- About

- Subscribe Now

- New York,

May 24, 2011

By Pam Danziger

By Pam Danziger

Chapter 7: How Spending on Luxury Has Changed

Marketing success is selling more stuff to more people more often for more money more efficiently.

—Sergio Zyman

As Unity Marketing’s quarterly luxury tracking study has confirmed, as well as studies of consumer spending by American Express Publishing and its partner Harris Group, MasterCard’s SpendingPulse, and American Affluence Research Center all agree American consumers are spending more on luxury goods and services in 2010 compared with 2009 and 2008—the depths of the recession.

Unfortunately the media makes the most of the encouraging sound bites and doesn’t delve deeply into the underlying reality these studies show. Unity’s research clearly documents dramatic increases in luxury consumer spending, but the spending numbers are driven by dramatic increases among a very small portion of the market.

However, spending, as Sergio Zyman reminds us, is only one metric that measures marketing success. Getting more people to buy luxury more often is the challenge, and Unity Marketing’s data doesn’t show that happening yet.

Strong uptick in spending doesn’t tell the whole story.

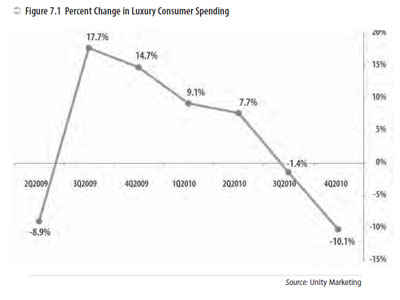

Spending on luxury goods and services rose dramatically, from an average of $21,909 per luxury consumer household in the first quarter of 2009 to $28,060 in the fourth quarter of 2010, a 28 percent increase.

However, in the last two quarters of 2010, the average amount spent by a luxury consumer declined from the previous quarter.

The quarter-by-quarter trajectory of spending increases has been steadily slowing since the third quarter 2009, suggesting that affluent consumers have released pent up demand for luxuries built up during the depths of the recession.

Figure 7.1: Percent Change in Luxury Consumer Spending

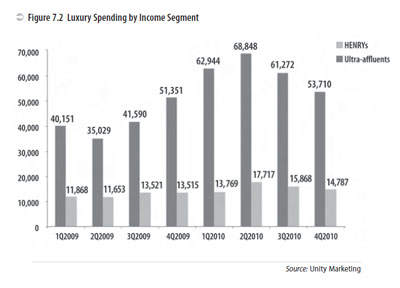

However, the increases in luxury consumer spending were primarily driven by increased outlays among the very small segment of ultra-affluents who typically spend three to four times more on luxury than the HENRY households.

These ultra-affluents, who represent only 2 percent of the total U.S. population and 10 percent of the top 20 percent of U.S. households by income, are major drivers of Unity’s spending statistics, as this segment represents one-third of the survey sample.

In statistical terms, the ultraaffluents are actually outliers, whose average or mean spending far exceeds the survey’s norm, defined by the median value, when all values are ordered from highest to lowest.

For example, in the fourth quarter 2010 luxury tracking survey, the average - i.e., mean - amount spent by all affluents surveyed (n = 1,237) was $28,060, four times higher than the survey’s median or mid-point, a mere $6,817.

Statistical averages or means are much more influenced by extremely high values in the survey.

A small group of ultra-affluents who bought $100,000+ automobiles and expensive luxury vacations in one quarter can drive the overall survey averages to astronomical levels.

When we chart luxury spending by the two income segments, we find that the lower-income HENRYs increased the average amount they spent on luxury by only $3,000 from the first quarter 2009 to the fourth quarter in 2010.

An overall 25 percent increase, but relatively modest when compared to the $13,50 increase in average amount spent by ultra-affluents in the same time period, a jump of 34 percent.

Figure 7.2: Luxury Spending by Income Segment

Consumer spending doesn’t measure the number of people actually buying luxury.

The big problem with focusing on luxury spending is that it doesn’t take into account how many people are actually buying luxury.

This measure of the number of people buying is called purchase incidence.

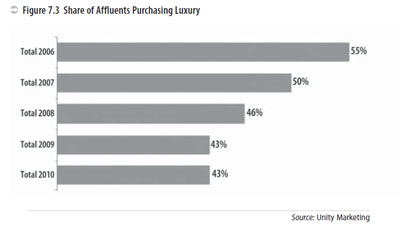

Since 2006 the actual percent making luxury purchases has been on a steady decline, from 55 percent of affluents in 2006 to 43 percent in both 2009 and 2010.

In other words, we have experienced a dramatic loss of customers in the luxury market since before the recession with no signs yet of an uptick in participation.

Even if those people who are currently buying are spending more money, there are now far fewer people in the luxury market than

before the recession.

Figure 7.3: Share of Affluents Purchasing Luxury

Given the trend in fewer customers willing to indulge in luxury purchases, marketers can’t rest on their laurels.

The economic messages are mixed, with fewer people with means being enticed to indulge in luxury spending.

Many affluents who have plenty of money have simply dropped out of the luxury market, gone back to buying mass, rather than class, because the value is just not there.

Premium mass brands like Banana Republic, Ann Taylor and Ann Taylor Loft, for example, offer affluent shoppers a value proposition that is compelling in the current climate.

They are being rewarded by the loyalty of ultra-affluent shoppers, who rank them as their most widely patronized fashion boutiques in 2010, ahead of such luxury brands as Chanel, Louis Vuitton, and Gucci.

getInspired: Vera Wang Manages Her Luxe Brand Through Multiple Channels and Categories

Our objective is to continue to grow our lifestyle-product offering and keep pace with the evolving needs of the consumer.

