By Milton Springut

On March 14, Swiss fashion giant Chanel filed suit against What Goes Around Comes Around (WGACA), a group of related companies that sells pre-used “vintage” luxury-brand bags and other accessories on its Web site and in five bricks-and-mortar stores located in expensive shopping districts around the country.

What is unusual about the suit is that Chanel is not claiming that WGACA’s items are not authentic. Rather, Chanel is asserting that WGACA uses the Chanel brand, promotional materials and promotional photos in a way that misleads consumers to believe that there is an association between it and WGACA, when in fact Chanel refused to enter into such an association.

Similar cases have been brought before.

What makes this case notable is that many of the activities that Chanel complains about involve social media and other 21st-century means of promotion. The case could be a landmark in drawing the line between permissible and impermissible uses of a brand by third parties.

Legal principles

As we have written before, trademark law differs from patent and copyright law in one basic way: its purpose is not to protect creativity, but to protect the right of a merchant or company to identify goods as its own, and to protect consumers from confusion and deception that one company’s goods are another’s.

Not all uses by a third party of a brand owner’s trademark are forbidden – only those that create a likelihood of confusion among consumers. Very simple – no confusion, no infringement.

What kind of confusion? Courts have recognized several kinds. The most basic is confusion as to who manufactures a product – a “Brand X” product is recognized as made by the company that owns the “Brand X” mark.

But another form of confusion is confusion as to association or sponsorship. A store or other retail outlet cannot use another’s trademark in a way that confuses or misleads consumers into believing the store is an authorized dealer, for example, or that its services – for example, repair services on the product – are authorized by the brand owner.

On the other hand, if the product truly emanates from the brand owner, then anyone is free to sell it, and is free to advertise the fact that it is selling Brand X product.

To summarize, the key legal principles that apply are:

- Anyone may sell genuine goods that bear a trademark. There is no requirement in United States law that the seller be authorized by the brand owner – even if the sales are not “authorized” they are perfectly legal.

- The seller may truthfully advertise that it sells authentic product of that brand, and use the brand’s trademarks to inform the public of such. If a store truly sells, say, genuine Gucci, Fendi and Prada items, it may say so in advertising.

- On the other hand, the seller may not use the marks or other symbols to falsely imply it is an authorized dealer of the brand.

- Nor may the seller falsely imply that its services related to the product are authorized. Thus a seller may say, for example, “we provide our own warranty on the product,” but not “covered by the manufacturer’s warranty” if that is not so.

As always, in trademark law consumer perception is paramount: what do consumers think when they see the seller using the mark?

In the Chanel case against WGACA, if consumers merely think that WGACA sells Chanel product, Chanel will lose. If they think WGACA is an authorized Chanel dealer or its services are authorized, Chanel will prevail.

Chanel's specific complaints

Chanel’s allegations focus mainly on three areas that WGACA engages in: its Web site, its social media postings and its authenticity letters:

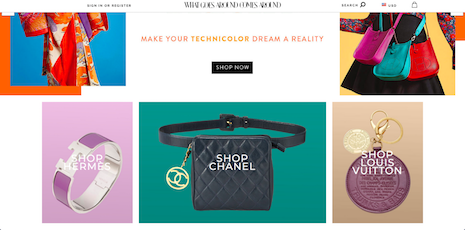

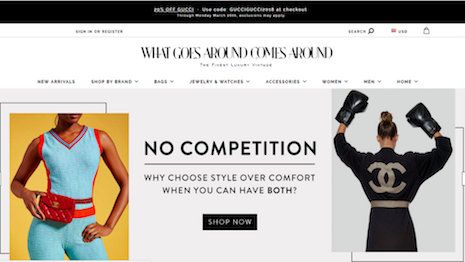

What Goes Around Comes Around Web site with Chanel vintage merchandise. Image credit: What Goes Around Comes Around

What Goes Around Comes Around Web site with Chanel vintage merchandise. Image credit: What Goes Around Comes Around

Chanel’s complaints about the WGACA Web site include:

- The Web site offers “scores” of secondhand Chanel products, making Chanel one of the most featured brands offered. “The mere volume of Chanel-branded products offered for sale on the WGACA Web site suggests to consumers that WGACA has a relationship with Chanel that enabled WGACA to accumulate such a significant inventory.”

- Although the Web site offers other brands such as Bottega Venata, Celine, Christian Dior, Fendi, Gucci, Hermes and Louis Vuitton, the “greatest number” of products are Chanel.

- The WGACA Web site promotes itself as “The Finest Luxury Vintage” and “the leading purveyor of authentic luxury vintage since 1993,” and has stated that “WGACA has internationally acclaimed collections of luxury houses such as Chanel …”

- Visitors to the site are never advised that WGACA is not affiliated with Chanel.

- The WGACA home page features a sale of Chanel-branded handbags, accessories, apparel and jewelry displaying Chanel’s famous CC Monogram trademark and Chanel’s iconic handbags.

- Chanel is listed first in the non-alphabetical list of brands, under the heading “Shop by Brand.” [This has changed since, and Chanel is now part of an alphabetized list.]

- The WGACA Web site makes “repeated and unnecessary use of Chanel’s famous trademarks, by including in the visual look and feel of the Web site Chanel-branded designs that are not offered for sale by WGACA and by posting images and content exclusively associated with Chanel.

Some of these complaints strike us as weak sauce. If Chanel is WGACA’s largest-selling item, it is entitled to show that on its Web site. But “excessive use” of Chanel’s trademarks and imagery – including of Chanel products that WGACA in fact does not offer – might well suggest an association with Chanel.

Social media posts

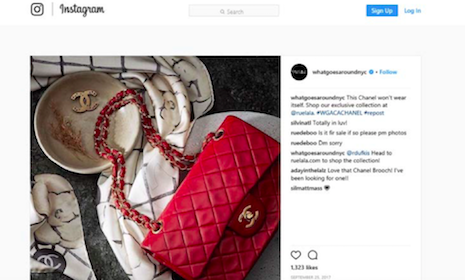

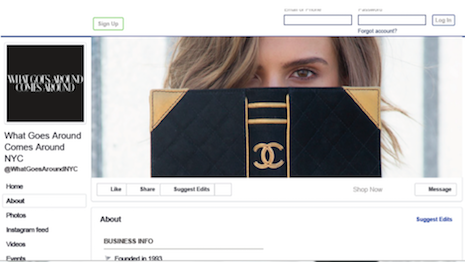

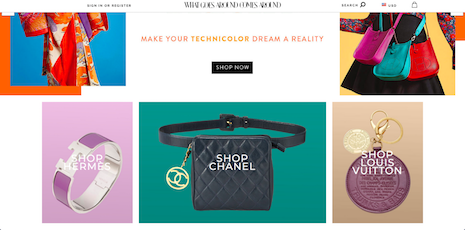

Chanel also complains about WGACA’s social media postings on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Tumblr:

- Use of phrases such as “WGACAChanel handbags in-store & online!,” “In honor of Coco Chanel’s 134th bday enjoy 20% off Chanel bags….#WGACACHANEL” and “Our rare #Chanel No. 5 perfume bottle bag now available.”

- Some of WGACA’s Instagram pages include photographs of models and influencers wearing or carrying Chanel handbags that clearly display Chanel’s famous CC monogram and photographs of Chanel’s iconic handbags.

