYOUCF7UI\/wXRNHpCFzAxrCza0VqEB4rGd+nujMAG6n\/HwGBUfz8lzzojxI+c5L14bU9me+kYbenqLuQqLbjly4inysoUHvFJVFRsHhe8rU9fpnlEFgyNXQ3xoIDBmcmqygud+mA6MDfAsfTJp0eKnMljBhQYZxedoGoW69JxT3ihwnz1E8ld0mTNV9uixXZWD0VfPyZWYE2mDQ8HavauPEc2HIlf0MBiQSfk24WBr\/glu2SEEsH3g5koBcFDj7Dk6JZ\/UPatiqsC9zjtM\/UPT9q6eaJz0jGQwpD4aSyvLia7d6MvAonlnSHrQ9S5a5cSL6Ul\/on3itxS+AMxdGMbwFrMlQWkTsB\/sNHOyILIQ2c9UOglEsbhOnLtD9i5NTmwBIegePoZ8o+XLFH97LLw9edvmLGrMvB9stmfyG3GIqFrImTnLs5EgJ+UQjexXclQqm9EAbaCfFxFg8uv1Ey8CHLa7gzUialyb0EEGyEsjviPtKeDFV8ZpwFRUpi0UGAzfqewAOcWBJAgOjHgMckq5fV1aMHUiYTtyzhpSKstFTXnt2RJm6+O+ljoEnEtiOD+8FTqn8PPydlkYCBrO+UkC8u+7g4N7KYsdBy02t5DPeMRMEh5JV0GyLFc\/qg\/lmmhOiqcS4IbbQugDRauy4EyjKj64T+PbqDV1wnAaM3NfQwYIGJ2GAkh\/sbiGJI8\/rhh49qhFmjANUj5133yjm1\/dLjIv\/3XSb4w3Y8\/GkbBNhoZ8BRDUbf3PwzMzrhh9RHSZvVVU+XkEO4ZrWNAxii0qNR8Ctk+AoJyQ3G4B8AD4P2xPofBfK+UTmNggYN4P8MjZHyCDLJlwEphxjGc3H2cnVzvfcPpHT9r0al\/1SAo2xcgc\/Pvisu8DD\/HM8i1WZ0WGpICiRZJ+K9YO7JVXN0t5T2fR7pj2m43Qro0pKZ85Wh+iVKRBR1VkePndwlnNxiTGLcXx5jui6RfiAhNGCAJvnv35v7dll3YERrxr5ZCUAjvwUCd4TILoH6udM5kXvRwGq+ppQrxBIe1T2ZUbPFPRX1qL3634eLxW\/diHd8nHRfbarOorAoBDG9wjAu2qEb\/Il06+EZMCwFrW52Srryk9VQmXEyFjPrXN4Bj1CGdaLQphdIHoGv4vfIbjv2rX7UREPD2MNMwIe6Q8PBMYUYsQChn2PJ4Tl2dZmP4zhRcmjxXECNy5XaVv7SA7EI2Hye40sA0c50W9Hr240LLQSAampXkDbO5M+KR0EjbCOIiKlz6LDoqTi1NEhsNWHJ0dvEo8IABuggpbVqYMW1lCiwJDKY8LB7ybJLcscrferzYqfDLM5SiE7CuBwU45DKduZwVlF2shm4t7eIXwpGRZQZHt\/nrYPbi14KjTBUM6QVeP\/IGVQ71OrNUesxk3BWt3Zt5SJ1\/nta+q\/ThX4EVYsVl77aL\/ytMAypsLQSL+GjppFZOKnziloGuHT+PpHw9DOiiSm4EMXV0in08QrJzSJbEixHWz4JQriz4Nc13XIU+Q\/nwOtrBBL7OzbDY0UI8kDPcdBnVuifJA3B8Znsdvd6bBPwxLmBGdzVzwuNTvipoHaON4vBQDxq725C6wcug9miregBLQ9a8neBsjwkKUiHyndfGgdh8Id3jTRmEENRQkNeqK6WHcGuFS1C1K\/MM4D607pBu937YMh0FpEIBTZaMmP5iTvxhhCWpq\/ArhJtYegkscRjzs6CltdawGLKGnL7NLTQ3XSa\/NNDCyLMVT8elM\/jfCieJuKz7BQ4Np8HtdBkOPNeFMNaYuRJyUAaJbnutwmMmLrYiOzEj8Dag\/JOmKb0wOEEsgsoX5ql+3zLLSFxG\/ctumkmH3HgTN+5t\/RHACHETjKbFAxMplvL2vluPN\/MPM8hqv9kebOXryYmpZ6Dy85cNiMS6viyTM2bqDxNP98GPQ4XSQCd6amsrKys29uTyI0JekAcZziM4\/INpF8YTc7Cdy0MTF0DKDOIrO8q+24tnSRGhi8tKRurfyMQfXiOXY+adOObIASzOjUtSAjPiufBIVJ9u7b5wJVG\/50xDynyFuMIQ+zclQGP4L\/V24a7k9ft15\/wqFpREVYBX5WYSI9K9KsSoS01C7tjGXuX7KX1aVL3VxunF\/rHZKaN8obTjlFN1gZEGrbJSUExj9\/du5s46+u8cH5QufVL9WxTXwInxpCvilNIXrUoFehGRdSsz4IU\/w+GxLClpot7jga04+fOzvvDhVqQMfrJnCbwvwBj44hJshtE2eKVdAlkuWXd\/+trXLWSXpTlLp5GdechwXZflrLIpnP8b2bPt051MysnixkFWgMl0CWTdyFGi7zuZT7Yfitpb+l369HC7BqV9gUWqOyMA6ZhLSWjAwQkLx2gFUL6XQ3skf5\/cEkPnySS2wG11m2ZIV+fmbgK7yCHIFo6bRFB94PllsesfkXNYTGcgD4cRjyEo0g2yCsl1osbmlOB4An6nLsNYmJ\/WM\/roBvh1x9ZVsPPzqalka1ZB1HL8ZrfxPfAovG9HDVuqD22Os3GWaJRkDqZIWhAhp908dFUIlPnUNeePNBR9L\/1K+4OP10pPe+3pJkxc8QOh1wKsHMygmSEw\/nx7MTeP2OckeefhIhHI0I9URZmseyBDkG5Q7htE4aJyp3r19AEOO\/unS8xNRcMe7zQtvVa8OLf8lnF+55DELCtm9bLui5P\/UeIfB2zcc3gdXnj7bbPduHgx276i15ycNqN7fzm7k2GmfOFPrcGY+erwIheXQLm8i\/YO7od2nmAbMpNYh8\/H2KRUK+z1IOnf659\/QKG7Rl1W+5I9PzawlinFsoQME8NvjrIJSJP28ffYE4hUo8V1Jtc05BEEMISAhXsO+zVcATkOhTQ6hJAcW+gtNiixBowQTE\/nn4T4DjQ7AcdSiAlo7YaMMyig+ZU14xi\/M8zYAbZThR2IsfDvt\/IBOKQUAYStrTbBT5ZU\/711ZmIqSCUewLuEyenpiFdKNWA2qjEApYLGgiMKOgJ8usfdt+Kf4UvUJbfwaeRWCUq5WLCK12f8KkZlUlQQ71bYP+lmWH+97Bo23Rsq1GQqvWdPpmZJkEpKZghfVUtmn3HMqa7AAA33YlA4REL8r2n5d3krQlhjICli9\/LyCEjjHtPuZv1QaGR4OCuRQD2GQqy8naxqT6dOmUXsXa3PUxlaPm7VShu\/xH+dcmFZ9qqaRD0HLXDQA8BU7VvlJbzXJ8S9f7j5GQh+O\/OdfMz\/E\/BNORBv+fwmy0O\/TYlzTgUwoJFAiJ2nQFYiepE1ebukulueU0nAe+Gkw2BaIlcETpHnK50aMFnwCndXBZJZmyiA8Q0t3hUjPvqQ26hVCjRhFzMhzR\/AMeNGTYPqWxQrMDphVnB9Iil816rxm\/uF8DmL8bqjAz8GDWiDAPDwcuvb10YDDqvuSbXAc3\/bvoLmi\/zslSjIiASL0FpvjrIT5bLXjnJr4SBE\/TfSYQE0YHrKh30UYeev98sinfQtzZC5osiS+ae7od2p8rgaHx16MDU1qxPPcU17v9a+5hTUC5n4\/ggDlfcVTpKeEEXkiqw5049EbInF\/5zys9ceO4Pb6A9wYHzUUK2eJ1ef95dwPQFytD0k8IBTgf03zR24v0in7wJxXE7srOdl4\/Xe