—Vera Wang

Among fashion designers, Vera Wang is one of many who have broadened their reach to all price ranges, from bargain basement with Kohl’s, mid-range through a new partnership with David’s Bridal, and super high end with bridal fashions for her celebrity clientele, notably Chelsea Clinton, Alicia Keys, and Hilary Duff.

What sets Vera Wang apart from other designers, most of whom have done limited low-end collections with single partners, is her determination to become a lifestyle brand, following in the footsteps of Ralph Lauren who moved out of the fashion sphere to play in a much bigger universe.

Estimates of the size of her company vary from $700 million, according to Wall Street Journal to $175 million from Women’s Wear Daily.

However big her enterprise is, it is only going to get larger in the years ahead as she continues to manage her brand to maximize sales across a growing range of products and retail channels.

Vera Wang launched her lifestyle brand from her platform as wedding designer to the stars.

She started her fashion company in 1990 and got her first big bridal commission dressing the future daughter-in-law of Ethel

Kennedy.

Since then she has maintained a high profile as designer to socialites and celebrities for bridal and red carpet occasions as well as designer to the Olympic skating athletes such as Michelle Kwan and Nancy Kerrigan. (Vera’s early training was in figure skating.)

From fashion bridal boutique to lifestyle brand was a leap, but one that Vera has managed strategically.

She accomplished it through licensing, first into perfume with Unilever, a logical expansion strategy for many fashion designers, then fine jewelry with Rosy Fine Blue, a partnership that has since ended.

The real innovation came when she created a two-pronged licensing strategy.

One was keyed to her core competency, fashion.

The other launched from the bridal platform to the bride’s married lifestyle, what Vera describes as “creating a lifestyle that goes beyond core bridal.”

For fashion the most noted license, and likely the one generating the most dollars, is Simply Vera Vera Wang.

This license, with discount retailer Kohl’s, reaches shoppers at 1,000 department stores and online at Kohls.com.

The Simply Vera Vera Wang line is envisioned as real fashion women can mix with higher-end pieces, not another low-end cheap-chic line.

She describes it on her website as, “For me, Simply Vera Vera Wang represents not just a fashion philosophy, but a vision about life and style.

It’s also a true expression of my own personal design vocabulary. This juxtaposition of ideas speaks to a modern sensibility that is fun, easy, and sophisticated.”

Mario Graso, president of Vera Wang Inc. explains the business side of the Kohl’s line, “It’s very interesting and very similar to luxury. It’s just quicker and the pieces are less expensive.

It’s a similar process. Kohl’s has taught Vera that a lower price point is not a compromise.”

Another high profile fashion license is a newly penned deal with David’s Bridal.

The company will maintain a clear line of demarcation between the David’s Bridal line of moderately priced bridal and bridesmaid’s gowns in the $600 to $1,400 range featured in its 300 stores, and the high-end luxe Vera Wang gowns that start at $2,000 and range to as much as $20,000.

So far, there is no evidence that her entrée into the discount and middle markets has in any way hurt her high-end business; rather it provides capital to keep the high end growing.

She plans to open a third boutique in Los Angeles in 2011 to attract more celebrity clientele.

This helps make up for the significant loss of bridal shops in Saks and Neiman Marcus closed because of the recession.

Her expansion into more moderate price ranges for fashion are pretty much by the book these days, following in the footsteps of Isaac Mizrahi, Michael Kors, and others.

What’s really noteworthy and inspirational is how she extended her bridal brand into the bride’s lifestyle.

Wang says “Our authoritative position in bridal and bridal registry has allowed us to leverage this [consumer] trust into a lifestyle brand.

The next logical step is to capitalize on our relationship with the client over the course of her life.

Our objective is to continue to grow our lifestyle-product offering and keep pace with the evolving needs of the consumer.”

The lifestyle branding includes a honeymoon suite at Honolulu’s Halekulani Hotel, decked out with other Vera Wang products developed under licensing partnerships including Waterford Wedgwood Royal Doulton tabletop and dinnerware, flatware, and gifts; William Arthur stationery, including wedding announcements, invitations, note cards, and stationery; a new high-end home fragrance and candle line with Next Fragrances; and Serta mattresses that can be paired with bedding produced under partnership

with Revman International.

As Vera explains, “Seventy percent of the mattress business is when [people] get married.”

Of course there are a number of dangers for any luxury brand to expand widely through licensing partnerships.

Shoddy products or inferior designs can wreak havoc on a brand’s reputation.

At least for now, Vera Wang has successfully avoided the pitfalls through careful selection of partner companies that have a dedication to quality.

The licensees highly value their partnership with Wang and are willing to work hard to keep it.

Testifying to Kohl’s commitment to Vera Wang, the company announced in its third quarter 2010 results that sales of its exclusive licensed products, the most important license being Wang’s, accounted for 48 percent of total corporate sales.

Kohl’s also expanded the license to include Vera Wang cosmetics in 2011.

Vera Wang is diligently hands-on with all her licensing partners.

She says, “I think my licensees have grown to depend on my participation, which is a challenge because I am one person.

But I do control those businesses carefully.

Each one of the businesses is different and I’ve had to come up to speed on all.

I’ve had to understand what the market will bear and yet I try not to let go of my own aesthetic.”

That aesthetic or design philosophy ultimately underlies the Vera Wang brand’s success, which Vera describes as “casualized couture.”

It’s Vera Wang’s casual luxury that resonates with consumers at the high-end or low, from functional housewares to fashion.

Copyrighted material © Pamela N. Danziger 2011. All rights reserved.

Putting the Luxe Back in Luxury

Paramount Market Publishing, 2011

Share your thoughts. Click here