- WGACA refers to secondhand Chanel products as “our #WGACACHANEL” or with the designation “#WGACACHANEL”.

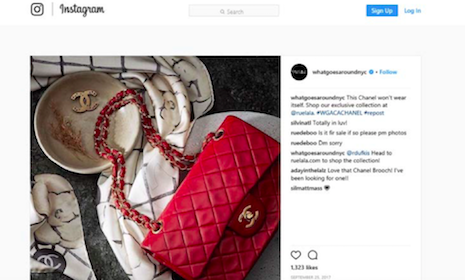

- One Instagram post featured the advertising copy: “This Chanel won’t wear itself. Shop our exclusive collection @ruelala. #WGACACHANEL #repost.”

- On Coco Chanel’s birthday, the “#WGACACHANEL” hashtag on Instagram featured an entry: “‘Simplicity is the keynote of all elegance.’ Celebrating @Chanelofficial & the woman who created my favorite quotes (and bags) on her birthday this week with @whatgoesaround nyc – they’re offering 20% - 30% off all Chanel until tomorrow! So major I had to share ♥ #WGACACHANEL #chanel.”

- Some of WGACA’s Instagram pages feature photographs from previous Chanel advertising campaigns, including those featuring famous models hired by Chanel.

There it is again: Chanel bag shown in What Goes Around Comes Around Instagram post. Image credit: What Goes Around Comes Around Instagram

There it is again: Chanel bag shown in What Goes Around Comes Around Instagram post. Image credit: What Goes Around Comes Around Instagram

The complaint adds several other examples of use of Chanel trademarks, photos of Chanel products with and without models, and various banners and hashtags incorporating the term Chanel.

WGACA clearly has made a major push to drum up excitement about its Chanel offerings using social media tools. But that is legitimate – as we discussed, it is entitled to advertise that it offers genuine Chanel products.

The question is whether consumers reviewing these social media posts take away a further message: that WGACA is associated or sponsored by Chanel.

In the traditional bricks-and-mortar world, prominent display of a brand logo in a store is often thought to imply some kind of sponsorship or authorized dealer status. How that carries over to the world of social media seems to be a new issue in trademark law.

The Chanel case thus seems to be treading new ground.

That's right, Chanel again: What Goes Around Comes Around Facebook post. Image credit: What Goes Around Comes Around Facebook

That's right, Chanel again: What Goes Around Comes Around Facebook post. Image credit: What Goes Around Comes Around Facebook

Letters of authenticity

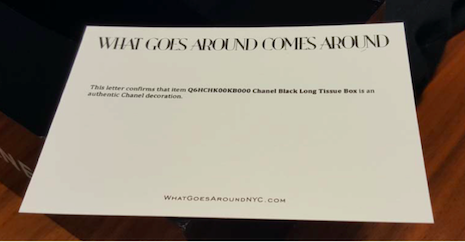

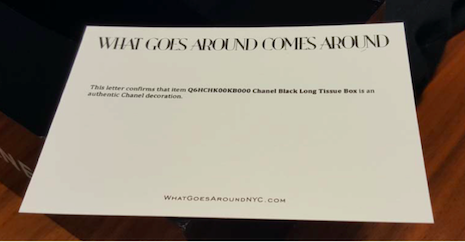

WGACA provides all customers with a letter of authenticity guaranteeing that the particular product is authentic.

Chanel complains that (1) the letter fails to advise that the authenticators are not trained by, nor affiliated with, Chanel in any way, nor that Chanel itself has not authenticated the item; and (2) on two occasions, WGACA has sold a counterfeit item (WGACA denies this); and, (3) the letter was used to authenticate a Chanel tissue box, but Chanel does not sell these items separately.

This again strikes us as weak sauce.

The “letter of authenticity” (a copy is attached to Chanel’s complaint) features WGACA’s mark twice very prominently. Otherwise, it merely states: “[t]his letter confirms that item Q6HCHK00KB000 Chanel Black Long Tissue Box is an authentic Chanel decoration.” It looks like this:

More in the letter than the spirit: What Goes Around Comes Around "Letter of Authenticity" for Chanel vintage product. Image credit: What Goes Around Comes Around

More in the letter than the spirit: What Goes Around Comes Around "Letter of Authenticity" for Chanel vintage product. Image credit: What Goes Around Comes Around

This “letter of authenticity” strikes us as rather contrived – it does not state what the basis is of the “confirmation” nor even what exactly that means. Is this a money-back guarantee? The certification of an expert?

Still, whatever it means exactly, if anything, it is difficult to imagine that a consumer would believe this is a guarantee or certification by Chanel, rather than by WGACA.

Again, WGACA is entitled to offer its own guarantee or warranty on its items, and it is hard to see what it could do differently to provide the same guarantee or certification without supposedly implying a connection to Chanel.

* * *

THE CHANEL CASE presents a traditional problem area in trademark law: how far can an unauthorized dealer in authentic branded goods go in using the brand’s trademarks to promote the branded products.

While the basic legal principles have long been set, it remains to be decided how those are applied in the digital world.

The Chanel case may well provide some guidelines for online merchants and brand owners on this topic.

Milton Springut is a partner at Springut Law PC

Milton Springut is a partner at Springut Law PC

Milton Springut is a partner at Springut Law PC, New York. Reach him at [email protected].

