- About

- Subscribe Now

- New York,

April 26, 2019

Milton Springut is a partner at Springut Law PC

Milton Springut is a partner at Springut Law PC

Design patents can be a useful tool for luxury goods and fashion designers to protect their creative designs, but only if the requirements and limitations are understood.

A recent lawsuit between shoe designer Eliya and manufacturer Skechers over Skechers’ design patent provides a good opportunity for understanding these issues.

Rather than opining on who is right, we walk you through the facts and law of the dispute, and let you be the judge.

Background

Skechers sent a letter to Eliya, charging that Eliya’s “Bow Shoe” infringed its design patent. Eliya then sued in federal court for a declaration that its shoes do not infringe the patent and, in any case, the patent is invalid.

Eliya argued, among other things, that the same design was marketed by Puma two years before Skechers even applied for the patent.

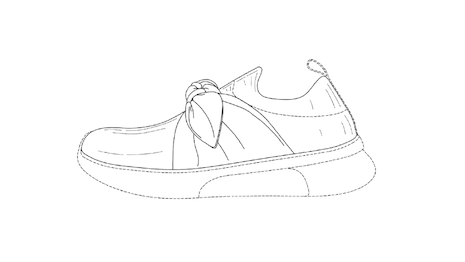

Here are the key pictures:

Skechers design patent

Skechers design patent

Eliya Bow shoe

Eliya Bow shoe

Puma Bow shoe

Puma Bow shoe

Design patents

Design patents protect the ornamental design of a product – the product’s shape and surface decoration, not how the product functions.

When someone creates a new design, they have to apply to the Patent Office to obtain a design patent. Design patents now last 15 years from the time they are granted and give the holder the right to prevent others from manufacturing or selling any product with the design.

A design patent is directed to and claims one design. The patent includes sketches or photographs showing the product from all angles.

The Skechers patent has seven sketches showing the shoe design from different angles. While in this article we only include one, you can view all of the patent sketches by clicking here.

Is there infringement?

The test for design patent infringement is known as the ordinary observer test. That is, would an ordinary purchaser perceive the designs as substantially the same, so that he or she might purchase the one believing it is the other?

Here, the question would be, would purchasers believe Eliya’s design is Skechers’?

In its complaint, Eliya alleged that its shoe design “does not embody the overall effects of” Skechers’ patent. This argument is a bit misleading. A design patent does not have to cover the entirety of a product – only part of a design can be claimed. Unclaimed parts are shown in dotted lines – as Skechers’ patent in fact does. So Skechers’ patent protects only the shoe upper – the part shown in solid lines, including the bow. So, the question is, will purchasers think that that part of Eliya’s shoe is the same as Skechers’?

How does prior art affect infringement?

But the Eliya case is a bit more complicated.

Where only the patented design and the accused product are compared, they often will look the same. But often, as in the Eliya dispute, third party “prior art” is also involved. “Prior art” is a legal term which simply means all the designs already known to the public before the patent was applied for.

Eliya notes the Puma shoe that was on the market two years before Skechers even applied for a patent, so it is “prior art.”

In that situation, the ordinary observer is imagined to know and be aware of the prior art, and discount similarities to it. Only the remaining elements in the patent count, and then those remaining elements have to be compared to the elements in the accused item.

So, in the Eliya case, the test would have to include someone who knows about the Puma shoe design, focuses on the differences between the Skechers and Puma shoe, and still believes that the Eliya shoe embodies the Skechers’ patented design.

On the other hand, if the differences between the Skechers shoe and the Puma shoe are minor, then that might make it less likely that the Eliya shoe would be thought of as Skechers’.

So, you judge: would a purchaser who knows about both the Puma and Skechers designs believe that Eliya was like Skechers?

Invalidity: Prior art

Eliya also challenged the validity of Skechers’ patent.

For a patent to be valid, the design has to be “novel,” meaning that it is new as compared other designs previously known to the public. A company such as Eliya accused of infringement can cite prior art – the Puma shoe, for example – and argue that the patent is not valid, because the prior art shows it is not new. This is called “anticipation” – the prior art anticipates the patent. The prior art need not be well-known or popular – so long as it was publicly available before the patent application, it qualifies.

The general rule is that which infringes if it comes after anticipates if it comes before. So, the same infringement test applies in reverse. If the Puma shoe is close enough to Skechers’ patent to cause the ordinary purchaser to believe they are the same, then it would anticipate – and hence invalidate – Skechers’ patent.

Again, look at the pictures and come to your own conclusion.

Invalidity: Functionality

Eliya raised another validity challenge.

Design patents protect only the ornamental appearance of a product. Purely “functional” designs – designs whose sole purpose is to make the product work − do not qualify for design patent protection. But the fact that the product performs a useful function does not answer the question of functionality.

Rather, to invalidate a design patent as functional it has to be shown that the overall appearance of the design is “dictated by function.” In other words, for the object to work, it has to look that way.

Most design patents will include functional aspects, but that by itself will not invalidate the patent. The patent is still valid but is limited to the ornamental – meaning, non-functional – portions.

Eliya has alleged, without explaining why, that the bow feature of Skechers’ patented design is functional. Perhaps, the bow allows the user to loosen and tighten the shoe. That could be a functionality argument.

But, Skechers’ patent does not protect against any shoe with a bow – that would indeed be invalid. It protects against a shoe with a bow that looks like the shoe sketched in the patent. The question is, does the design have to look that way to achieve the functionality of loosening and tightening the shoe? Or would another, differently appearing bow design work just as well to loosen and tighten the shoe?

Again, you be the judge.

DESIGN PATENTS can be powerful tools to protect new fashion designs. But, as with all patents, they are limited by what was known before.

Understanding how design patents operate can help designers and luxury goods and fashion companies decide the best way to protect their designs. The Eliya-Skechers dispute provides a good, basic illustration of these principles.

Milton Springut is a partner at Springut Law PC, New York. Reach him at ms@springutlaw.com. Mr. Springut's opinions are solely his.

Share your thoughts. Click here