1UTmbi\/A7ACvtffMp8cB+cifAym\/fpWaAGanPdAxvdQQgB4HFNZnHXmQMT6CQPOXYv5iSxKw7fAzq1bZXAP59gJ+3muZEu4MMIr2KMOobnefhjco\/3\/7ONM8HVcFgbm4U6lTC6jLGMJUUaIpqb9DS70kEpdPd0WxOWTWJSjKgqkmxbrCD0\/4vGAFrRjbULjhBW4rPKyxsngtO6nUebS4FZw+y+8JppDru9O7OtYnyfdxIb5yDLzkSuMJSMIwx89mN5kdWTF3vba58itu2ZsTVu4jaIVEK1w50ogW+qR48A9DmV7\/cMjBmjvvZusqqCrnsFpkyG0UyuNwjycBhgw2Ts4PLAzADWBvN6BLJQNE4ModH8pYwr3dyDS02X3gi95gdJWDh+SUqJq11TqVJ9Qs1Hnbpq+NtGqX9AD6bGyRdPJkxuldYs3PC5lLjX0IU+AnK1KwapGfMgwVhEv\/D2wFkALjX0EiNP7Ipgo6PwmJpFVE8E4fJNsBbuE6sY1f2ReLLg8w6kpARHRkBtdS\/6a3HAbfoy6QthKXmEOlXpdjwBue7s5DvwMVBtC5M5K5k1YvK7to5mN79TMEyXS2k6ViGLjgypWhKGcXAw5QTPO8vB4HcV\/4CgTcIQkZ+z9fxEnWzdw\/mV\/TwNWA3Gf5wBAa1FXopSY5rgBDN76kghNf0W6ZHpkxPdrXthJIF1LzXDBmdPAv\/Npe4tbDAllSGvlAO28Lr28LQ4PBfAuzwGOlcdGLQTAU9V1+1LgRHD6v+lgxUNchIAudRF+S\/hywU+A564f+BVhLuAgNvdNlarBEBBGzKhCXiRLcs6Z08cTXIk13cWPH5PsQ5GBLK5LWSDv4zElea1OXiYhuU8W62FLq0PUw0cC3BrQTv0kEIH6siawObqbgZ7M10S35DREN3D15nVDAazrDGzL\/oCNpMUSop0WSPHJlcMHXLTWiFzJbo5pa0Bc9l8dbqJXVs3nA5YF7kUrDkU1x\/Tbsy9osiMwdcmg2B06V1ZBfqrRrWJ+pCbnToMa379cuOOaCwrF34U7n8sNmLyEcNWPc6KHhW+oT7ra+YfK1FOIz1GA1DqvZSHz3FDFMGCJ69BOHTOFjhqCIRVIOT8o9x9ze5J2L9FiYIDyghMCBdl9t6I9ZfDnnnlnpqiR\/yvTm5s3ibf\/Znfi5geRPOvbc+ZQd1Uf+nHFCz03VZb445abuLtUPKjgONpz5tmZcRuLySf8My1fA5f2VIBm0gnXHnvyaSdHgKEabSC5o140km4L0Huxw\/ILGOPgwNmTLa39T4u\/EBxM6h32MuYihkJ7i7QHlt\/\/MxstgSir1gaM8QPImpjPITEyVo+XCyeh61wFywSPzoEVu97YBTGEcgnDcI+XHUjK7j1keSjOAdhxSaZ0mBlvYg7ww9qGhkJhj06ufcxy1XbckoqAslGtul92q96RcxkOMUE9FfmE5UutwWjZhvDMrQ4Xo9szHGUxhTsos2VTGzGVHSkLFgsEdz3V2NGG3QxwymG0sc27SrfiqCY0fb7U8KynaqxSlZEcKbusxnrRS9w\/w21O5W2bRKSH2ZjRuRJeprCdmnc25er4r3+2WdxwTSCmPc8uaV77c2Kn6zh2TIK\/rDKljrANIPCRBtheS9k1yNKw8rEw7XNzCztZuGFWT3Srv4Ezfj\/jeGNbCLp8E8adbdaw2hiFAqid0g4stLSoGodsm3hPj6nz4CWUIP8KPKeVwJVMWTwlfiCXcKAJMV5i6mVtgbSf49e9YSAZZ2hfQqJ2tBpJVRMoPf7SipirIsb7ceyypeAl4lipsWZFSkHZNQLZ6vdPVnLIKEJF2