By Milton Springut

In a prior column, we discussed Forever 21’s lawsuit against Gucci, seeking to cancel Gucci’s registrations for its Blue-Red-Blue and Green-Red-Green striped marks, and for a declaration that its clothing and accessory products that incorporate similar striping are not infringing.

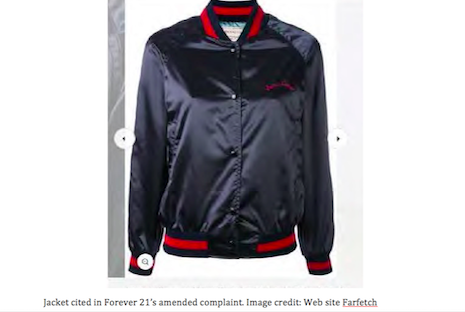

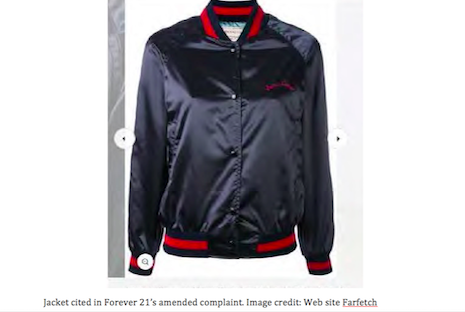

In response to a dismissal by the court, Forever 21 filed a massive, 145-page amended complaint. The complaint mostly repeats the same allegations, but now also includes more than 100 pictured examples of products sold by other brands and retailers, including Nordstrom, Bloomingdale’s, Tory Burch, J.Crew, Louis Vuitton, and Balenciaga.

Forever 21’s argument is that these striped designs are not perceived as trademarks, but are merely decorative elements used by numerous brands across a wide range of price points.

While it remains to be seen how strong Forever 21’s proofs are, this argument raises an important point for trademark owners.

As we discussed in our earlier article, a trademark is merely the right to use a particular word or symbol to identify the source of goods. It is only infringed when used in a way that confuses or deceives consumers. Consumer perception is thus paramount – what do consumers think when they see the mark on the trademark owner’s own product? Are they confused when they see a similar mark on the accused infringer’s product?

Since consumer perception can change over time, so can trademark rights. The bane of every trademark owner is “genericide” – when a mark is used by the public to identify the generic product rather than a particular brand. A very famous example is ASPIRIN – once a brand name, it lost its trademark status when the public used it as a generic shorthand for acetylsalicylic acid.

Less extreme, but still potentially deadly for a trademark, is the loss of trademark strength.

If 40 other brands or retailers use the same striped designs as Gucci on their clothing and accessory items, it then becomes problematic whether the public perceives that design as unique to Gucci and identifies an item as a “Gucci” item. At best, Gucci would be left with a very weak mark – and competing products would then likely not confuse anyone.

As a practical matter, this means that a trademark owner has to police the market to stop infringements.

Tolerating other uses of the same mark weakens the mark’s strength, and in extreme cases can even be deemed abandonment of the mark. This is especially true for marks that consist of product designs or design elements – which consumers do not necessarily think of as trademarks, and hence require built up commercial strength before they can be protected.

“ENFORCE IT OR LOSE IT” is the takeaway here. Trademark owners who wish to keep their rights in their marks need to vigilantly police the market and make sure that their marks do not lose their source-identifying power through widespread use.

Gucci jacket with blue-red-blue stripe

Gucci jacket with blue-red-blue stripe

Jacket cited in Forever 21’s amended complaint. Image credit Web site Farfetch

Jacket cited in Forever 21’s amended complaint. Image credit Web site Farfetch

Tommy Hilfiger jacket, cited in Forever 21’s amended complaint

Tommy Hilfiger jacket, cited in Forever 21’s amended complaint

Milton Springut is a partner at Springut Law PC, New York. Reach him at [email protected].

Full disclosure: Mr. Springut formerly represented Gucci in unrelated cases.