{"ct":"Kz\/GYJHMcN0scVikoreyjqYVucCX3X+usu3ba4NBUF6+PG9Zqwhl+\/60spJMZltlUdgbhOWTaANUqVj65UvLGFeH9W3UAcUCU9suHedzHHK0M3jKw6R28eXC9p9nQKQvtXJVm4udKMtQ0yOfJ4bKekjEMb9Hotn61n2cUBQJtoan6i0T0N1Qd7gki7Ns84HBbFKAK0tC4kZIfh0ufrUITNgRGj5AVu3Mk+sYZIat8WkSb8YlZXYqRPGr0L1OXI\/ss6Fxp2mF34j3sL4p4HxP7I1fk+SOBKaj+XD+Q\/ORLYg2VhcwFiKmFqlCjgJp6uJ5u6Wwi+NXwIXKvQfQdGMM2FXEOyP5jCoqjqPiyDZUkFYbq3RDzUR5M+q+PkY3d33MvPz+DJ7KX15OAFOQZQ9P87SIRMIqpSbFswX3kcvZ\/LGbH\/8q02i5\/1BNjmMXrRmiBhwphDWqmAk1O6f3W6IyO3hqMymY2SKhuQGuFT3GcgP0jcyagjM7FJiUGLqBLyJsfrfW14fyme4ngOBw1lZ5tkBqobsUw1lPIZ4YXHWd2QITQA3wfxvMjHg1hRc77\/f+JF7qx2bPh\/pN\/0iXlTj0OyAOOJCvrG41VtFo0GycyeFyDf2yPrdz+XBdKt4fWRo\/rwdkd1T7AicW0lChYIzDDZIO1+r\/RnC4O5c\/wnC67AWxrY57SVIhRk14H0BBsKCt11mlu4aMYX+1O8GfLqKlIlJQSAc9mAybkuresiPi5L9J8+vE\/J8\/6+e+UTOxBZO0SDFiXNRSTIDsGETnSAZ5njQfZ23hMzE5CrQdK6OVdjMdrFTOC2TQDBCyqPQeBKmd\/R8XxU90hTukHTF7jpDIL0nHvkgAAXyNliZmiGaup1\/vl2TFm6X5+EaUw4Ny7TbukfAaLLTqykLK6lwb3Ezw9e9K\/1XwR9jWAoGYBbgc0D+x0uQtVxmPL4DTpvdIC47o5eCD8BzIBTgkc1ULMXEDXzRDOsZ+QWkRQK9\/+NCxS\/4BqFNWhPZGeb4HdLcMsl0\/saae1JeBF3dVIuBUoCS+425gfyOaCW6YwIhRU8nHDOI16pkT2mAN4pYJ7+6TZI1mkn4lLCKCSu4wrBsFrRe4mSKPQwIhRSF9VCp4k83+o6lFFdNviDKug7AAhIWbdcKH7Efcr+qHdkiP28vZUEhC5aRUxxHuBAJwR0dmItalEKFZgzJ3ZpHnsuZ12hv\/yEvddYq\/NfQPAgSA8VM+G+wLkhaIAWh5+ps7S3s8VFfQ3LP5dpAK+1fPISR5RdTJOR\/NOIS2dRm0DgV1Hhrlq7JOwxnjI8Yo+cJ5KvLy+kAkiklUR4IirhDqtw8C8nLlDEIw8f5bUK1i406yefJP76Kts+5RlnVTLHx1\/ma7BqmRAc6NQmpsiqIkvZz6oPjmVyupAgaKQHvtlBI05DWcQtUXGlgBsOb3dsoKzzABnO4auWAN3CaqJsKFxwxoDPpTlC8iIEqGU4oHHP0CyNhfETH+F1Rw9Z31D0k0LjxamD6e60Hp1rzBiG13cO8c2X0UAyYixXtRCiNLtkGCuXX7tgg183qhBllabF4LTl3r+QIbU2UUGPywtF2rA2s2A5SwzJNhloSXLLnf+73kTnYzs+lKfJovDw3bG3OhqMc0sC922b0eygCu\/f\/j0XkOF\/VP0lUOqOYKWrfLLw2GqLqj9Jb3zdldHaHHCnt2iHTqSxMcPdm5M3gC\/5EhyAg6zLqdlOwYqx4tTyvHz0gWi92qZ3yTf6wpR9WngdJvMca9vdlo0opNO11KKkoFCOtXW2pVXtO5J4hJFn+9WAB6Kqz0qgOFekH3UIK1PMx9\/uY8nbqPeyuI0as4b7gQr\/\/5twRSE7OL1ZEVMVIbpq9UiLUi6EqyJaV14eLydJ7pW3j\/cbHr\/cwhfBJKgSCM53P8KletKhD5E02JV+izzED19BUkemtkiNSMRtGiceeYYW5b622UGCUOgedlL1bFGeTIV2DWNsX8nqJTaJ6Rir1OcKgLjXeVQy95v0I+bcySrQKmgsFLMZ7EZS5CxPVi3L6HGwimvLkSqlsQAWgQHFGsLCOTT1n9b\/7ytIidO29Tp5ivLLxHFiIaUrPmGngbHQpbfHEjXUWlg9DTxQDr5ulx5gYTFJP58o31W03NLk0EmH\/KGK\/RQoThlwLytfrTQs8XAvfU5nJfl+zRXtf4IGN\/5B4ArP0YE7II7cVJ8GHg3AkqXfGuHP\/oP\/a6BrqqZMRAm78zYbhJdtV9K2jZVsg+f4AZQNDh\/YKZ0Jhtdedkdrbb1zrdLQJemMVuzPuqIBtMRracKSX7iy6p3SuzjdfJafjois+\/1tB4KfMtqPX17p+ByKapdRR2Os7Q6NRGVoTkS20e1p3GQd3ZdpLyQxf+Kane\/T9PZGx6F0nmIH+BSEz4Bg0o5eOw8TE9HSU0aEZb9cFo2K8m\/ZEahvaE4xvP5zBhrbvZ6P3vUyFvnBY8pzpmEMJNeVvPf1sYYtz9rZfimJ7dFIvWR77nYAadeesAMAbP\/NtQd7YimLTgst8pWfr1CJ6vCTlZBVUjj8XV28Y8C18\/jnAosRq5Dwbp1DEUk3AA2nKW9CbP7Jmj1RSREgEFH3rKCGvfXo4zAWAt6107dxJ1qTMqfDjdBJKeedSjo19UZzeJ9FGE2EmBhKkQPd90Nyj6cfqc4iAChmCwTFe12+rjp9E9r27zwiG+ZbXV3wsAVCLXp108l0oH2ZcSVpIFjH0V3sMg0NCTRqbAKl0+k+wJfhQ6bJQNyZheqM8R1QL3KZ5OTNYkv\/yhd3r6FbIUM9rxo8wha3PIzeN\/1xryrKXk4WopnKI3X+8igVF5b9TQg2211BzTWO75ga9qcALSJOp4l\/XfWMwtodcBquef6qSAHyGgXoW1qkedRTkFcr8LpaLNvCms+U6JOLWEuqbTXWC9Jd1537+\/mUbPtBg0dNQhRzp9L7qNRq0H+y\/ExjvKWqWGcgWBf5G7OrTVbZ2cpJZ9h3GvbIcTgQZ3+yG83XrD80j85EA9jSnm+cyLyHMrZjxtrxzDk2Sqio6GH35WwYIL88GcBJ8Ah0LqjT87lKgRWZZ2U75s+mOCYa52OHXzD\/f70jO2jQ1+NAjJ586oFJvobVlBXUr8aiaKZ50wykboRAewA5Gc8iN7D45iTTnB89s4yBWwZrKfQLm1yhaWYs7cWJE3hEqOzC12Wvibbf8QdgC\/j2\/oFNR9i0wMn6zXDiwfDwyxRLD9buE1y1aKf7RwoQsvPzZrwNv0Ld98agjlvom3SiG6EwFTrUQSBldky1etEpIQhAt8jvK5sEE5K0o74ULzGb4S3lKlwpa7Up0+59qahoMmsuLoqyUVmyZcV7DyH+Ms7jUu4fIgjfWykOepkA4GkVMrVEY28w9ZEGfHqYMkEU8mo6EJ6MCIDpxxHGyti7KrH\/0aKvovYhANUOLNuDyQKy8gvvHZQTOVJzvh8KRScL87ETC6H94wYj+u7esS9V1GzmOTA3uZKIZJp5cax7KUPxhE8j6ttJbNr5TKUgWG8to5INMzNdkXbh7Uxa+jrwUHBjOCWPrG3L4nKUQ5b3RQ2ZfGCRdWhCpDgf6jW1BvpazZbEMJTqzzyMkKnXGSVJOn5CXKJpRVuFBo6C+RVjvgTAuTVFIwci\/wOi4552p9ANNN9z50ge5OFt0xW3mtkOvv2d2mqgW6k