CWQpMKt3M5u0ayMO1tdLqGrBBgawFcAarMao7nsSqOv9iKx+NM2vS6mshqN1ccZCSbbKgUym94aMVKNNdfyQPnTHljjfmcd9oBQcmRpChkAvSGRrVON3HPv66rQwtyuvwJFyMGs2T\/Pa5CggqR2DkALinkVUKsPxhrk4WkffskToFC47zP+VtBih+cwpt7ndweb89grAQgevTC8hlxsA3PNgJ+BSfZXKk52nvT2eyTzlpvE389wk570wvAu5VcZsvxRgEYGiYLdCKVxiQq54+I9kLOQbUBrAfmuxUJ3yjp1AfxcSB\/Wqgew9y0yTzP7oIK9Kq4fPNlk62qUA05FB4L1FXVPii41VrVB\/p0uZezMn13yCilgfXCZScqZhW5Ly9CFu+Xn8WCoSAIj3NRnqe9JrgOJlHNRVzR22ZjJTXe9Qrbc6R+DdRkeV\/fdEB+eBrQWpxayLPIYQshk8aPgvCwezs5+ta2R3QpOdDz7WGlzrUYwnk\/91itXpi6kQmtM+OU11fkKBKhf7owJyNsWK7K16DCqukVxVHuO205noeyXRSPGnMD4RxK6J+XCvy8MzuIabpWYCC8shTpRn3jRqTySGAUd4uono3uO7sx+E6VO+0e4TXd2n5s3QfyZFrdnzf4kMWFXcELTrqPfq220K9fkzv0kuu2K9ig+NLdOsnLDLL4UIGPBJlOXE5BB3iwBXTME7uj1PXS0PNvCfp2CFB6w5WYoSbE8LwIOXabHI2W2RS5mjIFS6Gs0QCvKcs4XEc68E7Ia\/0lu\/wayiLT6OB\/tbC5XspJRso1gH4hblcCoztWz2MXGJBXShgu9qVXLUBaQDZvzHpT1dDPJZBMeMyGtNfSkXTBKsT6VKlwJMySFSVlIc9Vc9wKfzxEBEP2WBfVo4JN1l4d5RTLKJiKLsh77BaqoVEXW707txFvVpewbeZRruWGws2AmVOQzLPVWh7IM8o1kF19X9hUchdFYwfE6VIOR7B6\/aaybF+r+yUnXdJlOHlhFrQ7rY3WchaDB4AdS+WoxBxJ67w0qaZnf7c3P4LysAeVVA7cq1GGw\/4p1wZytw0oO0uFHbOu+4wx4S8Y7qrNCe5OaZZ8982nqea8z\/LQlQ8PVWSHJOsCUmF7cORWQioRUwWtyZL9trWvkalS+LbN9Av9325qnMPec0b+253ElDueOd3YgK6PHCBSJI8hQg7hQRddwrRXQO8SQcer5G3c1vPXRIYRI4zWXOWVqfNqImTXeibg7VbOCtJgef75uP+nK\/PkpCsidTdejjaFWp5Qq0MKZn3jADH+H+GkT40+BC00ZuvR+qi5aERKo5ASkTXPmCS\/fqfGSUxDC3wXRLCshDPAk1TFck\/gOxJLx\/unmQYKCG40QIFv5lh3h0FOJVFYOPVwqrOtBLHE+CDr4exWIklBYEdf1h6wve24bOpFwII+kWbRm568Wa4u\/qhH0EzLDSMCQHl4dEAT7vvi5+kyp0VmdCU33FFhV7+QUVwbt1n5PgnzX98ZGGqgCUEzNSnk+gVg3uGE\/rw\/E3mO7eC7k\/m5HEyI4IAqaasUHSA+rVzYg+\/s6x2rfyX7YOT0GIml85Hu6cwqgpBg4BIRvEaZ3MNyWnxhaCRL9eLVXIKMVjvxV8AaxUvpt2wJJtflNoq00RTH4wSOC5IElHhxUqn50Xhjscz\/74jqtihJy96APJ+wNGAmLwT6nwx939INe9RssDPSpWrEN2pvAwbAk3nFkSNk3Z7A17LSzP\/dXCUehauEnZzPsYtaUPF4p3YYzp0Z4nr\/xPy8l3cEfyY6ojwDTL3K9T\/EzHt5oVnAgwHzTxG\/Ob