By Milton Springut

A recent lawsuit, filed in Texas and then transferred to New York, pits luxury fashion designer Sophie Theallet against Swedish discount retailer H&M.

The suit illustrates how the new world of social media and social influencers has affected both the marketing of luxury and fashion goods and enforcement of designers’ rights.

Ms. Theallet’s complaint tells a common story: a low-cost copyist rips off a designer’s creativity. But it also reflects a new reality: the heavy use of social media and influencers, both by fashion designers and design copyists.

This new reality impacts both Ms. Theallet’s legal claims and enforcement of her rights.

Theallet promotes new collection through social media

Ms. Theallet is a fashion designer, made famous when her creations were worn by, among others, then-First Lady Michelle Obama.

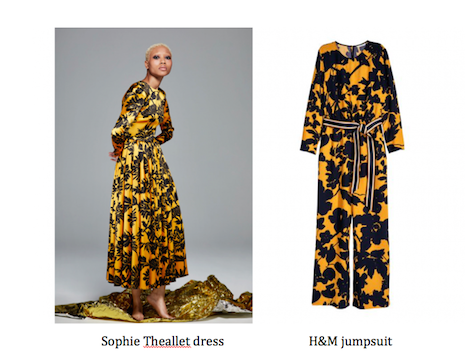

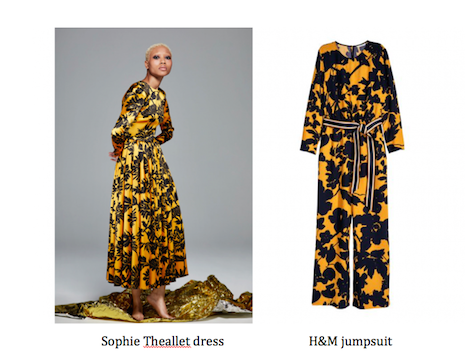

In 2016, she created a yellow-and-black floral print design for a fabric (see lead photo above).

Ms. Theallet registered the fabric design in the U.S. Copyright Office and created a collection incorporating that design (dubbed the ST Collection), which, she alleges, “embodies a comfortable look and feel – e.g., flowing dresses and a loungey jumpsuit.”

When combined with the fabric pattern, that gives her ST Collection a distinctive look, protected (she claims) as “trade dress.”

Even before the new ST Collection went to market, Ms. Theallet and her company were busy promoting it.

As her complaint alleges, “[f]or emerging designers, such as Ms. Theallet, it is understood in the fashion industry that dressing celebrities and social media ‘influencers’ is the most effective form of marketing available. Instagram is widely recognized as the leading platform for ‘influencer marketing.’”

So, Ms. Theallet provided garments from the new ST Collection to celebrities to be worn at various events.

Prominent among these was Kendall Jenner, “the most followed model on Instagram.”

In 2017, Ms. Jenner posted pictures of herself and other models wearing Ms. Theallet’s items, which garnered over 2.5 million “likes” and nearly 200,000 comments.

Another photo of Ms. Jenner wearing Ms. Theallet’s jumpsuit was posted on Snapchat. The photo went “viral” and was featured on several fashion blogs. Several other celebrities wore her garments at events or television appearances, and then posted photos on their Instagram accounts.

This marketing strategy, Ms. Theallet alleges, is crucial to driving consumer demand:

The association of a clothing brand with a celebrity whom millions of consumers “follow” drives the sale of consumer-ready clothes, which in turn fuels the profitability of fashion retailers. This is the model that Plaintiffs employed by dressing Ms. Jenner and other celebrities in the distinctive ST Collection garments for high profile events, eliciting millions of views and responses. The social media attention and other forms of publicity that surround celebrity fashion choices drew attention to Plaintiffs’ brand and anticipation for the upcoming consumer line.

So Ms. Theallet’s pre-release marketing efforts seemed to be succeeding – millions were exposed to her new design and collection.

But, someone else was also watching – discount retailer H&M.

H&M, in fact, already had a relationship with Ms. Jenner on other projects, and “followed” her Instagram account.

Sophie Theallet dress compared to the H&M jumpsuit. Image credits: Sophie Theallet, H&M

Sophie Theallet dress compared to the H&M jumpsuit. Image credits: Sophie Theallet, H&M

Theallet discovers H&M is copying and brings suit

Ms. Theallet discovered the problem with H&M on social media.

In 2018, a Turkish Instagram poster named Marka Klonlari posted a photo of a model wearing Ms. Theallet’s jumpsuit next to one of H&M’s jumpsuits. Klonlari’s Instagram page, https://www.instagram.com/markaklonlari/, is dedicated to posts showing inexpensive copies of high-fashion designs.

Ms. Klonlari’s post included the tag #sophietheallet, and that came to the attention of someone at Ms. Theallet’s company. Ms. Theallet then posted the comparison on her own Instagram account, and scolded H&M for its “blatant copying of her designs.”

Rather than stop selling its [allegedly] copied collection, H&M used its own social media strategy. It promoted the copied items on its own account, and several media bloggers and Instagram posters followed suit.

This misappropriation of Ms. Theallet’s designs apparently caused her marketing strategy to falter. H&M, in effect, not only misappropriated Ms. Theallet’s designs, but it captured the market perception of the new design as Ms. Theallet’s.

So Ms. Theallet filed suit alleging copyright and trade dress infringement, as well as unfair competition.

How social media marketing impacts Theallet's legal claims

While the core of Ms. Theallet’s complaint presents a garden variety story of design piracy, the heavy use of social media by both sides impacts the claims.

Copyright claim

Ms. Theallet’s strongest claim appears to be copyright infringement. Her registered fabric design indeed seems to have been closely copied by H&M.

Social media promotion makes one difference here.

To show copyright infringement, generally one must show that the defendant copied the design. Unlike a patent, independent creation is not an infringement.

Since direct evidence of copying rarely can be found, over the years courts have developed a two-step way of evidencing copying: access and substantial similarity.

If the defendant had access to the design, and the defendant’s design is very similar, then copying will be presumed.

Once a design is publicly released, then access is easy to prove – anyone can purchase an item and copy it.

The Theallet case illustrates how access can be shown even prior to release.