2veYQqe4YnoWl+4H3fl66LNznK5WsEzxAvWamZfDF2LD\/8g11M98A\/295INO7\/MWzxPeDUXEN5fN3u0yyeCWuCG2hNMRKK3phjdsCkp8hMMLlLPogt0iG1YxAFeOOWPhJEffHdd3EwT+JqUmTNyb2XRWCgn+n7IlBMi5Pwv6Fo0kt6+huaEhQysF2ywqqNWUYdhC2c1PozvYH3oDxVkDkVIz02v9I3xggi20eXIRBdYozEvRCzajGWCs9g\/gShY04KhvX\/DVI9Ue\/12VQ0Xx57iShwZsKVJaOfdMSy6anuM7rqRrS9zSWwUHxo1nB+K9IOCq1xvk8As1XkTAQjLRDGsU0X0h\/V9WItrTFTIeuO+nYcu91KIY\/ihRxv0QVPipk0N+KglwODVG6fG2M40trBvXiJ8gLXZmsZl2TFaQI1RNGYb344\/ZPdmWfj3U1ysCNWUJi3N27Py3bLE4ciexJO6ZC3QdBDQ5pVPw2\/XAAzFfMsPRJP6ANlxwelB+GpVj\/MmdTuzr9w6zbICjjX+DQmS8Oaq4iN9fv6tBwaGLgYnfGRjCM2B3nuH7Wxm4XpYN954MRERvyZxBWAhk\/3PgAlABnfDTFyRFO7moKjwaMUxZ7XqumaiG8hcUh8NmDKl\/QGHo1UC6HjMXxMXkSpT+g\/eTEGzXGshniOSz1+pAQQyx4tkpwAwBp35sbCAM71of3ycJNRqsNOWhqqRjrimrXoM+xxlFvOw1b+ihmj2W9SiL0\/hsOWQ7N68b7LQomGFi5dyukXo\/gdKOzqDcfGVVlCUPfQnZ8fHCx2l6ef3+A7yrv8Ak4GIy60stnVB7mMgIZZFdeBuUX4zCFrLWqDeU6zooGmRVd7OSQmgTJz52iihTqWoib2LnSyMgC3U9z0K5o4lvXsOUeAWJT+kGkXYnCzmn2Ik5UcGt9w2mh\/9ONcQVmhcOZYUacG+XquNJaaVuyVkrGkaQmj7vG6R7hO\/4dOURqibYEn8Y\/PqY3EOcmfCWtYClEHI6twnFCT8Ubn4rIoVtjdcPhHSiqbLArvEtb0N224IGU9HKFepedRCsDgjxo56DvPnVsW8ZniYCnzKnAxBTE+2dCHF6lQt4M8zUDErCIgcxr\/y+f7uy8kDaxdHcjEwnztwQvLzS8pt5MM9VuuyyBFRskvXrM4lgCqGKJEt48TCl9IwIpeearq4h9xzlJ6hB7n+OFbD6pyMClMwpZhIsLktPE0rVLQaInglbWAPiviBMi+QqC+1UVf4z7vjIIq3OZ7LGc9ctztKFQ8c+obvzH0FUnK+Jho0F6mdVUZ\/Uy5IWyk4t72JtrJwQOm+bthvsBUKU\/Ch+aOb0GtJD5\/72rOxBNb1\/Y+nb5NPnMv9\/EwLM+5L7S+rNCqGtuu+ZSxrZLAWEwQNr+4D9Ajv58c0suWjOVY4b4J\/l0RfTIvLtlOKKddDK3kI3WXwU9NrP+F+s\/\/Wm7YogagI2YyY75zDTFPz95TFt4KPppbnkK2zyE6HT0TV8jaJ9+5GionGQHUFoRRHUMqzX3BnAxSyMpM+8I8DhLD5+lEs0864X7x1ZGFmLCa5ZquZ+6cGZ78MDNWXWQQmZj3MxY2zBApCFPvGzyvspoL71ojPRIJo0UCKh36A9dTFMC7qeW0PHsVMC94+Q+UloaGVE4N7cHJO4EZCcbyoTgav6F22GeHZ6upxmJwStUwsBjrGTP58u8Ry+SWca1CCkr\/Bo1bSJYNfbSSY0zcf3j63HLl5w7ghfEE4rV+U0JU6AmwEA1jMY30zVJvFeEX2f3eaY\/P5ijoNeueGWmrzxdlR2Q3CJjvxoZwZpVytaeNR7HYttjSVJ2jD2froMIjNmDUuoIGfsPot\/Ed1dq254PnWOSvw2cSfTufehWjSyUjPGftj0BlFtsmWzjtPC5QMb6hOWDhjFPBtSEi8cectgI7nBGImf3OH6y1eEPBjgYrGfWRq+rdLJWC5S816G2Inj+qnoLkSHOy15vmKMxhA+qkjRzHydHBnXsTuOrEtNuoWgqbe8Kz8QtBbHPyZoKO9Fac\/cjXt4R1oRKFBANLaL6YS5NNsPdgFYHLsjUwuBvvM1uDzEqta3P\/ayAma6Cm4aY\/7\/I17ZEeAYAS0XZmv8p60gxfNCZFwTvaDeZKyNcb7hE8Sweiq9yU5jRlrbYgyNhg4ZJRG8sNckGrUes1m8vZVFe0R+7HX7lGSx9zZr4iHzYmU7NnTZdi8mlTYBRsqdZ0IoZaltxhocEhey6Qz2y1QW7egJLD0ZzE1fZjXNmjkcxbEpSJ9sVd6jTRBcn\/6nD7sBr9XvDDfF1Hh5O7mX+ar0M4fqlgBqN635z8htuBDaLadSkPNdL9VADcazp5JP9l\/0Ox\/RK\/C9sRLZhpMv\/3Y9\/TyFs22Y3iS26BbwStwHYKan2eoBhvsGMynkLDOJTKl488z4r8BnuWrId5AcCMMYVxVhZFa0JmBUkFltc00bjfImZd9U78fUOflBRnIJASHpqe6MA6oGxdLPD1Hj+5hyYBPEKPQiZrC11e\/PwjN2PfEd7gfy9I8ipFCVJZj2ogmb\/5Ht40Me\/rhMIsVJvA+ZKnjv7GjUz9Kf2ifc2l1ITvKaMy6CHCBrN49wRvgEUUpoyTAXSQsxE\/Duup29RlbXxDrnYldLFcJJspp4oRwyzvHjfrNAX+u0NX6DgS20uqbWkq3XkINopHalC+v3lV3yBljjPwTdev1xVcx\/dBu9VzdKeNmToOn7Z7Py4BTb6TyWPMU9GF13wLx3wx0DElTsY5wciW3n2TlHZPUj0dyUB9CK53QcL9IOeqXk3ojOlVEbH0TjjIS1GelWrHAWAejZjYqdxw9wTlIOo5JEWBNloTgsb953YnkN0hw\/SDs9iRNH54zSp3Io38+4VJJnxFPrf57NIqcd\/iiP2YTB7eATp69xR8pZPPz7wnwC9+C5qZun3hYDdFIovlp1yeVjVBlXDHZ\/pqmdlXLDe981wPZyjuKzzkbm+Rm+hzI8zuOLhJIuJAHpSimPJ8LPWxtbJw+tEQW7zGuDarUDD+cqtzwqD7ifsbM\/m0PR81n\/6ik15ya29qhliYkwP+nmPbNVJn0RB0sIc8Zeeh\/+Ge0EqXPTDL0UyWvnKJf+HDwob4QJuqqPUkC8NXVSNd+HIlmKP\/gur7EGVzo0Z6YSd5j++sBE08amjwckDWgzwxQPNfLVswD3F49QfswtmXPPUUO0TAlNloznkEtCG7cCXTIxYfo0XE0qTMQeC7os0TVgHpI9zRhopKbssthuVM97Z33vfrIMsr5rDaA9jJH8rWm8514q2HI67hziF7tDYhZLFuKtaLoPxwAbYWYyNQhC8LwSr1d6GYCBfPtzu3ZaFLjqiShN+ymk7cKx3DN7qVN5Q6y9124RD98WZIql23PMmYXN\/iCe2Gj09B9PQM0s\/MrRKku7K92T0e47xvSFFR8s+o9BtxLLTZbKi+e4\/oitWAXKZTpcYt5rP6lSaxdUBby7BcT1DHybgbqLEuB3xCn3kGNUYJBJ7MgO7eK1VDGzlge5M9dfUE4vd9tH6qTkBabZV6me5LibtucmXM1ceBpodORHsJ6P\/43PzVztt5XSDDgPiAcKPYKGpL33D5yOk9YFF0e2cbPkSamKa57Vh7T0TgvXMSxFqJwHSTngnUptcyS+nlLGUrcrbJg3FyeEF\/kfC3G7KpPHrBRlIaEraF4gJLJzI2T4foav+RgOiVNIgPRlD\/dxR2wgKAa6Vbbr9hxd6+aXFj0iaMoExKnqavge43\/9ZmCQ7z5vOeNt92Cq\/IyYPA9PCIn5TUw5aBoTdWNgz+TR1ZqiMsV5UMCIkSJgXLgrg1HCOu5JwnnSV\/mRj3T7OcdXS9BFlMyL99jFcc+FmUxSIlqjolseeR4W3j+Xa\/tLXqRxMq0MLRgcWdEC4\/OWlfrdEVT23i93WAKo90RfTCqV5vxQ1mP5AuR2xmmajVsHMwS3xAE\/QuT0nlOZKgpr+zBfeBrrV7EM6lpAIlEBjKdDE5V53Q2zW1bTJKULCa7bqDLqzdJrQduT9Zchac4qqirfIltPKA8e4A9kPPzv3rnC9CG313VfmVgWZPmkY5T8OaxA6eVStULf0JBNNK9AZAQaBIQS\/VX+QmeqPNKWEyLAzZ+Tg+rP6Lz2rOitTLnGXj4pyqAkd78PONXNj6TH1TOxZGOKPRHkf3YY\/tkhgLuVOx6on8DcVtegnOcDXkd2OOjZ1ry+pFBYJT02nSJJrIKv8yBNz3mg32UOGM\/1Qf95KeivKKwBib7euueiesaq8ExAVv9u+VJ4783mYI9WdW88j9naHAqvGtXl+RSkGGKsSR+rEch4DEAW2wB3scTnGvLVy+zBE8lO4qnzYZ7VIGaTQflvcayiYpQr2N79bb7A9wD35Q7UB3VDBtNYTC\/NqdwtGEM48oZvHY2whEFw2zGHTP1+06MuVQunPdTAVeFdY3YVa8U1aLbQ\/7Lo9W7sliMJ8dAkcsGsF1JlfFoJcx3qsVuxhnx8pkkhoHVwsvXn\/mUewxLjs7j3DmrqbhBmHcUFRtcK06vqZbBVfODQfSklufEdqTwe\/XO50sY9rPAI93OLQF+9\/anHec83YAeaEYZBQbpWlbNGRewHL45jCcNgwmrfF3xVxXG6vJ38tUPre3uvKNxuoOV3SVKNCPtXHD2cOS7I6TpqqpSIfzyd9w+5NIf5xo8tCMh4HG4l+H7W8yXo15EQlNclgiueb\/RWIiJYK+zsxNRZ1ojnwkP\/HK9Rxrt1Tsd1RyxJelDOT0XOsaX5cPEGBuUMT4rj0ngkhmlGscI1PySt40p0yzGh0PPHTyFuUTML+CSK2d0I922YRhg0LcTykkm3C+albuXUp\/HhfDao8h2Gd1J0Ab1t04HM+kay1esnow2QXcFIPeE7cZ3RrvPfrOp1B2RxfyuL\/4OLYulm8wG\/UHqdsdWElacbRLxDB\/Iy2YVTq\/ym6LQ4mE0RJlDxhTfnAKDsbrt8u80rkA3V3AgG9P32Ac81O03QOMGydzBitjvM3eDG5VR3h+zGWLP\/LJ8NFXmNoUZxVCc9XOse2IEFTeb6MX4ztKCQJJ4GmNrRI\/ZSkRtrRXnUeEkOTeojO7mvZFRvoWNPxnjx+7Hoy+jBkuOQ9fRmY\/AB0xPK6u4\/l3YOn28OCDO98waSy6kpqkY6QfvnuVPOWTbZR565S61qS1nf6Ysj00wurF\/gFgv52JzroJTGig04I3DHmIRTFh4INqErCLcbc7dgPd0rO3S5MA97H6lEcDP+KJtxi4ggdckIR4Xzov5L+JlSquTPXHN1qx4VhWyzLtriHbh3TlscDVKprRgYjL1RnUopF5qsdsKdJfSNXG0k5unZBTHYTvsnmcM7EqFRz\/W\/h5XiLOy6r0lsRcTfKJ8Lgr0PvduRSoogF9Y3xb\/o3jcZwQig6vJezS2fAocDmjwoRTuw0c6k0KIJz7g4EcZlYJSVuzae4UYFRMFJRoeBDnKavSZd3Hq4syNPUnYNLs\/uc1T6d3rO6IpUl2blNWxyHC70zfP6xOHV5V826WCSI0Y84dLI5AVrujg3gm7sdwXx4ZQu1uvprbp1cqb7Fk8T9ovcb7dUhWOrlr9cMhSPFkbXh20\/eKB0BkuCDxh2IWBebi8TbgDOKH8XPphYg3hv5JDglaBVRervSfG86Ay+tLPIomz8OAaj2QhF+KSJrvGnYVZq36RwIv\/7GkNQwrbsVBpMWbkmyFkYCIBOO+0NmGV4w8gnldMKnBKRHNh6fbRSrkak9vPAY\/hQl9NeyZrYdJ7DMcMlVqEoKpfDoE2ZlpyvNYTRhGJ7THf0ehZyGtVB6K67zOyMRIGkaG1tZUOXc23acLv+Il741xIHuYKMsTpxShmLRcs2KJCQGKytsbZ9Z49uKGFD6b7NHwatUR1OAYAfShTVZIyr2yymOcUH8PtLqaKSdwY76LRsOOBjMcuzmnz5lKi5evxaSEGf\/VBXVe8Gh6EqiHvgwVSSUZe6\/XRwpfskSo9wkWk1eQZ5V5MlrbOyC\/+fhct8JuI87hx5LRtmhCbfbjB2Vv6LPXAMH+mtMFNF6pWfniS8wt+XbnUdF3Y1ZvcBherqMTVAqwhq33GeBHKvM4fz9C0JtDbeikpLkuU9H1B5+V4g8xU5mibq32kHXQ8mf7AafkrlbHniZH1pWMoyRO6nSfeBwaePSOD5xJSLyLSXoQ6BKLFb\/LqhdSSes50TjctewaiYl6NqyI\/u5GxUqzxYIU4lOyLYYMruGI7uaDPoj9QxDxXj\/ZVHppo2RbxKK8ru\/ynhjKXNx5qXTMzb2nlJbsnalERJD9wzeVL65P3iHGKt3O45QjlqY42AzlBQ1x39aRsSTkCnp\/c7UF7M1eNu+KB9tK1U3\/9VJ\/bX5yE+Ax+RLkKcGEJ8gwEzK6SL8oEyb47wdxRwjGu1WWSpvmL+lHRvCbsmYM0480guI7bxc0LmDc0MPbSRG4cQSN63JDDdaXKizsqmLa7LX\/Szs\/X81HOwoHTx6LtAjg6zkQeYh1vHJZwHaDLHMxVLL7Gelzv6oIMJdhTjgZ8mnjpfju7MDJsbVrWz4zATfblSxkMP3MH0jV6BeDJ+Z\/UYnouAVRUOxOmu9W2iXQ0SPQS5744EZRDtkrdfTUueL5rUnHCdaNLY+7hS6LZIS\/WMrDVNCDtqF+VGPQUNZq2qMguKmY4V9DYMuuP3x690xI8hRtkBD3v+Ne8LxPOs\/GxRvVwzFuKJQycjfhHN5dXcA0hqkzvPj1Vg7zTDWJA\/Xzmq\/LX53TUNGze2zG4ae+4lxPq5a+RZV0qPnjjx6HfC4prw6J+WKI+c\/WaTXckJfkmW+8sAbfgJJBv4HZ6WwlKXbB\/DYbsnOkmeNZt0FW+siMtMz1dVQKnHKhDqOxTYOd7r8Bd4Im7mVSQmCoMbcrDYx2dRsnQ1O1lEMJrh6QSbI90D9GBv\/tBxpah+VyS+E3N9IkVhIMIv1FX7RMl+NohkLj3yPBrM3ccr7Utlg5TEU+h4FC876serXLE2RstK5yBvYHirjb6CW3Bl+BYsDK5g7wultKn4P++fl7wLm4GjTG5kFyIlG5ijohIXb8IZatx\/5Ou+amqaqXDEWhf1XHZDRonWgj3\/czdEd3FGE4BD9ssjkBkASY4OuRtoYfmw7HuhdW2i7KWWHl4ypyiiqqIRJd5wNx310qdEWAMb0xcxLO8R8tepD5MNALlNAKKsKtlxyiuFQmzQ25TZXKb7+qnYcXT4YvBvMB+ND\/56I6ysmb+Rv51KdK+y7XRBMg3f5NxVpT8QsLGTO9BqjfwvNEHgeGFbKApy7qZPndlvHe7STs+hARYxrGka7axsywpBdR8W0m+LTlTG+xDMQOAvN8lEMpcEiUdSlIAPM9M3vn