6H+Cau+2cQiSYxdPInmZyrEtamVDCYnYDO9AiCRrDzrI5xS3HE\/9acKfCaLUrZ3H1RHwDwoJIfaOPl5mlcRgmIy3Qll\/bfL+ErM8\/i15KxOygnYHH2m1wGFbn1s8CmwExkfX3r2Znr9zdR9eqzHDr3ePd1bDI7VrGXVd+Saor60NQBo6ebWmgV3Y\/xtEK7j\/lgyBnIvsfJ3r6YxLN6idpQ3zgUWD5AfO0VWaqRKFxlOFX\/dZboMPlH6B2RnFR4s2tDfjTUlMjgCQBkzDwIPzh1IiPseAoMY0VYjFCL8xitCM4x5owT+mY4GTwc0gER4toJrAcL89iqiEUu5n3q6BaChQa8fMPssuqJpoyIs7zqRS2PsRkiEiWH\/x4uuuvqhlTToFrNt7o7FjoybA5poIRC5zPGKhyV9TF91N28YOzz2rdHwVRrC69FSo6NRUanvRDSqNn932lVsjYphmgGWOiN8PZ56nfZPHeXR87hZ\/OAdSSD+KB5\/cT2irwKpeoAJy\/\/+WD5xHEozRDqbqjUd\/b6NaKW9fWky1qSSc4D44GLGPB1gfNrp7P8qQaeUJ3ZbMBRqbRlr00KYtILobfo0u7AHcBFg5RnjRUyx2WKq8+\/cXFdnd1YZen1BKgTjIcpJGcqvj2IndTx\/UrW8LhWQwPzURjx1jKgW55c8KpUIsGr2Swv8vJHBr21QuU9z00ugL4aA0kjo1hoiOcsIWHq8\/QNwzpdsWXyp\/uZ3rFn6b1hYPEAD+PWCndUYTWOGqnzOIH+6nxzdj7O49nh2VazCuPaSdQkLkvXjnOHFOIawCJMElsvgA7aOoAAbmVvaT7gJbBMXz\/hOeSr5zhqFC+IRuRMsNl4cyY3exMyLJeIjtCQCrBk3WjMafmgyVlnTTzaBmpGeJoOxZXvgAHcFZfG0VXgS4fOn6H31P7NF9pOIGm\/kj4jp7iUnn53QuQZE7+KGT3lDZimVGjbBiXxCrsBoFmS+KJzF5sEUQEFl9PQZcNqv6HT+owakrtr4MwFvVwmawnhT862IW9R2tcECF38RVb1fGQRfAcJroX7nqptowf9C6ptvzdrCbpm5fNooRonp6P6tWhPkPjXDubbRW3\/kjKBEa9I+lPe1Nk6jGLnLCTRg4hlFPkvfU\/FEm70B0XrEMLkJooHrbPYgl0DegcBjyPOLEtSt\/V\/+lrtAIQsM48UFiyQXz9H+G9AOnHdZbt\/oh8bvPXN\/hPBcppOvACViJV67oL1Aq8F3UDYLIkNA\/0h0+i141X8LIt7Rb9iKE","iv":"f445704509c31a1fb54fa191c40c88d1","s":"9135350d1cd44543"}

Face value and market value matter: Hermès' sea surf and fun scarf. Image credit: Hermès

Face value and market value matter: Hermès' sea surf and fun scarf. Image credit: Hermès

Pricing of jeans. Source: Various Web sites

Pricing of jeans. Source: Various Web sites Financial characteristics: Luxury versus mass

Financial characteristics: Luxury versus mass Methods to value brand names

Methods to value brand names Edward Hamilton

Edward Hamilton Chris Mellen

Chris Mellen