Ms. Theallet’s marketing strategy called for significant publicity through social media and celebrity wearing of her designs well before release of her collection to the public. The Instagram account of her chosen influencer, Kendall Jenner, was followed by the defendant, H&M.

H&M and the whole fashion industry thus clearly had access to Ms. Theallet’s designs well before she released them to the public. This is one way that social media impacts enforcement: as soon as a design is promoted, copyists have access, and can copy the design.

While this fact eases Ms. Theallet’s legal burden of proof, it also accelerates the time in which fashion designers may be victims of copying.

Trade dress claim

Ms. Theallet’s trade dress claim seems much weaker.

For one thing, what Ms. Theallet’s trade dress exactly is, is poorly defined. Courts require a claimed “trade dress” to be well defined before they will enforce it.

Second, such a claim requires a showing that the public associates the design with a single designer, not merely viewing it as aesthetically pleasing.

Although her complaint points to some media comments that support this contention, it is undercut by the fact that H&M entered the market before her, and, as she claims, undermined her marketing efforts.

This timeline – H&M’s infringement commenced before Ms. Theallet ever released her collection for sale – means that it is much harder for Ms. Theallet to prove that her designs are strongly associated only with her.

But one aspect that may support her claim is H&M’s own marketing efforts.

Ms. Theallet’s complaint alleges that H&M has in the recent past partnered with other designers – Balmain and Giambattista Valli – to market ready-to-wear versions of their high-end designs. This has included use of the same influencer, Ms. Jenner, and extensive Instagram promotion.

Ms. Theallet alleges that these marketing campaigns bore a “striking” similarity to what H&M did to promote its knockoff line, with one big difference: her design was pirated, while the other designers’ were licensed.

The average consumer would likely be mislead into believing that H&M and Ms. Theallet had a similar arrangement.

That is what the law calls “confusion as to sponsorship,” which means that the consumer is misled to believe that the defendant’s products are sponsored or licensed by the plaintiff.

The use of a very similar marketing arrangement by H&M, and its prior history of partnering with other designs, makes it more likely that consumer will believe that H&M and Ms. Theallet have entered into a similar arrangement, especially given the close similarity of the designs.

Takeaways

So what lessons can designers, luxury goods makers and fashion houses learn?

- Secure foundation of rights early. As we have written before, the default rule in American law is that anything not protected by some legal right is free for copying. That means that the designer has to secure these rights. In the age of social media where new designs, even before release, are viewed by millions, early foundation work is crucial.

- Monitor social media. Monitoring social media for possible knockoffs is a quick way to be alerted early on as to possible issues. Searches for the brand name (#BrandX) may reveal important intelligence about how the market is viewing the brand.

- Monitor so-called copycat sites. Sites devoted to shaming knockoffs can reveal valuable intelligence about infringers.

THE SOPHIE THEALLET case is a good case study for how social media and influencers have come to dominate promotion of fashion items. It also illustrates how this new marketing reality affects enforcement of legal rights in the fashion industry, and the lessons that designers need to learn to enhance their ability to enforce these rights.

Milton Springut is a partner at Springut Law PC

Milton Springut is a partner at Springut Law PC

Milton Springut is a partner at Springut Law PC, New York. Reach him at [email protected]. Mr. Springut's opinions are solely his.