5a9tJIAEmakaH1Q+VdBQioxKMspgU8HcHhB1apZfaZvrqfT9u5NtX5EELeGYbAMu04YKBoGEo7HCv\/PJswN6amOX5X4UiHyYEdXD695dbDyVqfF3CEy6yM70oTAop0gTMP2oWxYdT2sZKc+HGDWL0Q2ynvYNDPb\/4Wt0rK2c333c3Zp80LUAhy2yLjdYDLt\/eMP6Z3U4\/excgqnzrm1x6chi20J0p+rnxxbn6VTALyD2aLSYyG1gm9FeDIeU+9DPIEkTFZJ337ejKFtCJMqD256yH3ie4uWR8iBFu11iPbL8BGBlp3M9t7bwJgkEtN0wTtjlKq03Vc819Mvo4Nqat9dgkHUhJ0aErJWNhwMG6+9dOQrHEhL8ZZuTfTmdG1TJReoQR+cf5CV4lXOlKDD\/kPhnRaE4wewTP0OToeGvJMKK8X\/aGkVQcd0OQBo+R+65fsDmMxUfUnu25b8Ax9HaH1oOFNZ14To3QCTWk1USyrq4BprqWFo5SZxkLRoYR8vVj1tNVrvBrBPYTC26ODeGFvDrBX2XccluppoG8jP9D6+59OGXe4D9I3E7wiUpZSHdWpqhf+ekv4SO+cH0WsRLCGI2fm0lIZ8dl5+2GEv2HYzUVOiw4unh2D0M2xy53OR7IPmoruSD9jiaRytW5VKmWnhJZmmJ3cRsC9CDyzg6bHVUKhzTvuJ7JY6Tt0f1OcwgEjJXpjB4edEpALMIH1TL47ves4jDMfeWjlWrGSZvMhGCA1R7YMpCrWUyRDpMRxyClO9J2T\/A8wdXAU1eWB922tG03e7fgVfmeWrqXxPwZfJtUSuwb5nbJeFcFg\/Nlr5wekAxUOThWIiidJzCDG742hWFACc1lcoIzUj73L9D0XzEcIekNetpuEwCXhhaJ0+w5bbzDdggd\/TirVE8uGZSmJMNP3gilLDK8\/OKNUC\/40xa4d9vtQsw5Ta8Atga75f1uuj6DAqFL1dZ3ZVnnYpDcKv5CqzwHZ3uBbSYNwwJHoFN6i+BNq8ow2T9RItcAV5HMdOJ7eEQPGnDbCBNfyW3jcjQ+KrHyb9R4mt2itbdNwWFa7aMkQuDU8lqJer\/eAulRAi9CRb3LPJiCi7FPm3mC10eku6L91R4oAwKYLtY\/W2b1Nm+ZX06Ui\/pvsxQVNxZ1VH5EJhVDMPT4SGnTPnKlvuuPMkllYIwohz1LUgPEDhohgdm4Sl1\/VXNElejKBeHT6ixVx3pkW2xu+C911bbzDpkbkVM3kCsjELTJbeZTOanXPAUrRJWzolL6wUCDK6Y8BU46XV2DY7hnTlmSpHGGtTUjoOWOfTEXVi0\/Qt5hmMXvsk6TY+0AuKCdFTfqD\/sOmZzJpH48j1RYlmgaJTToV8XITIG3La0iEcjwQPOYw3Yc0IOsCKtz7T4\/FpBJsLMk4EIA7l+4B9zIdwUDgvmgwvqwO\/6lWRqf0Bh26VugYLP52HtSVQEunsQ7k74GPatDdi613V13WYDU4W1JERFw2D965gbOLzwtiDb2Ildv8IkwcV2I87IFGMJpBi5ApVntXqg1PYASHjMfMQc2lLOPNzbtWoYVBXqWWOIxCYS+E1Z0pinUCsOBYbYn3wj1tyP9vJtc580pnmuJ5X7hS1wGHaeephmMod+MUzf\/GXiGLk0FSDhgS66\/kJDZ2\/0lvk46kK46p2XBVv0STjE9YPUN+6n4TQbBwDJvs2SrDE3xCvEwqUnUPtSrf9vOejeYt9bJEqFmjYPgT\/Q8iHuVvs0tIr33pRv9oqKnccZ5wCzeMm\/L7Z56z0QafEwYnmUiflp4B6ibkJWhezwzH+FnzF60IZeX7Qinp3vMOlupTNMmZQpSsCsOEDPQRU5QtuHxJGVz3obBCH8l0sOfFETQ\/cqVw9sHopGG6opM+d+pKw1xT1TYdly38PCRyu0TmI8SoUcyyy9zqiHexXekRkcNuCWtO7Fp\/PUuIA5tONejAiBEwE6UHm\/ud16fpITEzBgF1XalRgRSMcyFgDAJwpum3W+FsCguPyhEqZPV+9\/t31zKevYqeULlOl\/68YEprZwNNwhOCKogAVBaRKKehASARZA7xwKgMQl2h+rA5aSPOjQZcoZn6LXUfQ8mT6\/btP7C+E0f6PPrcKYusY8Ydv+87Ddsy9YdYNO2lVQwoBfX24U9Gf1l3eTBpaTnr3HydgnalujAN+L9+j+Q3alAayQ1Zg3xld\/01wvfBmEU0pxQS6ApTuEXxmzpanv4GFSYDDrta\/JzCrYqU4WBQt1f3aN5TcdF6xuuk0rM9or85V+uU7LpVOsEgwCF+MH4voe86m8xDS10l3uQ+pVclrqyrA9\/OxDrd0CrqRD3C9nUFHlY29AKgukmJ\/nTRyvssvVvBOHMIfQrEL95mW+1U\/ajSbw4uRJ371bFXyUR22VW6kCSvv8OrQwNI8P19TJXwblaYS\/QjK4uuooqmQX9+ymDzh23BmHRNPV720wx8rEuIckArqymYeUz4H6fsRoyHPQvGvYsPvOKb\/lFFqrtYw2dLII+LJHL1RYKMj\/EptYr\/jmaj0j03DhqyDwgJPN1536Wl155XV\/3bDGueYohvVLhOLMOvnkOeR4qIiskr4f8feywYtQuExsky+Z8x3Z5HqGGd3+POJjAgmlPxU95Bma9CMrBt+fBQN9kYq5+ZqaxBIWvjMjaLGMrqVTlypkRYdy0qQAr09Wf1QSR4DlFQNDigpTB\/I5\/2lXK5BqPNKSJczLuQ6iSTIaiVlak20cnbTT+ZWWPgFeoMDWDrSrv0zhfOioEcebuPPoc\/nDs607e9k\/ijz07tsrR5WJk8vnQdYcea4RZ88WR3iWnmCJUVEk4hel1zlw7lM5MEc2rFiA9V1W9AW+Ep5agntyBzrxRHIY7zSvE9iEozEGNy8lMDQkSLCPXU6oA7L7x0+tVyFdvo6nirERQUWYicAT3FJkc\/m16UbYGZI9FHWs8nJYbzrEXWsvJR048RUDMjvweGeWGxaJfsF\/zec4YmXiS4seKWprWPxoNQ9QWPfdLqOtAhXDjtZd9snlPKtlMyz8XIUen6ZqyTWmelGvTaGN2ww7FjSMCAwPT2hBVC0HWngJOXX+A7cFsNIJRzN2tjQyn9ObsYzwRFyLEawWsf82eTcpXzOaxSAkAys1td8JSqeYjE4RqVdkI\/uG9gdpc572AKhKeKLDD7ywFlshgs0XZFmRFwFnemQSWf73LZvdFWXR+qxKiDgCd6cdnjj4DbhUs+poSerka8XZAn1g33GuxbzjIr9OBGZdFwWaJKwic9YAEjJtvUOa+z2o3xQ086pyEp\/zDARJDgUz+gIuJago1tHkGwbgSTw0qAqd5xyn4JA4GCne1nSY0+vtETNuYzP74bHxumyhrr\/sw3yWYFlQmsosaxFK7Ev14NiqcDNCIWYQqfJ3TEKT0e9DP7ZpP9oX51Yc\/VrEgpf0EZa5gVoYdqb84yvzgZDKGpxbJGtrOiBH3O3Pu8oz9VH8SbKHpmS7W7q1lWBRT9rP2cHhkvh47dkMnNuxPCioQ4kt8Ha1vGSRH8Nsfmjm05TL4xRKUJReWpc+nBRzemIKPZYmxYlo26IULoc1oCoL\/1Y3Zm9\/8JaK9IcCMVVUFMPIlk\/gp0cqE82gVkvAzj7v7cbh40jQ2RWQ0cuyFtkX2xZtI1FzGHnInuczAlnH+vJhHfohGGgoOlKVJdHItWn35HoQLNRtGihahnqtc\/ygOtpsHRK93CrhzLTSPYQmuZO\/yLdrC2ral8Za5NPl+ZjatjY\/1ryGUx2Pl7EpgFhnJv3cxiaULrEsdc40Rf\/VjQ5qT5o\/1fcuDfzyu+674WjP6mO3CLxNE\/8FpbkMIenH8Rvt+3KfgIvLxll39CMqtUvhKTHabXQ4bBDb1j\/zf9zDM7iu1AP4i6tAY7TMijQHlW0FGE6So2ulo6iIflF0iUfp7k92JK828yyr84N1iU9MBfsY3UV4Yi7iMTrhuZfdWi49E4pM4vGZmkSt8pdjbC9nCrlTMAz2U6tjQEma1MmJxyd+AhWhsUxL1gTKP7Tv0ZYuMxS5X3NAagzeRxq7RM1\/of9sGQqe1tebKLrZFJZqGNeIhGsF45dLoB+S9JJ1Iq4gqg2r1tOXjACBmiliWsKo6KS0IfVBbsjBXSObf7DTgmTJOu4ShAx+NYSzbBybo4yUMZtEss7UARROx6PSGSd5dyWFYB0QuaGOFAk91PkSodNGVDsKg89pbrRaJLLul8vViG\/Im4rNOtXgkqz1JKVfPcAHm0\/YtZgFMGBNbzxZLUX7Mch91U+qywVxqMiW5pSsElsIA4FWsVOIY89dRUsr9RGnb\/TrP5KO\/S0S\/BJyFkpJrp2fMuWFmbYCwp+Lf8fR\/Fg4LYUPGpATelEc2vGvJO5RPjCOy4w6Ji0stDmnkGMlLRHLvwN5WZskcXd0EWDhobWctFsyiRrohcCO7bSAwpGbS60CbidwarYVrzfYAXtXJecMgtOglhTYeqJbAtPiOLw9COS54Nb9tni1hpHRAckj+7FIMvb4bnvlo4HOqyykoEw4A302Zw3bLdqldpgVRjVnKoVJIo\/A2mUJibXszkTDdhpdV+IamcB3uGcL9WsJt50bnTLtR6WysD9me0qRSVzfK5IGQ8YT1xS5O5ztJUlGlSDIvuvFWT+Y5oD1dNr4sGlv+q+b952nkY8LA81rYI2r2E+1nkHqp\/Jh1fbZIRTMO7yP1jyaNtcwTjVxTdBo2MyvfEBH2j6F9kWtbM45In9vhfaSPSUrwh7AVJBVyqntQxulnc8tYBdVObrHq8\/1Gj+7jngy0k84vNNQvCUBqTaa\/yu4n2M39dODhYUnKWCH7hPwwijdm1WEW+EZOaBWXzcyewb1HkKx9y7pCnbj9fBUD4ZKKYA5NJHmvzSI61gAs\/095u4RI0o3zgGFEUHftvAojs1VJtcorRHOwsJW8XPDLJW5SQhJKedo5l25CjogWdgS1AV1YRWh6+LkkNSpfS+ppxsGnNYZAYJ8ZdvKnUnwF5qUcS839gH\/LO4fnLKrSlGe8rtnrx0nti6aD73KW5z5ITBjCx9R0gWhrT\/4uvFwDNKy3ujWWEj7fqETt1+lsq6ekUJwSFQxlqlzc2iQTw2wnfPszmrtDK6iUVBBEYmt\/4R09tzTa0P50T0t8dIMTyR++n5BZyzAk8NeLHPKOp8X+NbbE5vIQsLxYbe3zxChIRZChWNwWhJIav\/JsT81v3Mclp680vM0UnjsA+tWWU8CqMc4u8bGy5Grs16h0NxFdJu\/CPyfFZVvXsJZ3c+dYx1NkBgeDQWS3xPTF6jvB6DtbRljtPXliBq427Jhnwo02vUPM3Rjh7ghy33wSW65sNSbTBJfcm\/LYdS6WW4EimAfBVaURLUEzu76C1zJXw6cHPCayrElhvT78ehoj0dhwKdXvfV2EcGF08kp2Hx67IrglxW5iakeJENopMtYy4Lq1kAGjFbIKppNRFz8jNwd\/TrKd0SNlC00DFF5H1qPrbHIN+6\/z3q0xS2slNi2C+Ol9IpCcCQjHiss8KVVVc\/d\/DjMPPJiU43xu3+1LJYshoKE2mPB31RGhiiGxiUfczU+Vq9oUE39\/\/jhOU5JgS2ReS\/BUYELas+sR2UDcAZqSBB7hS4TY6Zrne3ACphKHcBzO6tA8ob3vFsYvVrURRyfzkYQBnopVwRgNkqHdP\/HGtrquMfDFobIUjkTZ0+baUMXPuPrVmvIOAeS4D6ytVyxyIhOhsp+1TXxQZqvYr262G2fRysB9qjXX6UNc0Y8zX27murobKhKBA6dr0Hlcb8GgIrxiQ3hHnQYX7GdmHB2EjaFTBnw7BjfdLvfbk+wHXaUQNM0J5NB9tXHTeIoZoAaFthlRB82w\/bnYyPyZs7pGGc2PD2dgyiyqDjG0X0vFarOm59jQmUeKfA5xMr21TR38yKdGoUUzqntha+bdqq2\/sFz0SNRnz0hxlJeRcFW5eNgY9U57jovObhLd0TrCYUqOlIiC79fKlyBabknv8cZFjRd0F6VNvpwL7YfmalpzFH65Eul1ImmNhYMfn25e5+w6Lw+K4oxPH+1dPe1kCoWPQ37m8aDpdUj6m\/A8HX+uhGSAMoDUHM5IKrG\/Lm5cPiJ\/aN0bd\/qQYdO0bY7Yt80UwOrTYfJ2Rkb\/3rYkxCdDHP06jllloFAItTIkLhU56dRReJR7klXu7MdL8kybiXcKkGVPb1CbINBZYw\/+HZn7qHxIsCoS5NlbJr8JSi5E975UesWpPQ4TQEUCIuOJaXtG+CYMTvF7Sj51JVyaJTz1V+RR1jfH+Kty4K8125rc47hldgTWTKmeORx4eFFnmjeontR8NGdMreE4vQKapKGgmGNHfbh52BUEVfzMtnM2kULfu73BKnBe5u0J3N6G7iOAJcjfoADIFHRcTfs0NtS2S0MGQTRroqgx5MOG\/Zb5b724WghyHDKPizH\/UfFJHYNS8iDONNcUtAYYzSfGuHu2G5YA8aAIL52bn\/B6rNAGvKpPvMKIjHDqNDOtfDw0zZW+TcogKlRfAEbx6A0NSUUBqBB3EKCbiJPxG6vblEV41WAuhyrvfj4D1VSivkKOBRUHkl85KBA2MhH6bpb4eKt8TSQ62p5i72OB7hqEMWthNl2Vvmwhj7OmnGjVrL1uR2ow\/z6y8nluDxLRGc63yghr1C6zUL4iEeiAjnx50zA7sNZFPtjY4YBi2s8pKIoO08GfJGZgQMNaLLThxH9DdQQS5e\/6x83L1Ifhq5wUtusmHytt8WqFcUH2WHt00i2g159INdA2RO20CnTS3SzogQgS\/g\/hDy92Wrhc0wl4IRclUZfx4PTMGy3hSPOApH4859Nz8Xxldig1+wKgr\/w\/2REmPfz4sNXhDLEadGnSBpO5mVkCUEMKN8VO3biF9CkJ1oCt0+eqRjgd67kxyzDrbR+JgWSvSRa6z1CB3AZRp4t6ANYwhIsxKQP4zAcOOeUgutPq0l\/Gn+SXQmD0IUodAyCSHcg4BdEfrzUMtgLlqh2GWp+\/CvqZgGglsUfDN9\/2Lz+gUtZ4OwhbkWHk\/luQqxOOfGH1g5WPhNiteNI8RCtTmxGL2TQGV4I+V8d8uL8JZuuVDlIpaSxDg\/v7BxekG0lBu0yUemkmblT+XJn16UzLE0Kk6JGLt+IG+5wkFEjc5JLiH4VUqcrsENT925GGwjTpiuOVSDgE5Njda8VI33qsVU+9jAa3oIUwk7zYZFFzHcBqx4Gd5KGtuCzLvB3nw323YuxwZmZWt9cYVKKK8jR39WGhGpXGMJGSGBLKqYV3O1PdLHnU3DwaQsm9XG9jqjfC2fGm+AurSEEcGKCo","iv":"69cff9d0096696a8bbf5c680e85aa283","s":"34db03941621fb07"}