{"ct":"G\/VhFO2FOvOVbInJKENvMHmR+ueMm\/ZWu1tutAHtzpsYFwXMtb+zb61ABtvUghN2yJhjIFcq18KUPgXejO2ZQ0juQ2+KCwcsFnJcnx\/JN90jmV3YtCrtFcrB2IWcw6qjh5XWbticrlY1HsLvMmoULEK99P2khb4CDU9L8vJmEVNeoLLBLlumu7vs6oluyKjAb4WgqOaetFv39xKQlkOmTfbkkSXyHTDwTwuLj5cTj29wT6\/EZ8LwIA8w+QEneFgjwmZN8Dq6kToluJHnS0G0iTCmUbXPjfh+qHf3uKOBRe\/HYUFB0S\/m6bn2JJd6KQuCI56rGJ\/1F3Do2zcrZKO7j8K\/qouAVe3i71mQ+Rz77zL5OiKH\/zvlbk3VdtHfvdpdt3uU\/2\/m\/9mbtU5cTjrRtyJ6McA65t77oDDF7qPT9njb4RpMpVncBKxwijLjJnOXmoYbk1QkxfkRnKuNIuGSmzB1QqSFr1gejACYO8M9yot4R0i0pIDe0DMV67YECfPQGA7tFLGFsSRwpZQfGHpj0GpftAQtVSfaGsXDKxqIQ9jvlxhqS5pBnk+cjRtpv\/tlrOdYq0QN8aCS9OgA2pil3anbcuc1TLd3TRjEnEbTjnRFZpme\/Uetro953vQMOhoimszSEipUakzCty5SSrXWj1O8v3WkbnRccFWIzbVeekluVADcJ3rnNX4PAHw4g0bylJRDmBdMc4EaDjVAkN34+m7df0b2lrQq8OfGqp7WKDiUWyyySPjSUPkhjfhCZdVNJsL\/QNn5Gf9fJmI2WzlZXKlc63UclvsTsXz6Up+T8kNu85HYKTu3qXtoYZkcxeQijnPiD80B507b3ZvPUCJjG+CyyNUrUJ0OTioltPuKjLB4W9P7oayJhvY8sj9fEBRg4cHXV5oYHtX0G44CbaGiewdnc9nG8ioNdCxRinuJxYD0rdzdXPF5HmXVbwmax8NC5dHMM+8rJmkgkl0Uqvn2otyKeGx+rLfEPgU\/MuWOQ1pEaxh04Sm7qkP1E56jCcCLFXYs285x8X\/Hok7JRqTbYSio0yYna8a1Q+8wYUf4G1\/rCp8W4602EFbto5TrTUl6e4ofZEEeNZ7tNvuBtm+Vly9APSoapyPXMncYm21cLh4GsCT17wtT+uIyQZ+NixkNEOQPjWcW0z4recXFG743MF1ZV\/XwHqcA8mP6hXQZrE60njO1Oivq52knuua6mb5tkJdQj+fwLWC+5Yzj43Uv4XPkTAaYntdlZwD1ejZBb7W+2xOCUumDO4mnWgmeNJQaP2s4r9L7dEf8oyS1xl2Xrc5d3RCi\/MWBCeKS08CZSfyLEJv3FLaGPf2V8MOy1gJJqxaS8tUconI9uUopLHxidnwoPFlxd0VcU+wBAVALMDsdn8zGki0L36id1wtYipqtX7917+c2uqxCeOuzebvkriL5SXMe75IyaEt\/qVGfPVthSbdMV0ua+fqp7u\/iWy+nJv3oZYf22H3s8U7VcYJ6XWu4JHRUET2dfHZuVfqWHffHY32wWlEAF5lgd5AXzFyf6VIEg\/Jjssgrnk1Q+5f1s+topigg6lCR0Ww3\/81qMFYy7EQWFKlQmD0Qg17TSW+BSqq+YjyiJ4Ytxx+yqcL8FfBUsOxdzN0VkKgfvwC2H420AmluiRfgbiRE8I2qaZMNmm36e1Od8Lre\/8FOClPupy\/1Ck9yDKbonaMQ4dStR+7GV46Nju2FZpu+y2vQyS\/BxwRAa2bRuKa9kgI1jhPxAfeHwJ49FVYYnEa8MJFAwEM1qklWMugL5FtwBcFqnMQW+mdyDoXhuyKdXe+HzsLCSjCjPdLX7BITKrR3QBcFMVojL4d8gfLjDeGCFnq5qyDCT0aahi+YJ9I9f8+y+MyGAZj7oJiJJNP0YL+5jwOacrrfXBtyeimir9q2aMctRg8mQYWFpPFkQ3JkqJW7hsAUkFmtEa0N9fBXqdGRz2rxx0VwZSBey6O+XD95ulcOI4CahvwXbTo3URkC+gjOkZScBr+gG9HDtAX3reaKsCxINF1UIDMROTcVikemUduURCw95FLf2KQkmib4siFyJH0lz+7740O32c1IjXPIVBEu15Ib7Cx4Jy2+CIIN\/vWCf0NV4J8apFLgwB5gJjG1UmnBOH4\/cDU7W6Ih7Fqyj4vzXNZXQjl7nmA\/Bt+DTqgw\/yZf1vdWocxNnFw2JKjCtfadXOIcZf2sDRmqY1Uk3OfJV2jf9w16NxOrx1Db70BIxKaJdSsf\/ymJT7lsdffY5iIdAzhHiplOdP2B5gi7vTIXjogkPADQGy\/raN3yKhQRZvJV6c4EkWA9OR+OgYj2EaeOZm7K72dCGCy0+BtJ+6aDsk2cSp1FV8vP5D9PU1s6Qp9pTxfkOxhtPOxwazhKPWgN+88h85LuOW7Y4ezN8OVkEt9d9OrEW9vjHn8vVMwHSGMU2yKrCmjUgV8hT8hMc5Ql+ig4ZTU2WvRFJMdNTS+IVGNtJuNvcH9siBJb\/Y3AKGAltttZVg4uO9CVXsYKFEOqXvLNXqYeEGIRihMInSbA6xBeh90ffavEYTidxXAgJe97mZYCwSrTy6h4aM6D01J+WUT7atj8qMSniG66b3ARBOmv6lW34wuNkbs8S\/QwRrcgGU6AV92HAYYhMAsCQx0ctQVIusNw6v0Gspjgus8071VBjIACD\/JL7uMpMU6lW6ATL0LTypv0+5aTltjvoz0utEpOaDhFC+F8fL0JoHlcWO3tcgailTRLppFxIsY0YOmChzz5PTpAaYo3zCpmhg1gb0XcRp2uuP6c1V822bLznWdw4S6nHgqkpTqABY6BytbLITJi71jYwGBBH1+kKoJMnvmboBlMPfCKyrNKCvPNMykmckkBSTnd7MMvdL3j0HOcJ\/WodYHm3ktOWhFkwG\/XR6AgV+Sl9oJPZ4gv9BS4XlsHpfimMDGAeVE3a60yOJqhxKAge8lcrMaTrXNR5Nn3JbI83Uc\/z\/u8CGR3B6XV2LUvmSH3qaPkugQiGJX96uq7XPPBvFhlOMkA7dn82gsUXhWnmTezz0Ih5XNntJWmyXpjkx5JMGS8\/6vwLCre6e9CU0deeT5J\/M+JxGUsWk7csibGQ6sqxUqA730mLlcdo0iaPN4eN3o5wvF7KoyJEBn5qCSX9feFtKXfM5ZJ5jWEtFoVjFnSxsYkkQ34Kis7OoR27vSVZDLe4YXwSIYfoflLiMsr6K\/al15a8nsoijr07tG9YxBXEIkDlteMwMHS3J7z6rbIq0xdN2fFY2ltPp\/\/YDPnttzws8EU5skeSHUPYHPGsMLGvqX2O+tH1RDQ2gncMTKxjLCs1lfJti55GoDH7QMTf8ACepZ5RLwLPet08Q2B4AEpBsUGC6TEbOSmFmrCURbNjz8OkPUYGsNOlIj3Y\/8zfDtx3yoztQrvsDQqmADFLwKD\/M7UtM5zqmpwV5UP4QLLOaIPCKmuiDf1vycym3L0aijZVHPLWsAyYtUraKMFhds8YarzZkabQ0aHCGkvjy2Uv\/Dv8fv0fshpQ+\/N+vb26RdKABnpz3UNiUMsqmUSbXkidm1uOX3eOKTi0maSlpqxP0EvoraSg+jBQxHev\/x9tqpiZBt535v2u7z4iqN8FBAV+mHPsL6VZQfkIf1n\/vAz2hFx8wbYsXYPXoJlPVH6yrvkHVBgYceyEcQA1UYCg9\/pxdsXfO+OJetGk3e0PcYb9tZ9W2B5fuQw3QWCG71QGL18eVPSJj2fgXP6z9luIll7R4GTbwwtNoZyaWCxdnVSBxOpmjYMpVmWr\/8V2Jh+bFs9+g7Ip+9glhCApcwE5KmT2BZ2BbmnDWTOBwdBQCKNbL5Rje\/LHMxrj9jJOVVqO1GrdT5oiw0UlUEDo9TZ1Jnm4uTmnHvkm26l6LsTdd8DY7vVVBuJY\/+UmXMcsM6Y9wlu6eXzm7bQYmCJhn7miS41J54oUDKD7vHVqCT+Y6WxhW3roMDD9Mk0oEUHF\/jNp1SMHFO3HuzDmTp2VhQXqHXcAgruK\/vKczLL74LLMhma0jSKtXuTCt+deMpjhjLNDjvDUK73l+JOXhZoiGId2pJpSGZ77PCzMK3mP6nNWvXcZS9YFIBMQ4hGD8xm+8o\/3RDYj7Z5ZfxjUinLhziasXgiyFwFB9DRabmvagsLocuSHWpq\/nrC11GKUa00iVo1SbhtAIQp+Ff2TP9vwYxlMjZbfC9t3rFtTH\/iJ3B1\/GPhbjhQ7mDOG6FOhHnxBzHkMTcAQ81ma9vTUrfC\/y8jF8a\/zvsN\/yUQcvGuzcDZZXFtsVfLj40WVPdkt1pzzdUGcoSpyWK9lHe3TFOMAeJg0vPECuzelCv2gnUldcwFA+6+L4DaRAZ\/rPxanEytHWxRpcgriSn0kVi3tzD98mwirpPjzS5PGe3bErxInYcAKNuZEvrWWjaZOpg7Q5uahsLlS6TF08xk0a9lDsA+QHIcoNljiMY9t7LxogPMmLJmm3Az1WqRhFxksMENCynrWu4Ff4YMtJGFl1tdGBT7JRCsA72MYTKyr6h8djYTdp1\/6hXx+uSG9F1AQRdEgb4cGM3pXVAX2b603kFfdwuFVWqSIcUUZzM8Bxx6OYP4hBLoQdiz2pY2vkMTyU\/IfPDtjHET7fUDwmsRXEBfdxjo5P5+SS8R8VOPYw1cwG2p2rN+ibnIF733RlzHdbXa09xLcFJMMalDsJNebFbdR3\/GBLPKcpcfbUbgrHmIxLHv1Lr4tyTSu4gjW+AdLesc76Tb1drBusC6qrGFkD1OgDS9G\/uIYadJ\/R6H33EToNztVG0JoQ4YfBd9+cuBkQUYn5Gs\/XepzVhUubVnn3amU\/l0dNEIkBFd9JbHbwV19KGb9ZSFNW1P39GOawVeUKYi5PQJOT9g18XTA9qQ5cLVAeNhtl15H\/uQ8KGpukSjXaiIjRNR5P7P12YFR23mfAELDKseti4wV1qABaRx8TzdGDS2zUhKg7iDHFcBVk01Dz8F5dhTvWRzOScUInwX7boVYDac0oJ2FZ3WNmBRPvZhlT+lndX2JzU94lWfIQkASqKfjxHPxjN23Zc8VhM9sDIVql\/EeheRgD3X5vEMh\/g7HCainG9qx1ykXvFZUEI0ei60RTz5XTAG+iz3hS6S5+GcalsGKosHRPg7r7fyEL5xGzcRG6tteeqyhaz6XlfD11raBxmSiEuByoqsNnR1dBSjSem6DQxrBEqtzTf5WjKuAVyXvJ0Q3zcJOmqz+zlupe9evoQJfxGYuF1OS54go4Ym74MKtqSqWEY\/vqfBheClBEBh4cWl7YGs4zVexiBGpHiB6J\/mt+Lt7zX0aVZSYiijLAYZZFhJKXRo\/w8qQJHVINvoUQOxdv1GuRIEqJIClgDaUvIe0nva1AmFMp0GxFSoLRzmg\/LNzUa+vwPB70KiJP2OZzPU56pzUvZenECQZ8zXFC86D89KB38zi\/41RjaHsHxyW9Ht3qR+x42sIeH7Zy5+xxf4+6D4z+GwJoGYHkj1byJigbeb3VYhYUQSynIcgBH06\/Bs1YCrXU8ifmi6IAXz2wWSwfaprzsrFQAnm3EyKSQwa\/tLfK9U0OsFEZoWR1CeP\/C3gf8oxGVTN7DFKclV+VH4eVckENQb4YYyQovKvXnUr\/dRPgFJx26EgfT1XAbTr0DXdbDtiRsxJRQEK\/N55oWm7l0VvLDa3FhKZsAbqp8Wn1HskzZf+e7TGzN8RPd9E+spniwgsja+gpscwRnR4scsPB4IpcXXf5oO68gir687hdOJauiR8aDGqLPUlKEfvXeSF6m5YTzvZcGwPejVpFRzdTNwyhruwdtPhV9Mwy4pNpiM8VM\/n+yDAZnV7FxEI\/ubQ9ZnlxDWScbyJ6nRcVz1FSFAQEX+4a89iTBsOLKRayinc31BY4vN7hb\/pke8U+YwB4JvKcT2ZbfR3p4HF0Elghc1PX8nbHDy0QQMLDFi\/SSju93llXsTy48OIFlkMED7f0yDVIfCyebHB6LQuMfhz51yl6+BjtMJGrDfyBmnrl6kzcfnM\/YiEFEpAxUAlLr7qlut29othfThMycjoja5310U4Ncq5rf+Ii5XLaf3Yd9vTgCmO38TPDxX9AZfkT5i+GInOfFgfxr6RldhbfBf6ZHS1UAsmoFmlfMmk+CrqvR3sNsIr0y3Ws9j0NzQxH7Fg6UKyZ9sWxn9\/p\/\/m6zPxr1lfdbQGESrk\/BdeGW+1nlI0qG5xeZJQ7lVWPj2oNUKFwCLj2FhDWIl9Ma4A1Tkl6hU5joM1COfTh5IUIGv5HzMgsJ8bZgHLRaIh3+jpHtrGW2Hso+vEBzW\/sPFabk59M7v8NRNgd7LjKPd23qJpB1kZpNA3ucsbBaMqffIfzTeBnTZB2qX+gB2jT2NKK1kS2\/d6nKc777qF30zqD7pq124WWJvaaXw0kXD+dTR4KYBvy6scspONV2UPxgR3RdNwECZXba\/2k+Ix4dmYgkZGw2vlUI7oToWltAUbS17+dyGovPrbGM5iNifIlxWi80nTrwB+VrCV8vgfW1cXshsSsmRzSnyUZhJRsuYJfMXvSup5c9lrloIlQKo7xGMIYUmwdTIv4L7UJQHZkOSNaJPa03s970tw8Lt6b9NWxZlfSPECntJwKaLIuKM6c06NQ==","iv":"95a41a50612329a69159f6725b09b5c5","s":"35bb0732b717e7b9"}

Milton Springut is a partner at Springut Law PC

Milton Springut is a partner at Springut Law PC

Gucci jacket with blue-red-blue stripe

Gucci jacket with blue-red-blue stripe Jacket cited in Forever 21’s amended complaint. Image credit Web site Farfetch

Jacket cited in Forever 21’s amended complaint. Image credit Web site Farfetch Tommy Hilfiger jacket, cited in Forever 21’s amended complaint

Tommy Hilfiger jacket, cited in Forever 21’s amended complaint