{"ct":"waj87PRQ9M9K2yQaJXGrZmh4\/4z03\/BYBBgvpcYAieqtO6ODXNN3VGJJiOO+1baNm5LXfqHkFe1poHKs9+AFy1lc9O\/Y7fpm8A79gbKjkVorXYPdsLldW7johk0IEtPqrkL1IAGb0Aig2GPUK6RghjRxIBBjcwiDr5fcIsl\/oUbFbtXHctuhSR8cRU8Rzhy\/BhPYAZdV\/KzpYdDlGdSjXF\/WXZPfe15snLPBqQYMq22iEe0u4I3ICECbWiH7LNXeq0OHVph4HWWwg2fw0sOsVO03CIiau16EyQYhHK7ixcOqb\/5jScvUEXbDIY5XwUC\/x6YE72s6n2wOm+equVQp4PlkdJOwmMp4+7XujyTdWldeyn7EjznI2MU45lts2Rguda6zX8ev0\/9P5rtGDfZYki5oI2enTAkHnmZmzQ34O9IlJienBlCVGFAPFR4yBw2eyZxSLFAegrWM9slfdUKHTTd6FVwFhu6evu1hQp0PjRwRL0UaiOFIhsuNo53EIcEprZii5S3goRIg86kRyXkKpBHr+CL5+EvGZS55\/ZPxWxRtR45pxQJ2HReOyyj9McMK9LeUWT7XMQUmaMgjWgorX5PWZZZk00O8mcCV+88FrQKlvnZ5W32L0eGRl\/P5bleMh3XgogBB5cQVf+M1I7OsKrCj+DCUdd5o3AoNU34y4csLlKUuzro0zusG4UUyZSHeS5VcQFCS\/PzXak\/IDHguJ7Z4LeCKZUVhQntbpcmQ9Y2bojf\/PsIC7fHty1A2oj3bJvp88H9PbWsQQ13djpDo8jz\/uuQQbkCQAMOstje80YCat\/Dakryo\/RbGY9fj53ZkXW3yUel7LETrFerEhjLuwHBGuHd38SAz2+sRpH5JU0RGc+QOXO+rGHZkofonhNGlqlIvCRmq2Mbm2wDvwiNB\/lcp7SCb8qR89U79SGEUPR3H1dICwJWQMaZeeLbVnbRSLPj9RYB4TJpRd42iGCMOOojy0ceuj1S5DiCniKucVzr9SULfBuR6ZkTZCAeZnYYaAFQF\/dxhXXDORwP5q9gOvvxh8sZ\/751hhn3NBKWdhBoEu8MvWVyVjbF2v6REmM4XkhSVW\/ZKw9SqDPwogS6fG4f1c8GuSDjtjhjfUlQnX\/5vVu1ryngdLL3zb4xAqbmBrEURjd3hxfu+pP2jw5a1tanmzMlFUL0iuNPttRO7sV+WOPpyYbYXk0vFjBMNeolD1NhTSmyTz5GtkNS6Ra+\/LHzBjfLY\/NQtVSlBVV1N9wvVn3EJg5alHHZ4HjK+jJHlnEl5CzREa\/BIEoDx5nGTtbHSf8Ir+4PGmnEQCyKhK3fPNQISRO80HoDopnUpILiLiAx9jVrh+dc9QYFgY6weBF8RgdSJfMiJCOfR+P3IXgoiVKhYl42IuH8O\/3xept0G1xpZ8SNh1noRkTEU0QhOWLKb7o655bt1fFvk8fxvua2css89Xj6ggoJgFNJ5iQfnZbmnk5A6CVeQ29Gush4Jj4U7VThW6Bf+PpLvrCvTWeUmSZ62AJIiDON7YwbfW52T4N\/A6jnsF8jMLdnOiYpekqjl6ouu0Y93KcTLC3nh0mvfKq7TWnkl6OU5MlxvGDQbHIBPM0pKucsl0QMs2UKTWI0NYOvREUL0VcploRdeV8rWEdyYFSOO4r8pYUh8PeJmcv4CaPFunjOLt1hxooS9Yz\/Jjv7Dzq1roX9R1qk7rRrHson2ID0dU3jkmnGDSImG2OYGqgNzeEhndblanrlTgAbA5u2Opv9CblaPQsK1x3SpbR89jfMeB2uLarjVEIm3sUZdWxn5ky3EAGZ\/i6VSDa2B+oFTK1sl0qOZNY2gra73aLPlqGEmxTb0b9liFxCeJsB1lt1x28ihdVF86vnwGWPV6AobdRdS9qKW9vAvQqE9M+j8+ieKSz51qeL7VBJxuPi6\/lUnYi+ZACR90hGxKHLl4X07wIMYbhxrDe76sH4USMfxSQkh6q3JVqGP5iVuFpCyY\/7n0eo2mG1tlGnlQjPsiQd\/RLh1Eg5DTL0MN5eOBrqmeHMcym14EtqVS9hgWeQwVkZNhe0o11Eqcc7WHWybL7JcirV48+di8BNRQj8tQDjV9isuCnuME3S92NBSt3IMJhRT+iF2h\/49EJliuizbGr0QHiFKUKse0ucpK7+cjOYiVVdlmAKyFxxOM4XHShyCwcjtMAHY2NmbihSopEnoLQjW0TC7JgK9Gy6gefy9n5mzz5x55X\/zeyDXyCg88cGpfc6YGpJaCecilj8V3\/86R053kPFhWb90\/xBDH4UyjMlyR\/64s3\/X9oPYSuq7PTTzX9x2Qg1klbi+lk4O3JMyWWYYdFhMc6q51xtHRA7FLm\/uWDS3CwQiAXvsYkVx3aCXUmEdHWv9i46tHwKj2SiY1vQmSBsUiaJg1APrTQTBxOXcIPrq3ZuCVDzVYwNu8Z4nybEzCHjoURXdC+clQIfduZIhchsC4JN0u7oe\/RKG94ZhaXHRTAwWMyO46yCyml6sOw5cSlDMS+eYten1\/ny98W2QjWJUuFVkXzmXvzHzij8o1b+w6xI4THEIq\/cjyCWoNl\/3EyP6L8uINPwHcA4AaZi8GB\/Zm9W9lgrbyfYBWIQNrAw54oV3o5aqx0kAMMZY\/x8PbcPwfNKYFQSU9HZUB\/adLQDeidJxdhj07\/1JdMqYHmFujh\/Km3DJUkYY11xM7SsrbC6TqJNxHPQnOk6WB3YE9LjfJJf9yhpbG1bbJsoxiOQ1ZQk5uo4TeIQwYDO7+L6Fg6coMYgWXPf7RxJ0BxNKhc8I6Zg+1vn9zPI+cA2KBrMrPQjNlpBCqlGvE41juD9RPDPyEQlVvan0m3DrUsDPbrSFO7RsKfEoabLi5XWV3\/024yoweyqOTqAZwb5AGQKZbMIlYebO6OkNvpfzvpgGIM+xU\/mOJzRePsK3lldi2Pzm3d2w4WfiRlNXVjkMEQIKqTYS5Ig2K+lmbDtxc4QhkU1RoPIctBHpTRIZy9atSUYrW3Gn1Bd9vc5AI2JZoR+pMg0p6ttmLscdHVCVMybKwUSCl0Wwntlscp7huZJ+NB23blsRj8OwP9PRs0FiQlnW2LjEHKNEagr\/QdrXH93Jq\/CNTzf1nVnfbUxlkpoT6J9VP5pasarLtaKu+GdQCVQsr3H6aGy+UoUc9E6B2uEcn1oiZZPvhcybd\/zIHcYheMq8NP0D24oN5p1\/\/RigMYdK9IjAO+8DtkVLGzV3XwuaC3CK\/9Y+9VyTpDHuPKvWB+VRePQCbEwlkeuSOmZWEL65XeXPbHpzgCcHJXL0UprSbxHTjMffulZSm+yh1nl4MaaF6tuZ5g\/S0X\/GXAIWWUKvaP7v3OjrATVtV4fjOqvUCKuUaJzQSyMH55nHRGa9y\/SxasEQPlxuzDq4Yjd9YBxcZOXrpdobMV2e4YYxf\/B9eI6MWGbyouknzrU1S0aN8ARP1YsuI\/DjVegBuClfU0+JY8WR4YB87\/gNZv\/ES2W3p4Ed4mqFWfV5HYc4vrVW+5p2ScyY1GCj8BImORMCNdbd9tWBHYbITWpHF171YPE5nsvHemqj3\/gibDKFb2S02irP4y25LixbzIw3j0cqlrD+bxqz1zEt6aLHOIpO9ijFJMVBFXcHs4DWI2X89K3LUdx5YBQ2fY9w1b68MUoKPgWWwZWkKRyRim2TJRptXvYRYENO6rVLh8AWEi\/QAOVrFX+JE\/tYWcPbo\/fOQ4tqAkExbrC+M4fyUa6f8\/xrCJuL0oAUlwZY2gTOaCprKJDrYovxw1JT42Nkl8vl\/tgeyMzRx5GnRx0p50Ih4HiUEoXFSCWjw9VF3\/xsGeidGmc7+vxdVWwkcylc6K9Gz\/pUuNgTUElz2uVlLewptdpC3Ju3725hN+ufY075aT\/7idzbFDZ5+le3lz2As0JduNy+2rO1CuNPBa0RJUir3ss8vXEHPzZ850Rg+NMYCZHEHuHS0GaXjFPhgyrpdVmYCMRKV5J+GYNgamfGvXIQtO1y+1cVuzEyirFODXXfJsj3E9EBode19z6HCPhzyUaIfHbQ6+JHzICEl6LEbD8sHH9JdQQGInUw0Mzqiz7kx1OoWFMemRsN5IgEKSy3yFVWqkk0CJ5h1jmbavOvYw4apLg\/+qG4EojjMOLfks18mdaaUBPlejupiaOf5lXGrLAaeVmR4Eu2l7GqCR0aIbQp+MhtiC9Q32Zi6iFnWqIUEy4xX0f47m6jDngLsR2ViOkotvT5Im\/RAlBsBmAORO+I4FIs6sLOQ80aPW5jiHNSq8VMvBEpaV7TTZt8IAqIHX6ybJpQhqFNrX\/SmTsqAmBVsjCpdgszhijFMNQjRtuXdFR+GQj01Ryd+Ybs\/RJu6gP53GTJ9UC44km6BX4GpFGJv5JmtOje1ySk\/y88EjzilvSRRn4u13gmYgDFpMRL4Bm6jGdmnZJ8SG\/PXcLzyxL5rf67f97NvGhQBeKiu3++gb5K2rS5E92c1ismOg7j5uaJqFq\/8IfVdTttUZi6rGQYtpcIr1\/nx0WE8DdRMfxssbDCrPwX0FLlU7UZz\/Oph4BYVAUEFLs6bLOQ0vw8xe+Sx7HsRibMNnjmzmHsigNICBTmZa2KVs4NwbCoWtq6CchuaDhY1x20C4U9NeHFdv3FyJ73xyXzycyeBzTfhuQxldQayjHZ9NCSaOsRAM9GqE1KGx+nC3X1Jk4F9282bWayird41rUsDkkATk6axsXjie3LXopZ0RBM9nU5qeHpVlFaY7FV\/z2+H6RjC1AqrJqXdblWrBANqx03Jsy64SONsLf5nccyDYjNn6ONn+ugbDzZwL1D+TERWn3XXtvLhjN10Di2TI\/5T4NQqAUW9aWXewlWpkLDlaZkhWrF1C+bTPJ2H55EKMvTereSjG0Y+VxcPA69b\/ogqA+rCWXoEfTHTZqISL4zza3hEcM+V9OogGkehWwue8uoahmQ9Le6Nq5nB+Dr4C5igJ5EM6Zz9nFtJwsMVi8zWpWn0V7THc3AvpLw6YF1NuguIhq15ta0oMgTYIeMNZO\/cD6uO2fybU18XaD4RD8aD2U9na2I17tmUiRqH7x6TbU72sIOHtxmuckuFG\/mylAuVDw40R2c+OnCd\/Y1NVDMMI2Wah2uxHWTeiXDdbRkvYSp0VAs3YwbRVvYJh\/QGQGe6sYrVShwBH9T7b9Wnn9tAHvmEyhC6AmV1003ZsLK88BqxwhuZ71CasMCjrSXlKLuhVYqgo\/pvX4vM4wgl7Kynvnkx5Ov39ML\/Z3jRDYy35w+DHo0fe5RapapKeBWh4rBd0I199LaNP6c3DooD\/PriCwuVKnMTLNc3SAgRbpVau5KEkAwnlM+5QwlFureo\/GBw2sIrYDClOErrrNvF\/SVCp+iUz2muco09RDCvIztfGO3Ai\/\/iMpJKHYJuKSKhH7jiWeRmq0i4YsLyLiaF\/\/cZhxOddLMpF78rwIrWHu\/w8W\/t0Oa+SJCyySjEFmp4dZpPBjzWT4dOgQistaCkhef6j9ZTuNb\/DUiTqwzNRhA+nGnJeUiKHuCZA+eIPMxD\/hNI6zjILRbcpmzDjPE8z9nj9tkqIGglXAS4OBPoz2NdsdgKRV40xf+ws6k0iano8pmy2