Chanel is contesting. Image credit: What Goes Around Comes Around

Chanel is contesting. Image credit: What Goes Around Comes Around

What Goes Around Comes Around Web site with Chanel vintage merchandise. Image credit: What Goes Around Comes Around

What Goes Around Comes Around Web site with Chanel vintage merchandise. Image credit: What Goes Around Comes Around There it is again: Chanel bag shown in What Goes Around Comes Around Instagram post. Image credit: What Goes Around Comes Around Instagram

There it is again: Chanel bag shown in What Goes Around Comes Around Instagram post. Image credit: What Goes Around Comes Around Instagram That's right, Chanel again: What Goes Around Comes Around Facebook post. Image credit: What Goes Around Comes Around Facebook

That's right, Chanel again: What Goes Around Comes Around Facebook post. Image credit: What Goes Around Comes Around Facebook More in the letter than the spirit: What Goes Around Comes Around "Letter of Authenticity" for Chanel vintage product. Image credit: What Goes Around Comes Around

More in the letter than the spirit: What Goes Around Comes Around "Letter of Authenticity" for Chanel vintage product. Image credit: What Goes Around Comes Around Milton Springut is a partner at Springut Law PC

Milton Springut is a partner at Springut Law PC

What the heck is “weak sauce”?

Sarcastically submitted