PVxGElAg3yNtu9RrmnC9FKQgAHCsHFL1atZwFrpTUyHMq3352FaXXzeRGJXSSTJe3ewnhoJ3fpulc4EDcwfinvlROLkuJHsFfIZVDfeeQOFB39IqDTUMvexShbdq4CleD5TkTbveJQ2ED+LlZ6rPZfjvu\/LlkkjnIb7T7t2uhY8z\/f\/INaeq3FKZJScu+DDmbYQUX9n6uFBt5RjXeAWr3c5J6ICVWMoQ28PpWCmRPqrcBPJfV8bdnsub95uNCwMOou0mYFBr6YKhaJUbc9bqXCvpnw3EnvakfJWwR6V+\/zD3GZER5u77T1ph3sx7l7YO7wtd\/iBnljXi9RuO2aiAgLi85c3+C1ZkYnTWkSuDZwwCTyoAlcaYXBHqqLdoxzJePq4TZbsSdNG9drLGKQE+BXwBuN0c4G+5madN0FyURlLPv4QIWBkSNnj4LpWVxm7N+fxUPqOWpdOkpfp30dVqbB2h1ueHIOvo37\/k0XRlNSFre7oqQl5T0IUyaZRVJ492tq6bQfFBltar3+CnFDsS6gFT13PIypy3uSgkTKlevO7n0\/QjUZOH+cmQFa4TCtUk\/xtYvKXo+4ym7+6\/Ne5VoYnbLGma8v0ki\/6ceS2sW3l4hyHYZF9SyU8VMl0p8WFRlQ\/OQdxhrwf3kK0j4BxKNKOlAhIufizFM5M3Oqcv8ev0uEaSzP8pLa10Xskj\/SuEkHZnAod00JsBa9bSZgumcW1BtZXJLdPVeiqTjrneuz7QieFGyl1MO7lmqnAUyYwerT914qooCSKDd7n2u7jVduio9FfGXX2XXl15cu3PloWneGkrQ+bNlPLRE+r5NdbmKO2EMwZY5jsGmE8holluFzWuIvcvVSuiuQBZfRGmdL\/rOYUmJn\/qqQEPZGo84cgcpd2dJh83PiGWisOCyqqrOOmlGhLX5N3C8PzrnqPH7+LKnZ0iNWj+JMOTWLUZF5tGoHeG11p+LOzsn+5EL1Q+rZnBDu7cS6lvSok\/YFwFJlN5a4DIWLjJsOLzJHcqutghfMlt8\/v+vH7SF9ys1YV\/ONFKXcsWqNUZvcUgUpqI6MNWAPCM59vZFTqlNbqdXuOIhU8\/x3V3pFPyAgCIaq8AspgEpPWkE1fCRs0KVWvWzmab5yUyU846+qcIEyAdDyVBhXN7pc93RxXjqy5Ml\/fWpYv1WQIkodC0I76qV08eHPb1rIjirNRmVc7K7P+Jqk7PZOhIMn8nBCwLqC4RkNAvH0TG+wUU7nSwGUdwRjnjx5iythYztaoNBu7NSe8yZRReQfM3WDiTeBfbzmVlGmADQfXavVSdUwRCfGCljrIxKwIo349WBm9QStB\/W5TiMUFCB0wy8xAiqXlHiQWgeaIhZPmBPaZsUl7NlQliuqGvDDuXObCIDIHpi94YY0wS2zNIP3BcekF+NcI4ZkqDoVTsmn12hby5vTH5ClZRfn4DyaE\/FtIVH5W6lBRouua90CnIhuw3fj+THJV7Q+KraMW0O9RJSZnRA9+PWlUVCOfAnEJmH9K\/5Eb83syIOn6aTN1TeWavmdLYsoZoJi3IHc69LchzA8T9ZszuU5p0gaKoajIiA7ufMWiYW81g4BYjCrDD1WslsEkoRmtqFE4YBzcjmMAJzoicu5plrRnMuV7OYcQknCZhny9QJBciEHSUdYmTha7FABkh3Mityp1WxOpfGlHx9X0qoHZzWXI0sTBXwK23I1x6B2rojBFqpakYYv8CQ0Hcs4t7NrI6kbq3n8IPDJCgWQaQluCawpgItO95eui0P3gx50oQ7OggIJhhVwOiXsQ4ALwIT45C188r3J3D9ZEfHrM0xeQJK8vMQqKBNQ0oA6s64UqtC81D4ykkaREAqXWuV03yjnr2YCwrW+xt0hbtb5e2ZWXOTrnZpWLhOwAZrSs4oLdaSc8CNwD1qxMr+QtzjxDfmbbWHGcK2fd3uIVgSpzoGuBRvOBDCDo1iXAqGWmkjLEoGnnVAGShVC9eIY0mSNkVOJ5cp1r+GjodW8+Tm1MbVNHxHQdmiXckHwLoW8vADB62mjxldSscf92VnM29iQPmSpyOinXsCinlnmci8XU2ez09Ez\/BQofJzC8vaGhrd9rjeI7q33nR+ydXl\/60YocqkLEkVB1QgdjZYDdUMmJVruq564LJKcuxy3wjfFqVqQFZmOsdNnntMws1NpiTRBSCC0EBrmJu6j70CRVEuLVZCLe7jpxHbQ6TpeL6axIY9JNblPOESOYVEbkM3R44XJB5PgPysWBg06zH8DOiYBVDDBpYabFNBtBtvGmhUfxkL+h2wvEJcjtXiQtfL5LTkvV9aq1REil7mXe5MOiRPhzkoOOoGgkJlvYTdyIFPkE+Ht+g4EsYGHjHfvJuEvXJyp+aQHffVF9OAqQ0pUHkZrEJCUyBCAln3POTazOJcfFvoejQSJk8GD8XMSJdt+gyd0ZYqPrYfIeb5dAurePk\/Gxqs2HieqKeJuA1o5TnHsxcW0WyasEpISAgzfV5Y0reZlR7s9Tk4I3ng2YcU43fkRJA34s7DRqNoO2ksLeNUXukBBtLkGSzr7g8Vd\/wY0m1SfU5bkNZoxxKhbCFM06YkCP56EtOAWomr8r0U1SGb+aTGHrOEmp9kJ9LxTy\/DOwjuWXqIgFPZQ2Bco901YW5kgaE51xbTnwByy4mbCAVABLbIVkIAcOLZU3gQNrhj3kWwNsfLDV9qxaauJ3ugx+bzXMmKZsb1aZhGdyGqXXOrX7slQ4Ej\/RU2BVZPY3FG1deNtpxa0OvH4mNCWb5qTOZohY6z8hjeDPsDQSpqSSvkLTH2\/8xmmzomxqMV4CnqrHtU5gys3b7o38SR\/rixLpZl349K8f93y5ybsACTgHMGMqaKVJoe5onZ+ol9Gj4RfOzEVubbv+cw0UmVErjdVivIzu\/2ZBBvWxArHSwRqK45+xlK7\/vhtAFfuOfHcqpTAGiZXZbjyr\/f\/iz1CFc88Qj2X9kQ7peot\/vSJoFzTKC4DocY\/+uNXJyRnZp49xIwkgKR00FDAjFQ56xQhoeKJvbdv+SbqrUi5Xh29+V8SXFGrRetCMo5QRuTnCvXUr9UjLOCtHHntEKuXHbpP0VLkHhutyL7Otg6zN1p\/bCl1G77MwsEXv5B5BkQgN6T2tVRKkar34+MO8elnpEAjY4LKK2xfOFcOEnJD70PfwBjAZbbddX\/5ITrFwUOF4hgEyJRUlrur4zmfzrB2sFk2JwLao5WCh6mQXYV7XcquZ9z1jOh6U5FcbJaPN\/J\/evh3PRYuhhzp254avV0BSCwB0i7vC1oWjWegzhhhvv\/wJ7NiEb6xk2TUr2+gvNq64v5SXWM6aCBS7UPBdCpXxsju\/h7nQc80pn7zxAJM8IYZmm1oFJE6CWvhEd5kP9bCT+jB5PKxPXanuVd2p8xYKCkJCllAaQlYZSaz10JkdBsefh0BL\/XS+VZMmQ7BJ+fbBtVhez1DvpuMIN12zJA+p4M5qKfQXmLirgfi9cZZIR7jvwmaioGaEUZ5QuDTD2jRpdyigd4ZgILJymSunUzKi3A6dr\/s8MXc88Ff2Nl6Bfu0uQdxQp9wZYiCPf5HWHLO9x8yPgA4h0X7juDGFD6ADIjm1NKXNLx0PzWGynohhZxVAqBMl95ri3qNEY\/rjRIdF796NZkN9a\/uVyHmPbfrYiel0lB61AxJJfaFZoKsqr+nsXUP9AJ\/lrjZg\/jOYb79m8KS0vC\/YjPUYo30njyBXIJUCdjwoFwEB8ox0ZezrjCV2HRx2V4jBcz5lz0+2Tf1cuCwOhl+Uak8Do9UeIhb\/eRItNWVDfsqq8isHTY4JsnohbJmme0h3jnClQZazdXHGOGAjKzY\/lvCmRYXdgi3wH1WEY0pDNJYI1mdi5C01sMdH38YQYsKDFDtHG2S9xUA42cMVo+9UO8CfPdcoGYwr4wE4CwFhuyrZhYtDjqSiKWRBI9gRJIRf0wm4SMMzsxMPpFT7UWqlkrdq5QtlS2HAib\/lhvWXczAl7xBWvKGDfCw4rfzVUVrt+BCYnJdSuK0dKKALWfM9o2IJPCTWz72ZSJE8z7IjyMVldqzKe++toU2RfHr\/h5gQ4+8RdoT\/Phw7AtpsKdjOOvzCRNb\/2bHhl4h8\/7MyLTnhR1uH5rBmljDHFYuiti0gJdjI3MUbIwqjEcvdOI\/iS1ASBvqoRlNM6SELQq3WcDX2DtTM+hqOaYrzodHHihE\/IhTX3p8IWL9yVNriyVM\/CHy+P1hSLC5PN+rfldbR+pZqYCxbOpKMpllBy55EiE1WaPqh1QHQLv9Sdc+UK7JrFWaIqvUQ1iBzQH0Z7v94mz98c07iNuY+3EkbKLN8Kb3Zn3hZKgfU9yL1UZ1YBZNQ3NETDsLHINXsbd6gRkeYE15FJ1lZd1PGDAYtxzbBiNFjfQQHpcSzpxXE\/i31d9GzfMMnQXW2GUjItncZZU1rAsIiAsgc4eK1qk4mmgOWNFf9t1SW6eO8v01rk+10ZH4tGXkxVQXaaFuvI8ScIkAR24VhUNxaER8kD3J\/LVqsLq7MgYBE6hG9mNkCFvV2GI00FSM58yHyA+lkCGM8u7ishhcwFzT7ofJf\/oapZ2hrx+MFhJm9eLWQqbh9tLavwLK3OJTLIl+zU2vAXtT7IdRTL0GZJdZceTUNnHTc\/Gh0ppuknBcBE6uOGCjAlvDkyvus7yOnNGIlnfcHYoOE4NIhzAitzMPcRDhUKbX4OnWDbbKNy8ahflBn+Cz0ukh7\/lHKLUlqd3kolM1Z3+JRdEHSmVWz7zWwbMS8aoyTOLUN2FZV+dzFvJdreXYb10UBgFVj9HoNxZBxkingWrp0ySCrT\/J0Yds9+MkIVm5xKEoUvYALYwpZhkI2\/k8R45GyqV3I7joo9pylWYE1VsuMs9tJAsUqtikpGeMaJ6b91KLE3VBRdFH+CiwOlnBduUWpuP7be5jY0dknYADCfoKg0JL0yd5S5am0oEYuy8rkLNxW5++U9oufs18ku6QTira7ed\/f96swaj8bIAZcLX8SRcIkZAnQkMW6qYTG8cFIFd3nBwPVufICvqhgQ5zRAuS3RVIRYv79A1YT1vBrn6ZMP16lqU69XJkO+otJ53W1XhKP6d1IsP8peH2h1HlRkI3CUwPbNhOd6ZpRXCaoEPbzjG6z1zFID6fFKt7fPQEfQdVkaOuz9O7BCb\/0TL7ByQAivNuCKDo2Seh7wHdAJlok3byYQ0fn9V46jWc3nWE5NwncyGD6ZmHryJhpWaRmDgCr8wgtHVmG+\/Xdw0XizzN13DEKCdVtCtPKCx7Xag5dTJpP8ISuX+4wo7zq1NgH0PT4u+DFvua0dSjKwBtoh2KTLAiOWBzo6tb3OYS11W6el5fRPqAWKSz\/UPnugqhEYxCsoNcWQ3h3bqK+PSo3WMlAcgKum2n\/\/Vd\/PyKqTuxvhn5Rs9mAKSIygEZEYKXl1zKGHuDkk9q6+mThUtKf5pM10nFV+Tyt2+vifjUA3eGPHX4irwKoQGmPW5LsW2fHzKJC7BGMO9os0SpXTWpBa\/f6YFVVY\/cGl0wLm521rbyNEeb7w5rhoz1nmHx05eBsjv0TSZzwVNdma\/dNRYJdReo6jixg0XXrFpi9kiqXk\/4vlBHwj9kzIIXZi+GvzllSLgSllZhhQC7341y07IqkZb5h\/WjmkOdGHJvf329XrRe8mlLtneNWafX4sX9V2sD0En1nowErzcthouWRLDK8Q\/SkW\/m3cv5HVoDh4txGZzjQ9nOhVnme1BN1HNJnsUnBp7ZhdykggY7U\/2556lgc+\/Vd6oLxoic9r\/cheW91P6AK9YLR3uQYiOhXdD43MZTN1253Ge+i3g34TQuTs\/5dn\/j5SXmUWi4qmM1QJt8c+yZgu3hIz3fPr0tlLXUKcdS\/osK+YdmI71XkoTP3IKnEpxn6mpUwo2TESlgtc4BUKvRuN9PhWRnDoZIRexVb6hPD7e8oROW1k7YfXbrGsD0HlJ96Rc+S3q5wAMuObCldJfnc4zbGqOuWpMc\/pwL4T6sZm0ZEg6HFCjdaF9tiyU6nG8Az4cy0DbWbrIVj4uB0MphQA77xUopW46iBRIz\/dLRteuABzej8xBBRZWDWz\/W7HsJxwLWYxwL\/hQMew\/I2eezehArrJJKel6KnhbUFw\/E2CWKDGw89S3mfnVWjtujZkmsqIJsUcoXSqsekBXsBoxZXssT55AJSwAY7yBB6KAG5UrA3RQQf\/mGzwzMCtVVFsXiTrh205KPKxcCylIGzCZBaNZJB3eUk903Dt4iPr3rAEX\/DpqO3LeI4dZARGOvjqYye4HrFbMc\/\/Y170w2moebNClAw\/ubKaTk14kg4fSBiyZygDz+Myde0Rd+2GVcxYTieHownEX2iyqm8iwyMWW9G3wVl4gWH8Bpl6qbZWJu\/Ciqq5JkkVtY2fhkuoAtvP6tk0nEZzq1shEBtILk8dSR7\/FdZiQxlSC3VH173P0wGjMp0LyGnP7ZdhYYjgdXkf+odBxqrZ0ovblIU0A60JtkI73G60SucZ0hz9mwIUzvxUnxoyAOz+grqdZNHNO4snnqV0LKIcuK\/Li\/OJKWTvFF1DkkawerN1V5S5g6zg76a8bVe1gjZqckJz\/ru241QGN1K7k24Lnin0LVZHe+nIDeFkvg3Ecsvk5cTpNM8LEqKquDOgbPtowABRGn7QBeuFksGO++7ruucZ7v5Zf3wkAG9ZFN2ZsJe1Yq0dmmuj71e0JJm1yCjBL3nYRK0xNV4PdM9Pl\/+vXfJLA4KONs5lV59AfsJj\/diWX26fL1UcjDJJxKkeN+VjyNrqgJGnf9eyyXfPDC1MGCejogvbazFyCRecOBVZwYKScZdmXORBAcDtw1LShlllR7PyHK05a84AQsft2Bbjtjah1apm9oMoju8h+gWAb3AW9\/Db9djzengrkVt4My5TASLy9e+snZJ8bSaG5MfFQx2ECxzQgsdf04lWjXh8JKlptSNkbXy9MWKS37Tu3m87jW6GF8Kl4Jam5Z++Y+9r\/mZuqHFIqo3EiJhrynPa085+AH3WN79ooft8tfWA\/NV9R\/Sq7mcDgmo5fQtt5E0C\/6YQ4c0eOHh+n99gy2JHr+mn13ckkhyrFa5frUYwkV9vDTakH35t6A5qdlGzPPxwvh4fpB1yJhdLlf3PNV2FRlrzpwzujAngB28IsrbJLTKrcoBmUfVSbk2PzYiZ90Hwu\/6TDui0GJ\/GclAXWmwY8g8vq3bBWx9DHEk61rUPurwxX61DYFJZX6FcYfjqFgd\/CXF3h2ffzqE+\/oEBEkHLujmlZHCqpYfFya6KOsvfIiXemFLP8S1WhMTmE5\/qBIY1Z4jXDDsQ+j7ar+6aTwpHjN1dWwoWjkS\/tMDp5bzTSyFmJi8\/ECHrGeMVzdbEAS1WbiY0CA16308+O9GGuUmudoIUgx9JaE23J3GYl9PQtq9RIqYWQQK984RQIYBWrSxv5C2xkVJ8Ino0XaMYiMd1lUsC9yr+g+51NOt32Gdcn8BEq7IPUmFs\/n+0xLFev2zC1\/ep0WiRCPN8X9VizxGEjFSMQVlD+5MogZMPJCXE1Rkvli7rTbh02LBS+2qoRHJhWA4Q5+2ZB\/F7TAqHAnUrHC86ZqfZnXpVdd+VKopvedVqIFZ7fE\/sxwXZPr4RCg4+pipTxS0ALMaErrl6t\/+qkRJHHJgFYAicf+eFLS5CyYePbCBnA5lt4cP4mxqBzP1ppYRAnq4N4kdqo9XPjM9xrV3KEbZlOKuvOi0cLJVENmmNIqcChofghadS2QrJ2oBCJlR7wCLflLyMmx24a2dTBN3d5Yfu+DJERzrK36fAPlAgM1g8tjH5phKY+2x2IreVsRtBh5Kg0aG\/WAYmWtHSH62JvqarF3nepebe7XZWBF2jZzpNQ1GMmObC+BuBijUSvqZc2QAk0C2zOtYXzgmg7DQEscmzF3exf4nSC0i+NgNRqsSLKD2jzjhBQXmDlVghpQC\/9l71YkzHJrW6gVYKT8MscePcRlOgmVvftD4ZJ4X8qEAwWwtdTCYb44Mb7OmoDjwPicrw3SJFGc5s18RAj0nz\/3YeteH0Z\/t0HPFRivSYh4pdvbb7emGvH3Zid4XMtaNqfa7zsBY3su8uxr7KOyiG66zB4qZbA0Plb10zpeMpIpkYyKos\/D8xY520QXaKCK9uGFh6ho1E6WzsRNzWzUTFaCe74CVTp\/Me4c9Xcwsqu3AxVm4nMvaKr7QSc9xmAnHZNXPz4wH556PtbUkGx5s212WWYQJiZgwEHxaHHEm1j3\/Td7qI6+lvcUl2SvYt5M\/5zCd9uv0AC0PnhnAN6Qkb4CjqQOrnGnwdtgG8lyQcuIfmzQ++mH356Pukqd+PthJnurnskcpeeiz0nsYqi5el0k8emlqGAui9M8dGUJiX\/ObunM6BNImno5VJTjVmnub8nIKVn6\/RvoaJpWAmX3F5UuqaIAAJqoVIESTxnH\/ap2QqHmTQarlAdWWDr3xjyg9v5XtCP71SGpnSuYjJDJ8a2mAOywQ\/CAbKeOTZdnzEFG9ZqMdf4zvN\/D4055qw6hmOqoCwSBSZpQ54nOBLxZGYPOaSOc111e1tjtywlCZRvr5pJ4+XXbWwp7\/h7I27uxgXEWdkc1PaT5qe2i1cr4oIC0zvhQbpwT3mRCGOUAEHuOCQXCfOYKpDs5YKgS8ce6SqNS\/0b7Mpyym0bWDapXXfBfAJy\/t1Qp01LvtaHXCQrBifzvsc1sK2pTJL3SNb7hLoXosLFBSOsoLSNMnpX9P3sNGApgBlSrHNL\/OdmktIJKTNDVUmumclPIYL7ja1sCGO7BUc2vIlu6JcMU3b9PIo8F5SIYXEg9wv47uZVoKrcRgQUhWovlzygeiC\/2afSOEOLzZaUozcup0OLPyc65N6aT747HbadWv9mpoOAP0Dg2GAlnF2JLi8UqIzZSerqwYfZgR8pOygtYdEBYdciGlUAOcRbbf04HPXqgju6Al6wokx8Ldgez5LAGRWeKnU+rxRhVEI4AEXOx+2ziRDPkGgqr3A91+tq5y57RoJ05se1J+oXkfxIPv85nDWPr+O6PoBuwO2AZw7bjpCBjUA\/Hyo04JK5L6BGpRIBvs95og8bwbuE7kHqsW\/EhEzQTJrsZti3AQU+PaLFD42YP8mkfCmmNuCI3cYD4MCZ\/KobwTb3Fn37Aua1cZ7n+28faa7DZ6vXZcigcZr1uaOIujnfr7Ok6QU0tDHtDzU0a4ISgxhtvCm18VpNqst3WVq2OFNQGNLD6wvoSbaFrrRfhfOI3+I4YQMsdquW7YQ1Gx+e5DWrp9tKNMKK85lABBnHlfHAExrouWHjLyKENXF5ooSCDxjpTEJEME9GmcVLG8givKzhJJnWQ7Ojd4hdTMt8LEUP9ad574khbZVHmaQgJ\/bLrvXH8UGj+uHkc++t7wxNgD7hFEvW7N3gQCXCzJYoqfOGxqrb\/diLWzMlLoFFpW\/P1oSIJjG5J2pX+jGBnl6OMmX7lqCBG8tg\/rRmy3e\/GZzyxQCaMQ8WpReCicvGCyUukQZOk5ZzZUfLb9GA4DuYNSFYNbdb48Sj4\/JQre2tr3Wy6EoxyaWiLAF3hjLfnty9mZJSLRWW60JLQeaO+abFVrDyftdFHgqhFoTPWsF8\/JgC3tSIrNUkYBzqlPVEtbhKB5E3lg1aW4t8QLtq3gfYyOVpin0gfBkBysQfLsVSUnQLZ6Jcv9Ko0U+3AUOFQtJ0l658r+DB3N97ayjFaG4pCHj+lf7+NTXlNziY\/ZRdHEn\/SG+MEApVqGMdpgqYH7foUA32Jv6j2M4oaD52uc5AIfVQlc+gf78OvaQAFCt4TgaA2bE5EOlcfWn6\/cZokOOIIYb1tAvyZ+qCJ\/ihqqwZAg+1qUYeebIFNevCNqtKWCQayrSAZ+FzlDUeNrJMQ2AVcENcXEMM4+IxFNvUSX+5YcvKNzhUeFeJG9Vgk9fxfa+s+Z9ft2ZZsNx+hfAmYwNiNPqpTIscGiqJNDcsNymoTE6\/w3kcmiURUEhWEHIhQMPL1Jny3BFfw\/NqwKcrZ6qhiGCrP20iwGJHsnJRb+ZbcuYGHrODtU\/uupah3TLskbOJojIMGuclz\/rmz8RWyrvY9o6rLdXd2PpBuV5+\/e8wPeGQJ4APyDD37Hjw7Hr36mqJqe3AhXLCxr6r7+3TwRg1Gy1eL7ToLw8uoIZevn7YRwXZlJms5FJKChrR6a7kjTPl8hblxLjq4m+i5iDJQZ+IvnRROkgxNQzHekJx4vHbIUxbJe0sUJsljYU+Y\/Vg8Esuq2kSDy2H3xhpmGc1fuQEag9Y6IOH9zAU9RtmkSt3dOGvykaBZzBYCpiGRqTUNR1yxqIj5MPLCRtluJ7O8SPne4tVnpScHEL3o6DM2YXJP0oYzdHr\/FIG+1JdPsi5GkyN6TXDJFKzDHBWFG6FLwM\/RaBdBJSC\/6IyBNjy5AAmV+Uf375RgEDpzEGYcwfLVywuCr8Hj2hEHJ6Uk6Jlx5tCL4H4z+MuByxLVyhkYMy4Xlyegwo7j\/ss=","iv":"07e6cf393216d777f6659f2b029a0848","s":"ecd93d4b3d7ea04b"}

Sophie Theallet's yellow-and-black floral print design for a fabric that was incorporated into her ST Collection and registered with the United States Copyright Office. Image credit: Sophie Theallet

Sophie Theallet's yellow-and-black floral print design for a fabric that was incorporated into her ST Collection and registered with the United States Copyright Office. Image credit: Sophie Theallet

Sophie Theallet dress compared to the H&M jumpsuit. Image credits: Sophie Theallet, H&M

Sophie Theallet dress compared to the H&M jumpsuit. Image credits: Sophie Theallet, H&M Milton Springut is a partner at Springut Law PC

Milton Springut is a partner at Springut Law PC